Part 1 Index: Etymological & Teutonic Sources

- Derivation of the Surname RAMSDALE

- Etymology

- Teutonic Sources

- Viking Influence

- Danish or Norwegian Origin ?

- Topographical and Toponymic (habitation) Surnames

- Heraldry

- Notes

- Møre og Romsdal, Norway

- Romsdal to Ramsdale

Part 2 Index: Locative Sources

- Ramsdale Hamlet, Fylingdale's Parish, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale & Ramsdell Chapelries, Hampshire

- Lilla Howe Bronze Age Barrow, North Yorkshire

- Cuerdale Hoard, Preston, Lancashire

- Wade's Causeway, North Yorkshire

Part 3 Index: Danish or Norwegian Origin

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (published sources)

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (table of place-names)

- Viking Society Web Publications

- Molde Wind Roses

- "On dalr and holmr in the place-names of Britain", Dr. Gillian Fellows-Jensen

- "The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire" (1979) A. H. Smith, Volume V

Part 4 Index: General

- Fylingdales: Geographical and Historical Information (1890), Transcript of the entry for the Post Office, Professions and Trades in Bulmer's Directory of 1890

- Fylingdales Parish: Victoria County History (1923) A History of the County of York North Riding Volume 2, Pages 534 to 537

- Ramsdale Mill, Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire - Postcard Views (circa 1917 to 1958)

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Edwardian Postcards (1901 to 1915)

- Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890)

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, Bronze Age Stone Circle, Fylingdales Moor, North Yorkshire

- Robin Hood's Bay - published articles regarding its origin

- Ramsdale Family Register - Home Page

- Whitby Jet - published articles [THIS PAGE]

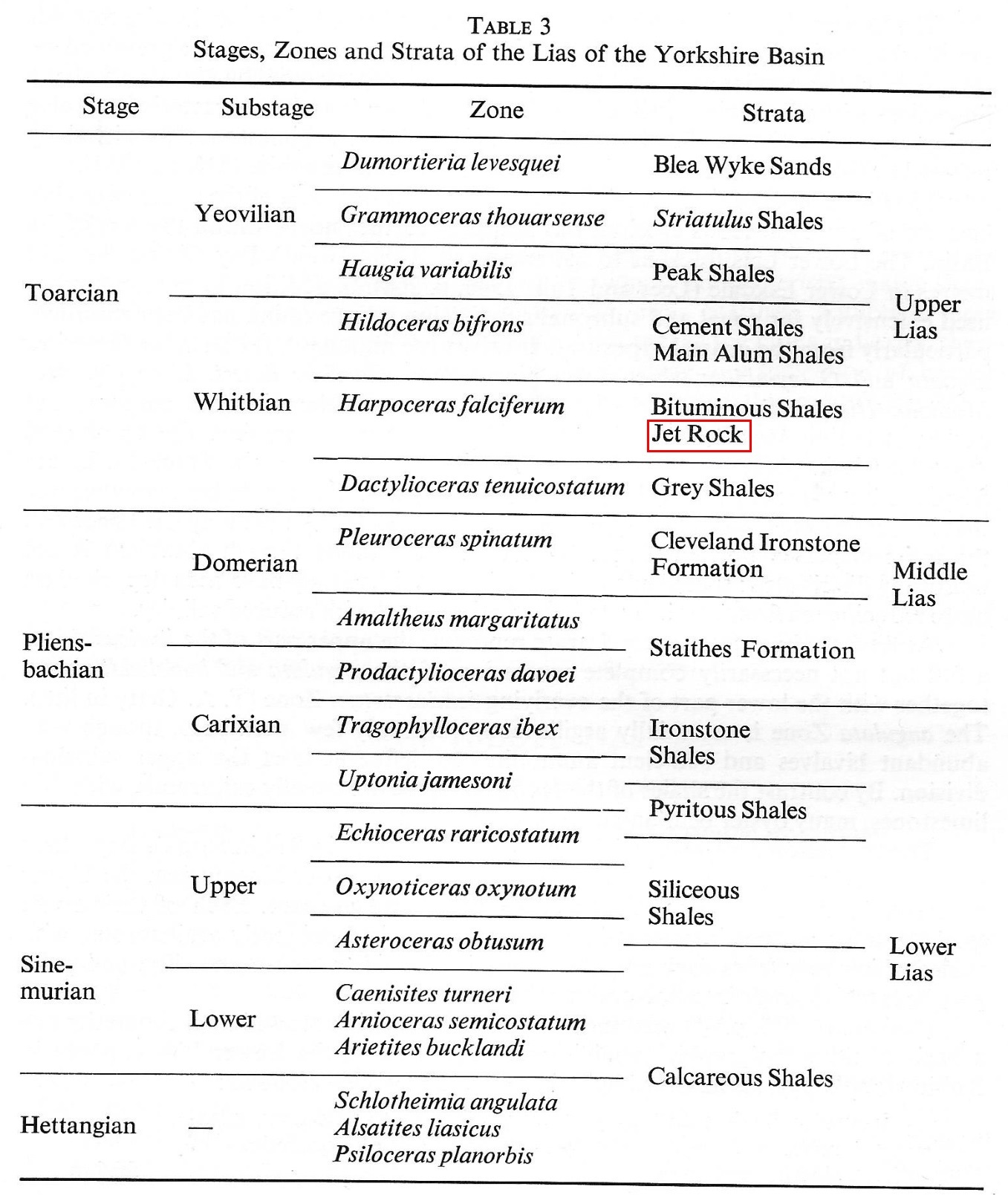

- "The Geology and Mineral Resources of Yorkshire" (1974) D.H. Rayner and J.E. Hemingway at pages 174, 175 and 181

- "On Jet Mining" (1881) Charles Parkin, North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers

- "Whitby Jet Jewels in the Victorian Age" (January 2013) Harvard Papers in Botany, Luís Mendonça de Carvalho, Francisca Maria Fernandes, Maria de Fátima Nunes, and João Brigola

- "The Story of Whitby Jet" (1936) Hugh P. Kendall at pages 6 to 12

Introduction

Jet is a product of high-pressure decomposition of wood from millions of years ago, commonly the wood of trees of the family Araucariaceae. Jet is found in two forms, hard and soft. Hard jet is the result of carbon compression and salt water; soft jet is the result of carbon compression and fresh water. The jet found at Whitby, in England, is of early Jurassic (Toarcian) age, approximately 182 million years old. Whitby Jet is the fossilized wood from species similar to the extant Chile pine or Monkey Puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana).

Jet has been used in Britain since the Neolithic period and continued in use in Britain through the Bronze Age where it was used for necklace beads. During the Iron Age jet went out of fashion until the early-3rd century AD in Roman Britain. The end of Roman Britain marked the end of jet's ancient popularity, despite sporadic use in the Anglo-Saxon and Viking periods and the later Medieval period. Jet regained popularity with a massive resurgence during the Victorian era.

