Part 1 Index: Etymological & Teutonic Sources

Part 2 Index: Locative Sources

- Ramsdale Hamlet, Fylingdale's Parish, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale & Ramsdell Chapelries, Hampshire

- Lilla Howe Bronze Age Barrow, North Yorkshire

- Cuerdale Hoard, Preston, Lancashire

- Wade's Causeway, North Yorkshire

Part 3 Index: Danish or Norwegian Origin

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (published sources)

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (table of place-names)

- Viking Society Web Publications

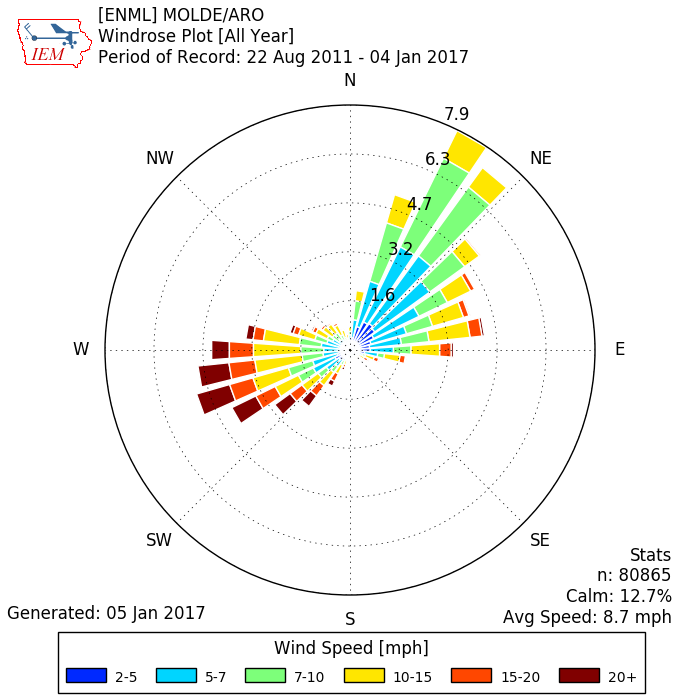

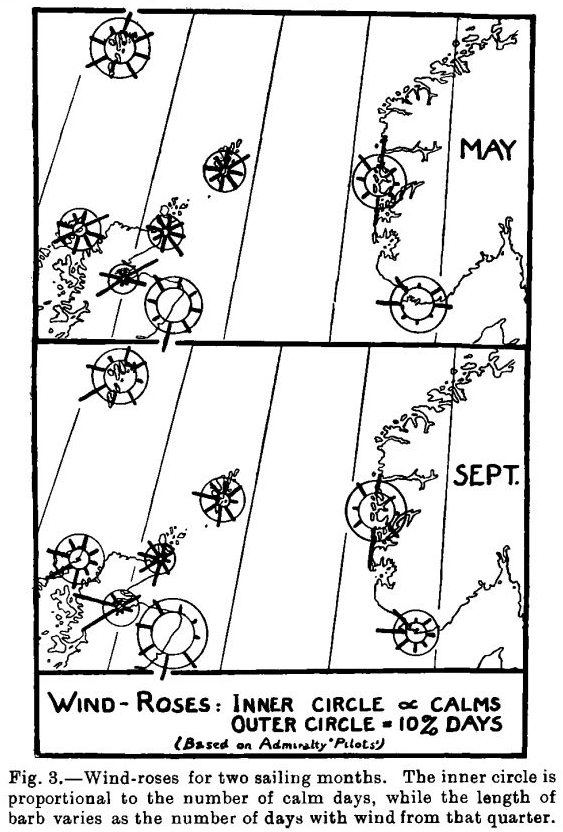

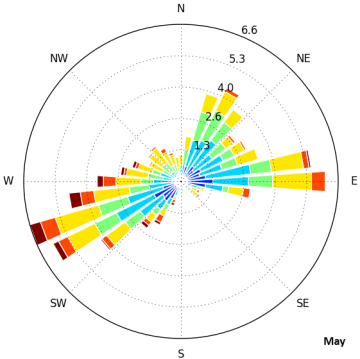

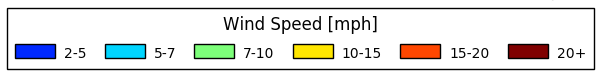

- Molde Wind Roses

- "On dalr and holmr in the place-names of Britain", Dr. Gillian Fellows-Jensen

- "The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire" (1979) A. H. Smith, Volume V