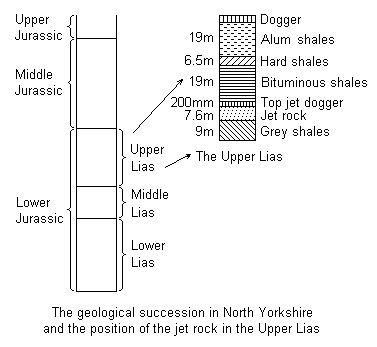

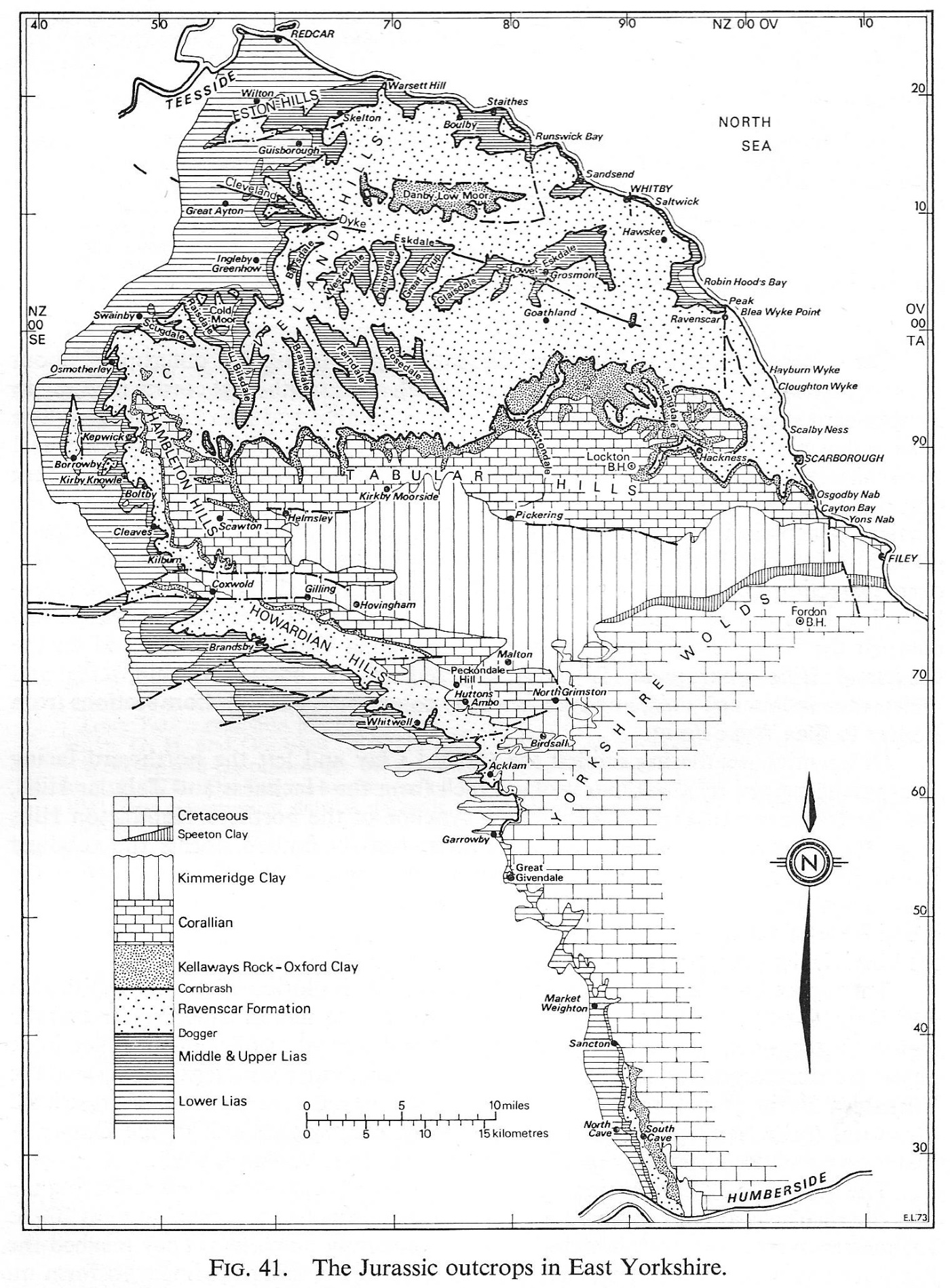

Jet is not found in regular seams, but is randomly distributed throughout Upper Lias shales known as the Jet Rock. This is up to thirty feet thick and lies above the ironstone strata and below a freestone called the Top Jet Dogger. The Jet Rock outcrops on the coast from Ravenscar to Saltburn, on the northern escarpment of the Cleveland Hills and in the valleys. Drifts were driven at its base to the point where the shale became tougher. Known as the 'face', this was seldom further than 330 feet in. One man drove the drift, using a fine-pointed pick, while a second barrowed the shale to the surface where a third sorted it to find pieces of jet ranging up to five inches in thickness and six feet in length. By pulling down the drift roof, to form a platform, it was possible to work upwards through the shale until the overlying Top Jet Dogger was reached. This took very little timber, used no explosive and relied on natural ventilation. The work was lit by candles.

"An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language" (1898) Walter William Skeat at page 308

JET (2), a black mineral, used for ornaments. (French from Latin from Greek) 'His bill was blak, and as the jet it shon'; Chaucer, Canterbury Tales 14867. O.F. jet, jaet, gayet, gagate, 'jet'; "A French and English Dictionary" (1660) Randle Cotgrave from Latin gagatem, accusative of gagates, jet (whence the forms gagate, gayet, jaet, jet in successive order of development); see Trevisa, ii. 17, where the Latin has gagates, Trevisa has gagates, and the later English version has iette. Described in Pliny, xxxvi. 19. from the Greek γαγάτηϛ, jet; so called from Τάγαϛ, a town and river in Lycia, in the South of Asia Minor. Derivative jet-black; jetty, Chapman, tr. of Homer, II. ii. 629 ; jett-i-ness.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 348, entry 10

kol-merktr, participle, black as jet; kolmerkt klæði, Sturlunga Saga ii. 32, Vm. 126.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 605, entry 35

Surtr, m., genitive surts and surtar, [svartr], the Black, the name of a fire-giant, the world-destroyer …; Surta(r)-logi, the flame of Surt, the last destruction of the world by fire, Vafþrúðnis-mál 50: curious is the phrase, gott er þá á Gimli með Surti, Edda … surtar-brandr, m. 'surts-brand', is the common Icelandic word for jet … The word is found on vellum MS. of Breta Sögur (1849) 116, and is therefore old, and interesting because the name of the mythical fire-giant and destroyer is applied to the prehistoric fire as a kind of heathen geological term. 2. in local names; Hellinn Surts (modern Surts-hellir) is the name of the famous cave in Iceland; hellinn Surts, Sturlunga Saga ii. 181 … II. a nickname and proper name, Landnáma 2. the name of a black dog. surtar-epli, n., botanical 'Surt's apple,' the pod or capsule of an equisetum, Eggert Itin. 434.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 76, entry 13

BRANDR, m. I. [compare brenna, to burn; Anglo Saxon brand (rare)], a brand, firebrand; even used synonymous with 'hearth', as in the Old English saying, 'este (dear) buith (are) oun brondes', East England Specimens; b. af brandi brenn, Hává-mál 56; at bröndum, at the fire-side … compare eldi-brandr. 2. [compare Danish brand, German, brand], a flame; til brands, ad urnam … surtar-brandr, jet; vide brand-erfð. II. [Anglo Saxon brand, Beowulf verse 1454; Scottish brand = ensis; compare to brandish], the blade of a sword; brast þat (viz. the sword) … víga-brandr, a war-brand, a meteorite III. a frequent proper name of a man, Brand.

A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary (1848) Joseph Bosworth at pages 45, 66, 102, 144, 173 and 186

At page 45

Blæc: genitive, masculine, noun, blaces: feminine, blæcre; se blaca, adjective, Black … A black fossil, jet. Blæc hrem, es; masculine, A raven …

At page 66

Dæg hræfen; dæg hræfnes; masculine, A day raven.

At page 102

Gagates [gagat-stán, Benson's Vocabularium Anglo-Saxonicum, 1701] The agate or jet, a precious stone, Dictionarium Saxonica-Latino-Anglicum, opera et studio Guliel. Somneri, 1659; Lye's Dictionarium Saxonico et Gothico-Latinum, 1772.

At page 144

Hræfen, hræfn, hrefen; genitive, hræfnes; masculine, 1. A raven. 2. The Danish standard. Derivatives Dæg-, niht-. Hræfen-cynn Raven or crow-kind. -fót Raven's or crow's foot. -leac Raven leek, ragwort.

Hræmn A raven, vide hrem.

Hrefen, hrefn A raven, vide hræfen, derived from.

Hrem, hremn A raven. -fót Raven's foot, Lye's Dictionarium Saxonico et Gothico-Latinum, 1772 vide hræm.

At page 173

Niht hræfen, niht hræm A night raven … niht róc Night-rook, raven.

At page 186

Remn a raven, vide hrem.

The Jet Rock

As exposed on the Yorkshire coast, the Jet Rock is essentially a group of dense, finely laminated, dark brown shales 8.8 metres in thickness, with several beds of calcareous concretions, some pyrite-skinned. The shales are akin to oil shales; although they have not been exploited, they have yielded, on laboratory distillation, 54 - 86 litres of sulphurous oil to the ton (Hemingway 1958, pp. 16, 48). With advanced technique they might become an economic asset. The Jet Rock is capped by a thin and platey argillaceous limestone, the Top Jet Dogger (100 - 150 mm), a good horizon marker, which served as a strong roof for adits driven into the shales in search of jet.

The shale laminae range in thickness from 0.10 to 0.30 millimetres in thickness. Each is compound, with a lower lamina of angular detrital quartz (12 microns average diameter), of variable thickness and remarkable lateral persistence; together with randomly distributed grains, quartz forms up to 20 per cent of the rock. This passes up into a clay film with abundant minute wood flakes elongated in the plane of the bedding. The laminae are regarded as annual (Hallam 1967b), resulting from the seasonal fall of dead plankton to the sea floor. Disaggregated shell debris, carbonate micrite lenses, spore cases and pollen, dahllite and collophanite fragments and micaceous (? illite) flakes are common. Pyrite is abundant, up to 15 per cent, primarily in the form of spherical aggregates about 5 microns diameter (Love 1962), though also in larger compound forms, Hallam (1967b, p. 420) has pointed out that, of the two common bivalves, Bositra radiata occurs in great abundance in the lower two metres of the Jet Rock, but above is replaced by Inoceramus dubius. The index ammonite as well as H. elegans and Eleganticeras are frequently pyritized, as are the bivalves.

The Top Jet Dogger (10 cm) is petrographically distinctive, being a sparry limestone with abundant pyrite and interlaminated with stained clay. It passes inland into an argillaceous micrite which lacks bedding and in this form is also found on the east side of the Peak Fault (p. 181).

Whitby Jet

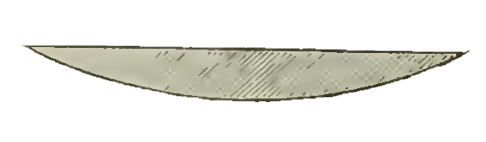

'Hard' jet occurs most abundantly in the upper three metres of the Jet Rock. It is relatively tough, rather than hard, with a silky lustre, and contrasts with 'soft' jet, which is more brittle and is found in the overlying Bituminous Shales and those of the Middle Jurassic. In the Jet Rock, jet is relatively rare and occurs only sporadically in isolated masses, locally known as 'seams', which assume one of two forms. Plank jet (Anon. 1816), by far the more common, lies in the plane of the bedding. It is elongate in plan and plano-convex in section. The largest piece of jet known to occur in one piece is said to have been 1.9 metres in length, 115 - 140 millimetres wide and 28 millimetres thick; it is not known if this specimen was an entire seam or alternatively a joint-controlled specimen, but the latter would appear likely. One seam is said to have weighed 2,350 kilogrammes (Parkin 1882), but this must be regarded as a lograft rather than a single 'plank' and may well have included a dense, silicified core. By contrast, most specimens found by chance at present are less than 10 millimetres thick and 150 millimetres wide.

The second form, cored jet, is spindle-shaped in cross-section with an irregular silica core which runs medially along the length of the specimen, tapering towards each end. Jet forms the outer surface of such specimens, but rarely exceeds 20 millimetres in thickness.

Jet mining was particularly active during the second half of the 19th century for the manufacture of personal and small domestic ornaments. The high lustre that it takes on polishing, as well as its lightness in weight, intense blackness and fine texture, allowed it to be carved into intricate forms which were favoured by contemporary fashion. Jet mining by adit from the outcrop or by 'dessing' (quarrying of the cliff face) was concentrated between Ravenscar and Boulby on the coast, and inland, high on the escarpment by Roseberry Topping [NZ 57903 12590], round the Ingleby re-entrant [NZ 60489 02224], into Bilsdale [SE 56786 96687] and its tributary valleys and south as far as Kilburn [SE 51058 80086]. There is little geological significance in this distribution, as mining was allowed only on agriculturally poor land where the shale tips and acid mine effuent would do little damage. There is no reason therefore to think that jet was distributed other than uniformly, even if sparsely.

Jet is formed from araucarian wood diagenetically altered through a phase when it lost its lignin and was rendered plastic. The woody elements collapsed under the load of superincumbent sediments and the cell cavities were closed. All the structural elements were severely distorted and identification is impossible. Plant structure is however best seen in the chalcedonized cored jet, where all stages may be traced from well-preserved, uncompacted wood to the altered, compressed and ruptured wood of the margins, which forms the jet.