Part 4 Index: General

- Fylingdales: Geographical and Historical Information (1890), Transcript of the entry for the Post Office, Professions and Trades in Bulmer's Directory of 1890

- Fylingdales Parish: Victoria County History (1923) A History of the County of York North Riding Volume 2, Pages 534 to 537

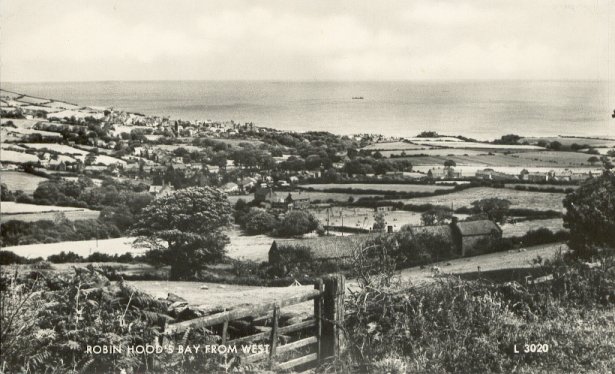

- Ramsdale Mill, Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire - Postcard Views (circa 1917 to 1958)

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Edwardian Postcards (1901 to 1915)

- Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890)

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, Bronze Age Stone Circle, Fylingdales Moor, North Yorkshire

- Robin Hood's Bay - published articles regarding its origin

- Ramsdale Family Register - Home Page

- Whitby Jet - published articles

Etymology

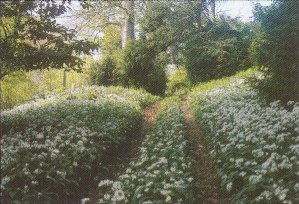

The place name and English surname Ramsdale is locative (both toponymic and topographical) in origin (1) belonging to that group of surnames derived from the place where the original bearer once dwelt or where he once held land, and (2) likely also derived from 'ramsons', being a widespread colloquial name for wild garlic (Allium ursinum) the derivation of which is:

- OE hramsa, 'onion, garlic, ramsons, wild garlic' and 'rank' - the butter and milk of cows which have eaten Ramsons is said to be bitter (rank) - and OE suffix dæl, 'valley, dale' giving OE hramsa dæl, 'wild garlic valley'.

- the first of two possible ON derivations combines ON elements hramsa, rammr ('bitter') and ON dalr, 'dale, valley' giving ON hramsa dalr, 'wild garlic valley', possibly a Scandinavianised form of OE hramsa dæl.

- the second of the two possible ON derivations combines ON hrafn, 'a raven' (hrafns, genitive singular) traced back to, and often spelt, hramn (hramns) according to the morphological rule after which 'n' becomes 'r' after 'm', giving hramns dalr, 'ravens valley'. Cognate with OE hræfn, hræfen, hrefen) 'a raven' and OSax hravan.

"A Modern English - Old English Dictionary" (1927) Mary Lynch Johnson, based on "A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary for the use of Students" (1916) John R. Clark Hall:

- hramsa m (-n/-n) onion, garlic

- hramse, f (-an/-an) onion, garlic

- hramsacrop m (-es/-as) head of wild garlic

"An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language" (1898) Walter William Skeat at page 489

RAMSONS, broad-leaved garlic. (E.) Put for hramsons. 'Allium ursinum, broad-leaved garlic, ramsons'; Johns, Flowers of the Field. Ramsons = rams-en-s, a double plural form, where -en represents the old A.S. plural, as in E. ox-en, and -s is the usual E. plural ending. We also find M.E. ramsis, ramzys, ramseys, Promptorium Parvulorum sive Clericorum Dictionaries Anglo-Latinus Princeps, auctore fratre Galfrido Grammatico dicto, circa A.D. MCCCCXL Ed. A. Way, C.S., 1843, 1853, and 1865. [1440.] page 422; and Way says that Gerarde calls the Allium ursinum by the names 'ramsies, ramsons, or buckrams.' Here again, the suffixes -is, -eys, -ies are plural endings. A.S. hramsan, ramsons; Gloss, to Cockayne, A.S. Leechdoms; a plural form, from singular hramsa. Swedish rams-lök (lök = leek), bear-garlic. Danish rams, or rams-lög (lög = leek) …

"A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary" (1848) Joseph Bosworth at pages 45, 66, 173 and 186

At page 45

Blæc: genitive, masculine, noun, blaces: feminine, blæcre; se blaca, adjective, Black … A black fossil, jet. Blæc hrem, es; masculine, A raven …

At page 66

Dæg hræfen; dæg hræfnes; masculine, A day raven.

At page 144

Hræfen, hræfn, hrefen; genitive, hræfnes; masculine, 1. A raven. 2. The Danish standard. Derivatives Dæg-, niht-. Hræfen-cynn Raven or crow-kind. -fót Raven's or crow's foot. -leac Raven leek, ragwort.

Hræmn A raven, vide hrem.

Hrefen, hrefn A raven, vide hræfen, derived from.

Hrem, hremn A raven. -fót Raven's foot, Lye's Dictionarium Saxonico et Gothico-Latinum, 1772 vide hræm.

At page 173

Niht hræfen, niht hræm A night raven … niht róc Night-rook, raven.

At page 186

Remn a raven, vide hrem.

"A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary" (1848) Joseph Bosworth at pages 41, 42 and 185

At page 41

belene, 1. The herb henbane. 2. A kind of sweet cakes or dainty meat.

At page 42

belone henbane vide belene

At page 42

beolene, henbane vide belene

At page 185

ram, ramm, es; masculine, 1. A ram 2. A battering ram

Rammes-ig, e; feminine Ramsey.

"A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary" (1848) Joseph Bosworth at page 137, entry 25

Henne belle; Henbane, S.

"A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary" (1848) Joseph Bosworth at page 144, entry 26

Hramse, an; feminine, Henbane (hramsa not present)

"An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language (1898) Walter William Skeat at pages 50, 262 and 810

BANE, harm, destruction. (E.) M.E. bane, Chaucer, Canterbury Tales 1099. A.S. bana, a murderer. Icelandic bani, death, a slayer. Danish and Swedish bane, death. Goth, banja, a wound … Derivatives bane-ful, bane-fully.

HEN, the female of a bird, especially of the domestic fowl. (E.) … Derivative hen-bane, Prompt. Parv. page 235; literally 'fowl-poison'; see Bane …

HENBANE. Spelt hennebone (i.e. hen-bane) in the 13th century; Vocabularies, Wright, T. (First Series.) Liverpool, 1857; (Second Series.) Liverpool, 1873. i. 141, col. 2; hennebane in the 15th century, id. 265, col. 2.

"An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary" (1921) Joseph Bosworth, Supplement by T. Northcote Toller at page 562, entry 7 at page 562, entry 6

hræfn A raven. Add Hraebn, hraefn …

"An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary" (1921) Joseph Bosworth, Supplement by T. Northcote Toller at page 563, entry 7

hramsan. Substitute: hramsa, hramse, an; m. f. wild garlic: Hramsa, hromsa … [vide NED rams, ramson].

"Dictionary of Indo-European Languages: Part Three: Vocabulary of the German Language Unit" (1909) Falk, Fick and Torp at page 103, entry 7

hramusa(n) m. … Norwegian, Swiss, Danish, rams m. allium ursinum; Anglo-Saxon hramsa, English 'ramson' …