Although the external form of plank and cored jet suggests a direct compression of water-logged stems of wood lying in the plane of the bedding, their microscopic structure proves otherwise. Many are clearly formed from tree trunks split longitudinally, though subsequently rounded by mechanical abrasion. The occurrence of detrital grains within a plank of jet suggests the temporary lodgement of a tree-trunk on a sand-bar or beach and its partial splitting along shrinkage cracks. Such trapped mineral debris includes rounded quartz grains, graded to the now closed crack; more rarely a group of garnet grains from a natural panning of heavy, accessory minerals has been found and one quartzite pebble of 80 millimetres major diameter is known. After renewed transport into the Jet Rock sea, the logs, now abraded and stripped of their cortex, became water-logged and sank to a euxinic sea floor where they were ultimately delignified. Load compression resulted in distortion and collapse of the individual wood elements and the remoulding of the cross-sectional form, the residue being soaked in and in part replaced by organic derivatives. In this softened state the wood accepted the impress of adjacent shells and was even penetrated by the guards of belemnites.

The Bituminous Shales

Above the Jet Rock, the shales of the Whitbian succession imperceptibly but nevertheless clearly change in lithology. Thus the Bituminous Shales smell less strongly of bitumen than does the Jet Rock and they are less well laminated, with only occasional beds of calcareous, pyrite-skinned concretions and rare 'planks' of soft jet.

At page 181

The mobilization of pre-existing calcium carbonate, whether of organic or inorganic origin, could be achieved by the generation of CO2 from the diagenesis of vegetable matter, the larger fragments of which are found as fossil wood in all zones. The muds of the Jet Rock sea were rich in calcium carbonate, the product of bacterial action upon sea water. This would be preserved in the reducing and alkaline interstitial waters and progressively buried. Nuclei might be provided by a shell or shell fragment, but this was not essential. The generation of CO2 would not only mobilize that CaCO3, under more acid conditions, but would also allow the bicarbonate to be displaced upward under continuing compaction (Hemingway 1968, p. 60). When these displaced acid solutions were neutralized by the thin alkaline subsurface zone, precipitation would be initiated, followed by the establishment of a gradient by which carbonate precipitation would continue. Nevertheless concretion growth, once initiated, would not necessarily continue until all the essential constituents such as Ca, Fe, Mg in the adjacent muds were exhausted. Although any marked reduction would clearly slow down growth, the initiation of a second higher bed of concretions would depend on the re-establishment of the vertical chemical gradient in the interstitial waters in the sediment, as well as further sedimentation.

Large concretions in the Jet Rock, the so-called 'Whalestones', are veined by an unusual splintery, brown micro-calcite, which shows flow-structures and contemporary brecciation with some recrystallization (Hallam 1962). The calcite appears to originate from internal differentiation during an early stage of concretion growth, followed by its radial displacement during compaction. This process preceded the more usual septariation.

The final phase of crystallization of the concretion and compaction of the adjacent muds may have been by syneresitic cracking on reduction in volume. These cracks now hold well-crystallized kaolinite or dickite at their inner extremity, the remainder being calcite-filled, with the formation of a typical septarian nodule. Blende is frequently found in Liassic concretions both in syneresis cracks and in the matrix of the nodules.

"On Jet Mining" by Charles Parkin (1881) North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers

It may appear at first that such a purely ornamental material as jet is hardly a suitable subject to bring before the notice of the members of this Institute, but the fact that it is sought for and wrought at considerable personal risk to the miner, and that the mining for it is subject to the Coal Mining Regulation Act, suggests the idea that a few remarks on the question may not be, after all, inappropriate; and although this mineral has been worked for many years, yet so little is known of the method of obtaining it - except those closely interested in the trade - that the writer hopes a brief description of its geological position and the mode of working it will not be out of place in the Transactions of the Institute.

Geological Description

In Dr. Page's Handbook of Geological Terms it is stated that the word 'jet' is derived from Jayet, or Gagites, terms in their turn derived from Gaga, the name of a river in Asia Minor, and that he considers jet to be more of the nature of amber than of coal, stating that in Prussia it is known as 'black amber'.

Young and Bird in their survey relate that in front of the cliff north of Haiburn Wyke, near Whitby, was found the petrified stump of a tree in an erect position, three feet high, and fifteen inches across, having the root - consisting of coaly jet - in a bed of shale, whilst the trunk in the sandstone was partly of petrified and partly of decayed sooty wood.

Phillips, in his Geology of Yorkshire, States that "jet is simply a coniferous wood, and in thin sections clearly shows the characteristic structure, frequently resinous masses of oval figure enveloping larger tissue than occurs elsewhere appear under the microscope" and also "that impressions of ammonites and other fossils appear on surfaces of jet, proving that it has passed through a condition of softness".

The best jet is usually found in the largest quantities towards the base of the upper lias or alum shale stratum, and this portion is generally known as the jet rock; a softer jet is obtained also throughout the shales above, in the oolite series, but in less quantity. The jet rock is about 18 feet thick, lying a few fathoms above Cleveland main bed of ironstone, but below the top seam, which is worked in the Rosedale Abbey and Grosmont district known as the oolite ironstone. The shale is bituminous, and a thin piece lighted will burn by itself; on being exposed to the atmosphere it sometimes takes fire, when it assumes a reddish hue, due no doubt to the iron which it contains; water flowing through this shale leaves it impregnated with alum, and destroys vegetation. An instance of this may be seen at the Slapewath old Alum Works, near Guisbro'. The jet deposits vary in size and although when found are termed seams by the miners, yet this term is not a correct one, the jet lying irregularly through the whole depth of the shale, ranging from a wafer to 5 or 6 inches in thickness; and in length up to several feet, the breadth of the deposit being only few inches.

Mr. Matthew Snowdon, of Whitby, in a letter to the writer, remarks: "We have often got large quantities of jet down here in working the oolite ironstone seam, and in one instance, at Port Mulgrave, we found a deposit for which I had £700 offered. We came across it between the oolite ironstone seam and the freestone." The shape of the deposit, was like that shown in the woodcut.

Mode of Working

The number of men actually employed in jet mining would be somewhat difficult to arrive at, for no accurate record is kept (to the writer's knowledge) either of the men employed or the quantity of material worked per annum. Slight accidents have been of frequent occurrence; and in 1873, a jet miner was reported to have been killed by a fall of shale, owing no doubt, to the way in which the operations were carried on.

The search is always commenced at the outcrop of the alum shale, two or four men forming a company. Shafts are not sunk, either to win or to work it. A drift 6 feet high by 3 or 4 wide is driven in from the outcrop, when these drifts are advanced a few yards, side excavations are made, and the systematic search for jet commenced. The shale over the roof of the side drifts is hewn or wedged down, serving as a platform to Work on, and the whole thickness of the shale is then explored in a fashion somewhat resembling a combination of longwall in coal work, and of stopeing in lead and other metalliferous mines. While the preparatory drifts are being driven, the shale has to be conveyed outside, but in the regular course of working most of it is tossed back, and as little taken out of the mines as possible, horses or lads hardly ever being required. When a discovery is made, the deposit is carefully followed up and excavated in as large pieces as possible; sometimes weeks will elapse and no jet be found, while occasionally exceptional luck is met with, and a great quantity got in a few days. On such occasions the so-called seam is very seldom left until all is extracted and the miners work night and day. The reason for this caution is obvious, for should it become known that a good deposit has been met with, if the mine was left, the jet might be stolen and carried away during the night.