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 281, entry 42

HRAFN, often spelt hramn, m. [A.S. hræfn; E. 'raven'; German rabe; Danish ravn, etc.; compare Latin corvus] a raven … in the sayings, sjaldsénir hvítir hrafnar, 'white ravens are not seen every day', of a strange appearance; þá er hart þegar einn hrafninn kroppar augun úr öðrum, 'it is too bad when one raven picks another's eyes out'; Guð borgar fyrir hrafninn, 'God pays for the raven', perhaps referring to 1 Kings 17.4 (And it shall be, that thou shalt drink of the brook; and I have commanded the ravens to feed thee there) & 17.6 (And the ravens brought him bread and flesh in the morning, and bread and flesh in the evening; and he drank of the brook) and Job 38.41 (Who prepares for the raven its nourishment when its young cry to God and wander about without food ?). The raven was a favourite with the Scandinavians, as a bird of augury and of sagacity, víða flýgr hrafn yfir grund, 'the raven is a far traveller'; compare the wise ravens Huginn and Muninn, the messengers of Odin, Grímnis-mál, Edda; whence Odin is called hrafn-blætr, m. 'raven worshipper' (Hallfred), and hrafn-áss, m. (Haustl.); hrafna-dróttinn or hrafna-goð, hrafn-stýrandi, a, m. 'lord or god of ravens'; hrafn-freistaðr, m. 'raven friend' … A raven was the traditional war standard of the Danish and Norse vikings and chiefs … also the Anglo Saxon Chroniclers, e. g. the Saxon Chronicle, Asser, A. D. 878, etc. … The croaking of ravens was an omen … when heard in front of a house it betokens death … the ravens are said to hold a parliament, hrafna-þing; and metaphorically a disorderly assembly was called by that name … A black horse is called Hrafn, Edda. In popular lore the raven is called krummi, quod vide Botanical, hrafna-blaka and hrafna-klukka, u, f. Cardamine pratensis, the ladies' smock or cuckoo-flower, Hjalt. Krummi, a, m. a pet name of a raven, perhaps crook-beak … frequent in popular songs … Krumma-kvæði, n. Raven song; krumr, m. = krummi (?), a nickname … krumsi, a, m. = krummi. Proper names of men, Hrafn, Hrafn-kell; of women, Hrefna, Hrafn-hildr: local names, Hrafna-björg, Hrafna-gjá, Hrafna-gil (whence Hrafn-gilingr, a man from H.), Hrafn-hólar, Hrafn-ista (whence Hrafnistu-menn, an old family), etc., Landnámabók: in poetry a warrior is styled hrafn-fæðir, -gæðir, -gælir, -greddir, -þarfr, = feeder of ravens, etc.: the blood is hrafn-vín … a coward is hrafna-sveltir, m. 'raven-starver' …

- hrafn-blár, adj. raven-black

- hrafn-hauss, m. raven-skull, a nickname

- hrafn-hvalr, m. [Anglo Saxon hran or hren = a whale], a kind of whale

- hrafn-ligr, adj. raven-like

- hrafn-reyðr, f. a kind of whale; also called hrefna, balaena

- hrafn-svartr, adj. raven-black

- hrafn-tinna, u, f. 'raven-flint', a kind of obsidian or agate

- hrafn-önd, f. a kind of duck

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 482, entry 20

RAMR, adjective, röm, ramt; rammr is a less correct form … modern usage distinguishes between ramr, strong, and rammr, bitter, whence remma, bitterness: [Northern English 'ram'] strong, stark, mighty, of bodily strength … strong, mighty, with the notion of fatal or charmed power; ramt tré, mighty tree' … vehement, röm ást, strong love … ramr harmr, 'strong grief' … röm víg, 'fiery slaughter' … as a nickname, … II. bitter, biting, opposite to sweet (sœtr); ramr reykr, 'strong reek' … III. in poetical compounds, ram-dýr, of ships; ram-blik, 'the strong beam' = gold; ram-glygg, 'a strong gale'; ram-þing, a meeting = battle.

"An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language" (1898) Walter William Skeat at page 492

RAVEN (1), a well-known bird. (E.) For hraven, an initial h being lost. M.E. raven, Chaucer, Canterbury Tales 2146. - A.S. hrœfn, hrefn, a raven, Grein, ii. 100. + Dutch raaf, raven, + Icelandic hrafn. + Danish ravn. + German rabe, O.H.G hraban. No doubt named from its cry. - KRAP, to make a noise; whence also Latin crepare, to rattle. The crow is similarly named.

RAVEN (2), to plunder with violence, to devour voraciously. (French from Latin) Quite unconnected with the word above, and differently pronounced …

Hyoscyamus niger, commonly known as henbane, black henbane or stinking nightshade, is a poisonous plant in the family Solanaceae which can be found growing on the North Yorkshire moors and hills.

Henbane was historically used in combination with other plants, such as mandrake, deadly nightshade, and datura as an anaesthetic potion, as well as for its psychoactive properties in "magic brews" These psychoactive properties include visual hallucinations and a sensation of flight. It was originally used in continental Europe, Asia, and the Arab world, though it did spread to England in the Middle Ages.

Henbane ingestion by humans is followed simultaneously by peripheral inhibition and central stimulation. Common effects of henbane ingestion include hallucinations, dilated pupils, restlessness, and flushed skin. Over-dosages result in delirium, coma, respiratory paralysis, and death. Low and average dosages have inebriating and aphrodisiac effects.

Henbane leaves and herbage without roots are chopped and dried and are then used for medicinal purposes or in incense and smoking blends, in making beer and tea, and in seasoning wine. Henbane leaves are boiled in oil to derive henbane oil. Henbane seeds are an ingredient in incense blends. In all preparations, the dosage has to be carefully estimated due to the high toxicity of henbane. For some therapeutic applications, dosages like 0.5 g and 1.5 - 3 g were used. The lethal dosage is not known.

Henbane is toxic to cattle, wild animals, fish, and birds. Not all animals are susceptible; for example, the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including cabbage moths, eat henbane. Pigs are immune to henbane toxicity and are reported to enjoy the effects of the plant.

Clinical manifestations of acute henbane poisoning include … slurred speech, difficulty speaking … auditory, visual or tactile hallucinations, confusion, disorientation, delirium, aggressiveness and combative behaviour. Some scholars propose that certain examples of berserker rage had been induced voluntarily by the consumption of drugs such as the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria or massive amounts of alcohol. However, this is much debated and has been thrown into doubt by the following:

- there is no mention of berserkers eating magic mushrooms in the viking sagas nor is there any mention of mushrooms in the sagas or any other written texts or archæological evidence dating from the viking era;

- the discovery of henbane seeds in a Viking woman's grave unearthed at the ring fortress of Fyrkat, near Hobro, Denmark in 1977.

Given that crushing and rubbing henbane petals onto the skin produces a numbing effect along with a mild sensation of flying, this finding has led to the theory that henbane - rather than mushrooms or alcohol - was used to incite the legendary rage in berserkers. The henbane seeds were found in a small purse. If thrown onto a fire, a mildly hallucinogenic smoke is produced. Taken in the right quantity, the seeds can produce hallucinations and euphoric states. Henbane was often used by the witches of later periods. It could be used as a 'witch's salve' to produce a psychedelic effect if the magic practitioners rubbed it into their skin. In her belt buckle was white lead which was sometimes used as an ingredient in skin ointment.

Hyoscyamus niger, black henbane, Keith Cleversley January 2002

Family: solanaceae

Genus: Hyoscyamus

Species: niger

Common names:

- Black Henbane

- Altercum (Arabic)

- Apolinaris (Roman, 'plant of Apollo')

- Asharmadu (ancient Assyrian)

- Banj (Persian)

- Bazrul (Hindi)

- Belendek (Anglo-Saxon)

- Beleno (Spanish)

- Belinuntia (Gaelic)

- Bengi (Arabic)

- Bilinuntia (Celctic, 'plant of Belenus')

- Bilzekruid (Duch)

- Blyn (Bohemian)

- Bolmort (Swedish)

- Csalmatok (Anglo-Saxon)

- Bulmeurt (Danish)

- Dioskyamos (Greek, 'god's bean')

- Giusquiamo (Italian)

- Gur (ancient Assyrian)

- Hyoscyamus (Roman)

- Hyoskyamos (Greek, 'hog’s bean')

- Jupitersbon (Swiss, 'Jupiter’s Bean')

- Kariswah (Newari)

- Khorasanijowan (Bengali)

- Lang-tang (Chinese)

- Lang-thang-tse (Tibetan)

- Sickly Smelling Nightshade

Hyoscyamus niger is either an annual or a biennial, depending on location. It is an upright plant that grows up to 80cm and has undivided, very pungent leaves. The flowers are in thick panicles, and this species has the largest flowers of the Hyoscyamus genus. They are generally pale yellow with violet veins, though some have lemon or bright yellow flowers without veins. The seeds are black, very small, and usually remain in the fruit (Ratsch 1998, 279).

Hyoscyamus niger is the most widely distributed henbane plant, and is found in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Himalayas. It has become naturalized in North America and Australia (Rastch 1998, 279).

Traditional Uses

H. niger is discussed in ancient Greek literature under the name "apollinarix", the plant of the god Apollo. Dioscorides, the famous ancient Greek pharmacologist and botanist who wrote one of the most influential herbal books in history, a five volume set called "De Materia Medica", was familiar with the medicinal value of black henbane. Medieval Anglo-Saxon pharmacopeias also touted the healing properties of the plant. It has also been suggested that henbane was the magic nepenthes in Homer's Odyssey, the drug which Helen gave to Telemachus and his comrades to make them forget their grief. It is thought that henbane under the name of hyoskyamos was sacred to the goddess Persephone (Hocking 1947).