The workings seldom extend beyond a hundred yards at the most from the drift mouth, the shale becoming much more difficult to work as operations are extended from the outcrop.

Means of Ventilation

If, when a drift is driven in for some distance, the prospect is found to be cheering, another drift is commenced running parallel with, and at a distance of about five yards from the one, and the two connected in order to secure ventilation, but the plan more generally adopted at the present time is that of allowing the fall away to the surface when explorations are being made near the top of the jet rock.

An explosion of gas is reported to have taken place some years ago in a jet mine, which was probably due to the oily vapours exuding from the shale; and in the ironstone mines of the district explosions have occurred probably from the same cause. The writer would here acknowledge his indebtedness to a letter which appeared in the Mining Journal for this fact and some other particulars contained in this paper.

Timbering and Blasting

Very little timber is required in these drifts, as the jet-bearing rock is of a very tough character, and no gunpowder or other explosive is necessary in working the shale, the nature of it being opposed to successful blasting, which would moreover injure any jet lying near.

Royalty Charges, Yearly Production and Commercial Value

Owing to the uncertain character of the speculation it is a very difficult matter to fix upon an equitable and reasonable royalty charge, and in most leases or agreements granted for the working of ironstone and other minerals, when jet is included, the terms for working it are embodied in the unsatisfactory words of "a rent to be agreed upon, or, failing agreement, to be determined by arbitration." But it is customary to arrange the matter by a payment varying from 2s 6d up to 3s 6d per week for each miner employed.

The quantity of English jet used per annum at present only amounts to three or four tons, its value varying from £300 to £1,300 per ton, whilst the quantity imported from France and Spain is over 100 tons per year, the foreign supply being so much cheaper, that from France costing the manufacturers only about £30 per ton, and the Spanish from £60 to £140 per ton. The English jet, however, is superior to that obtained from abroad, which is much more liable to fall to pieces on sudden exposure to the sun or other sources of beat.

Locality of Mines

The Yorkshire jet mines are situated in the North Riding, and are to be found principally within a few miles of Stokesley [NZ 52697 09347], at Swainby [NZ 47594 01953], Bilsdale [SE 56786 96687], Rosedale Abbey [SE 72556 95889], and neighbouring district. Jet is also wrought from the sea cliffs, in open quarries in the neighbourhood of Whitby [NZ 90341 10964], the supplies from Kettleness [NZ 83290 15587] having been very large. The Eston [NZ 56431 18364] range of hills has also yielded a good deal of jet in years past. Operations are at the present time going on at Swainby and Bilslale, where Mr. Hall, of Whitby, is working; and on the west side of Rosedale [SE 70605 97202], on Gillbank Farm [SE 70592 96437], where the results are turning out very encouraging; and it is anticipated that other parts of the dale will be explored, the jet from Gillbank [SE 70590 96463] having proved to be of superior quality.

Manufacture

That jet manufacture is of ancient date is evident from the fact of it being on record that from the Sands-End cliffs [NZ 86325 12897] it was procured and used in making ornaments by the Romans at their station of Dinum Sinus (Dunsley Bay) [NZ 85537 11114]. The writer has himself seen a fourteenth century jet ornament.

'Whitby Jet' is a term which seems now to be accepted as a guarantee of the good and genuine quality of the articles manufactured out of this mineral, and the town is justly famed for this branch of industry, for considerable ability and ingenuity is shown in the bracelets, necklaces, ear-rings, brooches, watch-chains, and other fancy articles made. Upwards of 400 men and boys are employed in the Whitby manufacturing trade, who work nine hours per day. The men are paid about 25s per week, and the lads from to 6s to 10s per week.

Mr. Thomas Boyan, one of the principal manufacturers in Whitby, has been kind enough to allow an inspection or his works, which enables the writer to briefly describe the process through which this mineral has to go.

The first process in the manufacture is stripping the skin off the jet (this skin is of a blue colour in that obtained from the alum rock in the cliffs near Whitby, and of a brown colour in that obtained from the jet rock proper in the mines further inland); this operation is done by workmen chipping off the outside with a short chisel; the substance is then passed on to be sawn into various thicknesses and sizes. In this process the greatest economy is observed, and the apparently useless fragments are made up into beads and small ornaments according to their size and shape. The cut pieces are then put into the hands of workers, Who with foot-treadle grindstones take off all the sharp edges and bring them into oval, circular, or other geometrical shapes required. In the next stage it passes into the hands of the carvers and turners, the former with knives, chisels, and gouges, bringing the pieces into beautiful designs, with a degree of accuracy and rapidity that could hardly bc credited. From the carving department the work is transferred to the polishers, who first treat the rough work on polishing boards having a surface of rotten stone and oil, and after this treatment comes the finishing polish, or, as it is termed, 'rougeing' which is accomplished by holding the article against a quickly revolving wheel covered with walrus hide for the broad surfaces, and strips of list fixed on end for the indented or carved portions, or against a revolving brush wheel, all of which are covered with rouge. This rouge consists of a red oxide of iron powder and water. It then only remains to fix the article into its setting to become ready for sale.

Ammonites (molusca shells), commonly known as snake stones, are richly polished and inserted into many of the ornamental articles, and these are obtained in great abundance in the alum shale, and on the seashore scar at Whitby.

There are reasons to believe that the trade will receive a great impetus from the introduction of jet into the enamelling art. Mr. Charles Armfield, Diocesan Surveyor, York, writes to the Builder to call attention to a new means of decoration. It is the invention of Mr. Godfrey Hirst, of Whitby, and consists of a combination of enamel with jet. Mr. Armfield states that, from specimens of the work he has seen, he believes it will form a very valuable artistic addition to the legitimate means of decorating furniture, pulpits, reredoses, etc. It is known that jet is capable of a very high and endurable polish, and he (Mr. Armfield) has seen a thirteenth-century jet cross, found buried on the site of Grosmont Priory, near Whitby, which is still in a perfect state of polish. It may not be generally known that it possesses, in a unique degree, the power of absorbing the radiations of adjacent colours, so that when used with any other colour than yellow, it produces a wonderfully soft effect, and gives a richness of tone which no other black material is capable of producing. That gentleman farther states that he has used jet instead of crystals or sham pearls for jewelling embroidered altar frontals, and was astonished on his first essay with the materials to find that the jet bosses, worked on deep crimson ground, at ten yards distance, looked like carbuncles. At first he thought it was the result of reflection upon the rounded surface of the boss, but a little more thought soon made it apparent that this was not the case, and an experiment with a flat disc of jet, on similar ground, gave a clue to the real cause. This valuable quality of radiation absorption showed itself very strong on the blue, but less on the red, grounds.

In connection with this subject, it seems worthy of consideration that, if the shale excavated from the mines be utilized - and, it must be remembered that it contains both alum and oil - this, in conjunction with the working of jet, might make it a subject more worthy the attention of capitalists.

Phillips says: "The petroleum generally sought for is usually found in most quantity above the jet rock. It is found in the joints of the rocks, in the cells of ammonites, and in other situations which seems on the whole suggestive of a process of distillation from carboniferous compounds in the shales above" and in many of the Cleveland mines the smell of it is very perceptible.

It is asserted that Sir Thomas Chaloner established the first Alum Works in England, at Bellman Bank, near Guisbro', in the year 1600; these were vigorously worked until the year 1792, and in 1852, they were re-opened after having laid idle for sixty years. The Guisbro' works proving so successful, other speculators were induced to embark in these undertakings, about the year 1615, works were opened at Lofthouse, Boulby, Kettleness, Sandsend, and Saltwick near Whitby, all of which were supplied from the sea-cliff quarries of alum rock, within ten miles north, to about seven miles south of Whitby. The Lofthouse and Boulby Works were the most extensive in the kingdom, and the new Boulby Works belonging to Mr. Baker, in the year 1858, employed about 100 hands. The alum trade, doubtless, laid the foundation of the future importance of Whitby. The number of inhabitants of the town in 1610 was 1,500, whilst in 1650 the number had increased to 2,500, due entirely, it is said, to the introduction of the alum trade to the district. The shipments from all the Works were made here and exported to France, Holland and other Continental places, but after some time the demand from abroad began to fall off, until the trade gradually became confined to the home market, supplied through the ports of London and Hull, and of late years nothing has been done at these works, most of which have been permanently closed for some time past.

It is very evident, however, that a large business has been carried on for more than two centuries, which points to the conclusion that the speculation proved to be a remunerative one and the writer is led to consider it a question worthy of investigation, as to how far it would be practicable to combine jet mining with the working and manufacture of alum or shale oil. With to the resources of alum shale now available, they may be considered as practically inexhaustible.

The President said, Mr. Parkin need not have apologized for his paper, which all would consider a very interesting one, whether looked at in regard to jet itself, or in regard to alum works. He was afraid alum works were among the dead industries of the country. He had been connected with them, but the market for alum was gone, and that substance was superseded by other chemical substances.

Professor Lebour exhibited few specimens, which he thought might illustrate some of Mr. Parkin's remarks. There were, he said, specimens of Whitby jet, and among the others were the chief varieties of asphalt and mineral bitumen found elsewhere; and they would see that there was some connexion between all of the specimens. As to the word 'jet', Parkin quoted a derivation from the river Jayet. The same derivation was given for agate. Those substances were not the same things, and yet the same derivation was given for each. One must be wrong. Jet was found in the upper and middle lias of England, also in the Kimmeridgian beds on both sides of the Pyrenees, but chiefly on the south or Spanish side. It was of same character as the English jet, but was not of such good value for commercial purposes. The optical character of jet mentioned by Mr. Parkin was quite new to him; that, he thought, was the most important part of the paper and, in addition to being a subject of interest to capitalists, it was also a subject of interest to physicists. Mr. Parkin had quoted Professor Phillips' description of jet as showing in microscopical sections distinct signs of tissue, so that he looked upon jet as simply altered wood. He (Professor Lebour) had no doubt that Professor Phillips was right as to the sections which he happened to observe, but Professor Phillips' day was not the day of microscopic sections. He (Professor Lebour) had no hesitation in saying that in many sections of jet no tissues of that kind would be observed.

Mr. Parkin said he had seen on the surface of jet the impression of something like a fern, but he had not the specimen to show to the members.

Professor Lebour - that was extremely likely. Anything like jet or asphalt, when in a soft condition, would be just the matter to retain the impression of vegetable matter in perfection.

Mr. Boyd said, it might be reasonable to conclude that the impressions of fossils on jet would be the remains from inland waters, and not from deposits.

Professor Lebour - yes, unless they are drifted.

The President moved a vote of thanks to Mr Parkin, which was seconded by Professor Lebour, and unanimously carried, and the discussion was adjourned.

Abstract. During the middle nineteenth century, jet obtained from Whitby (England) was sought after due to its dark black colour and hardness. This fossilized plant material was used in mourning jewellery, and Whitby hard jet was regarded among the best for carving and bead making. Jet fashion was connected with Queen Victoria, whose long mourning period lasted for almost forty years.

Jet can be found in many locations on Earth and it has been used since prehistoric times for beading and carving. Classic writers, including Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, wrote about its uses in medicine, and during the Medieval Age jet was prized for its black colour, brilliancy and relative scarcity (Ward, 2008). It is a lustrous, opaque, amorphous, black mineraloid with an organic origin: decaying wood from trees related to species of contemporary Araucariaceae subjected to high pressures. This compression could have occurred in salt water (hard jet) or fresh water (soft jet) and jet microstructure still resembles some morphological features of wood, namely the wood vessels. The Mohs hardness of Whitby jet is around 4 and when rubbed against unglazed porcelain it leaves a ginger-brown streak; if touched with a hot needle, jet emits an odour similar to coal (Muller, 2003; Manutchehr-Danai, 2005).

The trees that were the organic source of Whitby jet lived during the Middle Jurassic (175Ma - 161Ma) when the British Isles were located further south, in the area close to the present day Iberian Peninsula. The decaying Araucariaceae logs must have formed a significant part of the plant debris taken by river streams to the sea, where they became embedded in the thick sedimentary layers. They were later submitted to huge pressures from the increasing sedimentary layers, causing the dispersal of some decaying sections but leaving the more resistant ones that became hard jet. Whitby jet occurs in compact lumps of variable size, usually with a very dark black colour. It was especially prized due to the absence of cracks and inclusions from other minerals, such as pyrite. It collected from beaches after sea storms eroded the jet deposits located in the shoreline but also came from small-scale mining (this began around 1840 and stopped in the early 1920s) (Muller, 2003; Ward, 2008; Woodcock and Strachan, 2012).

During the Roman occupation of England, jet from the region of Eboracum (modern York) was already being traded within the empire but only in the nineteenth century were jet deposits exploited on a larger scale in response to a growing interest for semi-precious black stones. The first Whitby jet workshop dates back to 1808 and was established with the assistance of a retired naval officer who realized the potential profits that could be made after seeing some items created by local turners.

The new British railway network facilitated the jet trade and the growing seaside holiday season brought many visitors to Whitby, who could eventually buy the locally produced jewels. The 1851 Great Exhibition was a venue that did much to introduce Whitby jet to the world and some lapidaries received auspicious orders from the European nobility, increasing the prestige of jet.

By 1872, jet trade was well established in Whitby with around two hundred workshops, and fourteen hundred men, women and children engaged in jet trade (Bower, 1873; McMillan, 1992).

The best Whitby jewels were commonly made of hard jet but soft jet was occasionally used for carvings, these were then set into large cabochons made from hard jet. In the decade of 1870, as jet jewels reached international markets and local deposits did not respond to the demand, local and imported jet of lower quality began to be used. This may have been one of the reasons for the decline of the industry, although other factors, both social and economic, were connected with the rapid decline of jet in the 1880s (Kendall, 1974; Ward, 2008).

Victorian Jet Jewels

The Victorian jet jewels were larger because this was required by mid-nineteenth century fashion but they were at the same time lighter than other black semi-precious stones. Although jet is easy to carve, it is difficult to create details without breaking it. The best and bigger Whitby jet pieces were carved into cameos, pendants and other prized pieces while smaller or less valuable lumps were used for beads. Whitby connections with Queen Victoria date back as early as 1850, when Thomas Andrews of New Quay, advertised himself as Jet-ornament Maker to Her Majesty (McMillan, 1992; Muller, 2003; Ward, 2008).