H. niger was used as a ritual plant by the pre-Indo-European peoples of central Europe. In Australia, handfuls of henbane seeds were discovered in a ceremonial urn along with bones and snail shells, dating back to the early Bronze Age. During the Palaeolithic period, it has been speculated that henbane was used for ritual and shamanic purposes throughout Eurasia. When the Palaeoindians migrated from Asia into the Americas, they brought with them their knowledge of the use of the plant. When they were unable to locate Hyoscyamus niger, they substituted the very similar and related tobacco plant (Nicotiana tabacum) (Hofmann et al. 1992).

The Gauls of ancient Western Europe poisoned their javelins with a decoction of henbane. The plant's name is derived form the Indo-European 'bhelena' which is believed to have meant 'crazy plant'.In the Proto-Germanic ancestral language of modern English and German, 'bil' seems to have meant 'vision' or 'hallucination', and also 'magical power, miraculous ability'. There was even a goddess known as Bil, a name interpreted as 'moment' or 'exhaustion'. The goddess Bil is understood to be the image of the moon or one of the moon's phases. She may have been the henbane fairy or the goddess of henbane, and it's speculated that she may have even been the goddess of the rainbow; 'Bil-röst' is the name of the rainbow bridge that leads to Asgard. 'Bil' then would also be the original word for 'heaven's bridge' (Hofmann et al. 1992).

The Assyrians knew henbane by the name of sakiru. They used the plant as a medicine to treat a variety of ailments and they also would add it to beer as a way of making it more intoxicating. It was also used as a ritual incense made by combining black henbane with sulfur to protect the user from black magic. In ancient Persia, henbane was called bangha, a name that was later used to describe hemp (Cannabis sativa) and other psychoactive plants. Persian sources suggest that henbane has had a religious significance throughout history, with many journeys to other worlds and visions described as being evoked by various henbane preparations (Ratsch 1998, 279-280).

King Vishstap, who is known historically as the protector of Zarathustra, imbibed a preparation of henbane and wine known as mang. (It has also been speculated that the potion he drank was a mixture of haoma and henbane in wine). After drinking this concoction, he fell into a sleep so deep it seemed deathlike, lasting three days and three nights. During this time, his soul journeyed to the Upper Paradise. In Persian folklore, Viraz, another visionary, also made a three-day journey into other worlds by using a mixture of henbane and wine. As the story goes, at the end of the third night, “the soul of the righteous”, meaning Viraz, felt as if it were in the midst of plants, inhaling their heady scent, sensing an intensely fragranced breeze that blew in from the south. The soul of the righteous, Viraz, inhaled the wind through its nose and awoke enlightened (Couliani 1995 cited in Ratsch 1998, 279-280).

The Celts consecrated black henbane, known to them as beleno, to Belenus, the god of oracles and the sun, when they would burn it as a fumigant in his honour. Henbane also appears to be one of the most important ritual plants of the Vikings, since Iron Age Viking gravesites were found to contain hundreds of henbane seeds. An archeological dig of the ancient gravesite in Denmark yielded a significant artifact, a leather bag worn by the deceased woman which was filled with hundreds of henbane seeds (Robinson 1994).

The oldest ethnohistorical evidence of the Germanic use of henbane as a magical plant can be found in the nineteenth book of the collection of church decrees, the German Book of Atonement. In one passage, the process of a henbane ritual is described in detail: Villagers gather together several girls and select from them one small beauty. They then disrobe her, and take her outside their settlement to a place where they can find 'bilse', which is henbane in German. The chosen girl pulls out the plant with the little finger of her right hand and it is tied to the small toe of her right foot. She then pulls the plant behind her to the river, as the other girls lead her there, each carrying a rod. The girls dip the rods in the river, then use them to sprinkle the young maiden with the river water, in hopes that they will cause rain through this magical process. It is believed that this ritual was associated with the Germanic god of thunder, Donar (Hasenfratz 1992 cited in Ratsch 1998, 280).

The beer of Donar the god of thunder was brewed with henbane, as he was considered an extremely enthusiastic drinker and very skilled at holding his liquor. As a result, henbane was in huge demand in Germany, although it was quite rare there as it was not indigenous. Therefore Germans planted henbane gardens specifically for using in brewing beer. The history of the sites where these gardens once stood is reflected in their modern day names, such as Bilsensee, Billendorf and Bilsengarten (Ratsch 1998, 280-281).

Since its introduction to North America, many indigenous tribes have taken to using the plant in ways similar to Datura. The Seri tribe add the leaves to their chicha, or infuse them in water and drink to create soporific and analgesic effects (Voogelbreinder 2009, 194).

Traditional Preparation

During the Middle Ages and the early modern period of Europe, henbane was associated with witchcraft and magic, in particular with oracles and love magic. It was believed that henbane smoke could make one invisible and that it was an ingredient in witches' ointments. In modern occultism, henbane seeds are used as fumigants to conjure spirits and to summon the dead. The flowing recipe is for a fumigant used in occult rituals:

- 1 part fennel root/seeds (Foniculum vulgare)

- 1 part olibaum - (Boswellia scara)

- 4 parts henbane (Hyoscyamus niger)

- 1 part coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum)

- 1 part cassia bark (Cinnamomum cassis)

One would take this incense into the black forest, light a black candle and set the incense vessel on a tree stump. The mixture would burn until the candle went out, and it is then that one can see the spirits of the dead (Hyslop & Ratcliffe 1989 cited in Ratsch 1998, 281).

The dried, chopped plant matter can be used for incense and in smoking blends, as well as for brewing beer, spicing wine, and making tea. The seeds are the ideal component when making incense. Henbane oil can be made by boiling the leaves of the plant in oil. This can then be used for therapeutic or erotic massage purposes (Ratsch 1998, 279).

One must be very careful to assess henbane dosage properly. According to Lindequist, a therapeutic dose of Hyoscyamus with a standard alkaloid content is 0.5 g, and the maximum daily dosage is 3 g (Lindequist 1993 cited in Ratsch 1998, 279).

Medicinal uses

In addition to its ritual significance, Hyoscyamus niger has significant medicinal importance as well. The use of henbane smoke to treat toothaches and asthma is widespread. In Darjeeling and Sikkim, henbane is used for these purposes, as well as to treat nervous disorders. The plant has also been used since ancient times to heal bones, as an analgesic and antispasmodic, and as a sedative and narcotic. In Nepal, the smoke of the leaves is used to treat asthma. In homeopathic medicine, a preparation of H. niger is well known to be an effective treatment for anxiety, agitation, unease, insomnia and spasmodic digestive disorders (Ratsch 1998, 281).

In China, henbane, known as lang-tang, was steeped in wine and used to treat malaria, mania, skin diseases, and dysentery. The seeds were said to cause one to see spirits if crushed and consumed. The leaves and flowers are still used in TCM to treat neuralgia and gastric spasms. The smoke of Chinese henbane seeds is inhaled as a treatment for coughs, bronchial asthma, rheumatism and stomach aches (Voogelbreinder 2009, 194).

Traditional effects

Hyoscyamus niger conains 0.03 to 0.28% tropane alkaloids, principally hyoscyamine and scopolamine. The parasympathetic effects of the plant are due to these alkaloids. The primary effects include peripheral inhibition with central nervous system stimulation, and last up to four hours. Hallucinogenic effects are also present and can last up to three days. Overdose can lead to delirium, comas, and death. However, there are few reported cases of overdose. Low doses of henbane beer have aphrodisiac effects. Very high doses can lead to delirium, confusion, memory loss, 'insane' states, and 'crazy behaviour' (Ratsch 1998, 282).

Henbane is toxic to grazing animals, deer, fish, many birds, and so forth. Interestingly, pigs are immune to the effects of the toxins and appear to appreciate the inebriating effects of consuming the plant (Morton 1977).

References

- Hocking, G.M. Henbane: Healing Herbs of Hercules and Apollo. Economic Botany 1 (1947): 306 - 316.

- Hofmann, A., Ratsch, C., Schultes, R., Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. Rochester: Healing Arts Press, 1992.

- Morton, J. Major Medicinal Plants: Botany, Culture and Uses. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, 1977.

- Ratsch, Christian., The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and its Applications. Rochester: Park Street Press, 1998.

- Robinson, D. Plants and Vikings: Everyday Life in Viking-age Denmark. Botanical Journal of Scotland 46, no. 4 (1994): 542 - 551.

- Voogelbreinder, Snu, Garden of Eden: The Shamanic Use of Psychoactive Flora and Fauna, and the Study of Consciousness. Snu Voogelbreinder, 2009.