When Prince Albert died, in 1861, the Queen entered into a long mourning period during which only jet jewels were worn at the court. People followed the court fashion and this gave rise to a new etiquette code in which only jet jewels were seen as appropriated for mourning. When Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee (1887) she relaxed her mourning and fashion changed. At the same time, less expensive black pieces made with other materials became available and Whitby workers could not compete with them (Muller, 2003; Finlay, 2007).

Much of the success of Whitby jet was also linked with the Victorian obsession with death and mourning and when these ceased to be fashionable, the industry declined. Nevertheless, as late as 1889, when King Luis of Portugal died, a maid of honour at Buckingham Palace wrote in a letter to her mother: "I am in despair about my clothes, no sooner have I rigged myself out with good tweeds than we are plunged into the deepest mourning for the king of Portugal, jet ornaments for six weeks! … It is a lesson, never to buy anything but black." (Mallet and Mallet, 1968).

By the end of the nineteenth century, long after jet has passed its height of popularity, Queen Victoria still used it, as she wrote in her diary (22nd July 1896): "I wore a black satin dress with embroideries & jet, a lace veil of old point, & diamond diadem & ornaments" (Queen Victoria, unpublished manuscript).

Literature Cited

- "Whitby Jet and its Manufacture" (1873) Bower J. Journal of the Society of Arts 22 at pp 80 - 87

- "Jewels: A Secret History" (2007) Finlay, V. Random House, New York

- "The History of Whitby Jet: Its Workers from Earliest Times" (1974) Kendall, H. Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, Whitby

- "Life with Queen Victoria: Marie Mallet's Letters from Court 1887 - 1901" (1968) Mallet, M., and V. Mallet, John Murray, London

- "Dictionary of Gems and Gemology" (2005) Manutchehr-Danai, M., Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg

- "Whitby Jet Through the Years" (1992) McMillan, Mabel

- "Jet Jewellery and Ornaments" (1994) Muller, H., Shire Album No.52

- "The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art" (2008) Ward, G., Oxford University Press, New York

- "Geological History of Britain and Ireland" (2012) (2nd Edition) Woodcock, N., and R. Strachan, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford

"The Story of Whitby Jet" (1936) Hugh P. Kendall at pages 5 to 14

Pre-Historic

Jet was used by pre-historic man during the Age of Bronze in the manufacture of small articles of personal adornment or utility. It may be thought that, as the neighbourhood of Whitby was the pre-eminent source of the mineral, it would be widely used locally, but the evidence is to the contrary, for few specimens of human handiwork in jet have been discovered in the local burial mounds.

It is not to be supposed that these people sought for jet in any methodical manner, for they can scarcely have known of its provenance. It could be found, as it can today, on the beaches of Robin Hood's Bay, Runswick, Peak, Saltwick, or in any other place where the jet rock is exposed to coastal erosion.

That it was fortuitously found is evident, even to much later ages, for only small articles, such as beads for necklaces, dress toggles, and pendants or charms, are known. Objects of this character are found in widely separated areas of the British Isles, a fact which might appear to indicate that jet was carried from the Yorkshire Coast in barter, much in the same way that nodules of flint were carried over the trade routes in the interior of the country.

But, unfortunately, the word "Jet" has been very loosely used by the antiquarian world in the past, and includes within its scope the impure jet, or lignite, Kimmeridge coal and shale, and cannel coal - all of which have been classed as jet. This indiscriminate use of the word has led to the present misunderstanding that exists, and has given to the Whitby product a prominence amongst pre-historic antiquities that it does not deserve.

We cannot imagine that anything like a trade in jet was carried on in pre-historic times, because the Whitby area was practically isolated, except for periodical incursions of a sporadic character, from the rest of Yorkshire, down to the period of written history; and no such trade, however small, appears possible until about the third century of our era, when the first period of peace in Roman Yorkshire was ushered in.

The evidence afforded by known archaeological discoveries in the past is not enough on which to base any theory of the universal use of jet in the district of its origin, although we should prefer to think so. What finds are recorded are meagre, and altogether unsatisfactory. Three necklaces, a few rings of various sorts, half-a-dozen dress fasteners or toggles, and a couple of pendants, are scattered in various collections in distant museums to represent the total finds of jet in the burial mounds within an area stretching from Boulby to Peak, and a radius of nine miles inland.

Isolated specimens would, doubtless, find their way inland; as, for instance, the jet toggle found by the writer on the Rishworth Moors, near the Lancashire border, which is identical with one found in Fylingdales and now in the British Museum; also, the nine beads, part of a necklace of jet and amber, found in a barrow near Todmorden (West Riding of Yorkshire); and remarkable for the crude boring of the holes, the implement used probably being of flint.

In purely local finds, the necklace found in the Man Toft barrow at Egton, now in the Scarborough Museum, is evidence of jet working of a high standard of workmanship. It is made up of thirty-five pieces, the central one being a rectangular slab with a decoration consisting of incised dots arranged in a diamond pattern; and, in addition to the characteristic barrel-shaped beads, has six conical studs at intervals.

Another necklace, found by the late Canon Greenwell in William Howe, also in Egton parish, had fifteen beads, varying from one inch to one-inch-and-three-quarters in length ("British Barrows", p. 334).

In each case, the beads appear to have been scattered over the burnt-out ashes of the funeral pyre, as no signs of charring appear, as would have been the case had the ornaments been placed upon the body - indeed, they would have been utterly destroyed. It may be that the paucity of jet in the mounds is a result of burning the ornaments with the body, but this is a mere suggestion.

Although there can be no doubt that small quantities of Whitby jet would find its way inland in prehistoric times, there is no evidence to support any suggestion of great use being made of it. Much of the so-called jet is not jet at all, and certainly is not of Whitby origin.

In my conversations with the late Mr. Matthew Snowdon, the probable methods used by the pre-historic jet workers were discussed over actual examples. The following remarks are of considerable value, as being the conclusions arrived a by a practical man with a thorough knowledge of the properties of jet.

Mr. Snowdon writes:

"The tools of the present day are, in some respects, not unlike the tools which must have been used by pre-historic man. They have varied in shape, no doubt, as time went on. For instance, to have made the holes through the slabs and beads, some kind of drill must have been used, for the simple reason that the use of force would not be possible in the course of manufacture without shattering the jet in pieces. Nothing in the nature of burning a way through would be attended with the least chance of success, and, if attempted, the jet would burst into fragments and become useless. The practical worker must need to know from the start something of the nature of rough jet; how the seam runs: where the spar begins, and where it ends, so that he may know the difficulty he may have to encounter during the shaping of the rough jet. Having this knowledge is one-half the battle, without it he would have the spar, and the flaws, without the clear bright surface, thereby reducing the ornament very much in value. Many people have wondered how pre-historic man polished the different shaped pieces to be of such a lasting character as to withstand the test of time. The more we study the difference in appliances, as used in their day, and those of the present time, we can only come to one conclusion - that they were far in advance of ourselves. We are only continuing their work - the method may be different, but they were the pioneers in the art of polishing jet."

"It is well to remember that jet, when scraped, is of a pale brown colour, and has to be brought back to a deep black by polishing. It is not generally known that the scrapings from worked jet when mixed with oil to form a paste, and spread over a piece of sheep-skin, or even cloth will, with perseverance in rubbing, produce a fairly good foundation of polish. And again, using the dry scrapings without oil is sufficient to bring up the final gloss, although it is not to be compared with the present-day method, with all its advantages of wheels and polishes, so well known to the trade."

"It is possible that pre-historic man may have used some such simple methods as those described. Anyhow, he did the work in a way that must call forth our admiration."

"To a practical worker it seems marvellous how these primitive workers fashioned the beads and necklace slabs in the way they have done. How they have drilled the thin slabs is more of a mystery than the beads. Even in these days, with a lathe running at high speed, and a drill made with a shaped neck, so that it clears itself from choking, and finely tempered, it needs a steady hand to meet the half-drilled portion of the slab with the accuracy required: for, in every case, the slab must be drilled from each side."

To conclude the discussion as to the distribution of jet in pre-historic times, it may be mentioned that the investigations of the late Mr. J. R. Mortimer, in East Yorkshire, reveal that out of 893 barrows excavated by him, only 57 contained any ornament of personal adornment, whilst in only 17 of these were the objects of jet. The excavations of Canon Greenwell, in North Yorkshire, yielded a similar result.

Historical references to jet

The Venerable Bede (673-735), in describing Britain, in his first chapter says:

"It has much and excellent jet, which is black and sparkling, glittering at the fire, and, when heated, drives away serpents; being warmed with rubbing it holds fast whatever is applied to it, like amber."

This statement is taken largely from the writing of Caius Julius Solinus, who wrote some five-hundred years earlier than Bede.

"Polyhistor", Gaius Julius Solinus (circa 300 AD)

§ 22.1 Chapter XXII: Britain

§ 22.11 {19} So I may pass over the plentiful and varied abundance of metals in which the soil of Britain is everywhere strong, I will describe the stone gagates. In Britain there is the most, and the best. If you are curious as to its beauty, it is a black jewel; if to its character, it is almost weightless; if to its nature, it burns in water and is quenched by oil. If you are curious as to its power, it detains things close to it when heated by rubbing, like amber.

The elder Pliny (A.D. 23-79) refers to jet, or some similar substance called "gagates", from the original source of supply to the ancients being at Gagae, on the Mediterranean coast of the old province of Lycia, in Asia Minor. It was known to the Greeks at least two centuries before Christ, and the derivation of the word lies in the above and the Old French "jayet", itself probably a corruption of the German "gagat". It was said to be an antidote for poison, if mixed with the marrow of a stag. Some doubt has been thrown on the earlier notices of jet, because "gagate" is also another name for amber; and, as such, is used in old recipes for ailments and the making of charms. It was known in Germany as Black Amber and found in the amber mines there.

The use of jet to ward off the evil eye has persisted from early times, and is still retained in Northern Spain, where the children wear jet beads, in accordance with old custom and superstition.

…

Drayton (1563-1631) published his versical description of England about the year 1613, and thus refers to our Whitby jet:

Out of their crannied cleeves can give you perfect jet.

Chaucer, too, refers to the bill of the "cok, hight Chauntecleer" as shining like jet, in his "Nonne Preestes Tale" line 41:

His bill was black, and it shone like the jet stone

During the excavations from 1922 to 1925, on the site of the Roman Signal Station at Goldsborough, near Kettleness, two perfect jet finger rings were found in the central enclosure, one of which has a pointed projection upon it. In addition, a large number of pieces of rough jet were found, each piece water-worn, and undoubtedly obtained from the beach. Some of these show marks of cutting and sawing, indicating that some member of the garrison was working jet. A spindle whorl turned on the lathe may be an importation, for the workmanship is not that of an amateur. All these are now in the Whitby Museum.

The Romans had a decided partiality for jet ornaments, and much of this work found on Yorkshire Romano-British sites may be safely attributed to the jet rock of Whitby. A small pendant in the form of a bear was found in the Malton excavations, and is almost certainly hard Whitby jet, whilst two others have been found in York.

In the kitchen midden of the Anglian monastery of Streonshalh, discovered in 1867 during clearing for the foundations of a jet shop at the top of the Black Horse Yard in Church Street, beads of jet were found, a large square one, facetted, being now in the Museum. Another round bead comes from the ruins of the Abbey, and is of great age. The account rolls of the Benedictine Abbey for the year 1394 contains the following entry:

"Item for VII rings of gagate to Robert Car, VIId."

this being the earliest documentary evidence of a Whitby jetworker.

In the will of William Salvayne, armiger (esquire) to the Abbot of Whitby, made in 1436, the testator bequeaths to his brother John Salvayne "a large pair of jet rosary beads", and to his sister Sybil a rosary of "coral and jet gauds".

Crosses made of jet were not only in general use as religious symbols, but also as charms against witchcraft, by being hung or fastened to the witch post of the house. One of these, of early date, probably the fourteenth century, may be seen in the Museum. It was found on the witch post of an old cottage in Egton. Jet was considered a potent charm against the evil eye, and was used for that purpose in the neighbourhood of Whitby up to comparatively recent times.

The North Riding Sessions Rolls contain entries of persons described as "jeaters", in 1614. They hailed from Skinningrove and Newholm-cum-Dunsley, and were probably miners.

From the items just quoted it will be seen that it is probable that the working of jet by primitive means has occupied a few craftsmen in Whitby from early times. It was, however, not until the dawn of the nineteenth century that the primitive methods of fashioning jet by knife, file and rubbing stone, gave way to the use of mechanical means in production …

What jet is

Scientific investigation in recent years has finally established the fact that jet is really drift wood; something in the nature of the Monkey Puzzle tree, which has been subject to chemical action in stagnant water, and afterwards flattened by enormous pressure. The jet rock is a lias shale, dark blue to black in colour, dense in texture, and smelling strongly of oil when freshly broken. Its position in the geological strata of the coast is below the bituminous and alum shales of the lias rock, the lias consisting of the solidified mud of an ancient sea which once existed over what is now Cleveland.

The hardest and best variety of jet is found only in the lower bed of the Upper Lias, whilst a softer quality is found in the upper part of the Upper Lias, as well as in the shale above - but this will not stand atmospheric conditions like the harder jet. The latter has a conchoidal fracture, and is highly electric under friction.

The Whitby jet was not all obtained from the cliffs, for there are many old workings, miles away from the sea, as at Bilsdale, Rosedale, Great Ayton and other places. The jet seams may be at low water level, or high in the face of the cliffs, the reason being found in the geological changes which have taken place in the surface of the earth.

The oldest known working is at Oakham Wood, near Hawsker, where definite evidence of workings at some remote period have been found. An Anglo-Saxon bead, now in the Museum, is believed to have come from the deeps of this old mine.