"Sagas of the Solanaceæ: speculative ethnobotanical perspectives on the Norse berserkers" (2019), Karsten Fatur, The Journal of Ethnopharmacology

A new study on the legendary Viking warriors known as berserkers suggests that they were able to achieve their battle trances and ferocity through the use of henbane. The article by Karsten Fatur, an ethnobotanist from the University of Ljubljana, also offers evidence to refute the possibility that a particular type of mushroom was used by the Norse to become these warriors. The study was published earlier this year in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology.

Very little is known of the berserkers, but scattered accounts of them appear in sagas and Norse mythology. It is thought that the word berserker comes from 'bear skin' because they wore animal pelts in battle. Fatur offers this description of them:

"The berserkers were said to be not just ordinary warriors, but rather to fight while in a specific trance-like state, which was likely helpful in dissociating them from the close-up atrocities they would have seen and committed in battle. This state has been variously claimed to involve anger, increased strength, a dulled sense of pain, decreases in their levels of humanity and reason, behaviour akin to that of wild animals (including howling and biting on their shields), shivering, chattering of their teeth, chill in the body, and invulnerability to iron (swords) as well as fire. Additionally, they were said to attack enemies indiscriminately with no sense of friend or foe and to throw off their armour in battle."

"2. Berserkers"

"Exactly who the berserkers were is a matter of controversy in itself. Originally, the term is thought to have emerged in reference to a specific hero in Norse mythology who fought without armour, thus leaving him 'ber sark' or bare skinned (Fabing, 1956). Then, during the Saga period (870 - 1030 CE) in Iceland and Scandinavia, a group of warriors arose known by the same name before their sudden disappearance around the 12th century CE (Fabing, 1956). Actual direct references,however, are often unclear; even the meaning of the word 'berserker' has been thought to perhaps mean 'bear skin' rather than 'bare skin' and refer to these warriors wearing bear or animal pelts in their battles (Liberman, 2004; Wade, 2016)."

"This lack of information exists in large part due to the fact that knowledge of the berserkers was not recorded substantially until after the tradition had been outlawed by the Christian church while seeking to stamp out paganism and because the writings that did exist were often made by Christian writers with an agenda to denounce these traditions (Wade, 2016).

"Some archæological items from the period display images of warriors whose bodies are covered in animal skins, and various myths among the Norse peoples point to warriors dressing in the skins of bears and wolves to gain their ferocity, but there is no concrete way to associate these phenomena (Wade, 2016)."

"Iconography from the period does also seem to display that berserkers were among the social elite of the time, though this too is open to interpretation (Dale, 2017)."

"Ultimately, all that can be said with certainty is that they were elite warriors who were known for their recklessness in battle and that they may have fought without armour (Liberman, 2004). The berserkers were said to be not just ordinary warriors, but rather to fight while in a specific trance-like state, which was likely helpful in dissociating them from the close-up atrocities they would have seen and committed in battle (Wade, 2016)."

"This state has been variously claimed to involve anger, increased strength, a dulled sense of pain, decreases in their levels of humanity and reason, behaviour akin to that of wild animals (including howling and biting on their shields), shivering,chattering of their teeth, chill in the body, and invulnerability to iron (swords) as well as fire (Dale, 2017; Fabing, 1956; Speidel, 2002;Wade, 2016). Additionally, they were said to attack enemies indiscriminately with no sense of friend or foe and to throw off their armour in battle (Fabing, 1956; Wade, 2016). When the state wore off after about one day, the berserkers were said to experience several days of weakness and dulled mental capacity (Fabing, 1956). Reports also seem to point to clubs being needed to defeat berserkers since blades could not harm them; this has been interpreted by some as potential proof of the term berserker referring to warriors who wore animal skins, since pelts would provide some protection against the cutting of swords but would do very little to protect from the blunt trauma involved in attacks with clubs (Dale, 2017). Though often thought of out of context within popular culture, it has been suggested that the Norse berserkers were in fact part of a larger tradition of Indo-European 'ecstatic' warriors who made use of trance-like states in battle (Speidel, 2002)."

Previous studies suggest that Amanita muscaria, a mushroom commonly called 'fly agaric', was used by the Norse to become berserkers. It is known that in Siberia this mushroom was dried and eaten during religious rituals to achieve a psychoactive state. However, Fatur believes that henbane, also known as Hyoscyamus niger, would be a more likely candidate for the Vikings to have used. This plant, which originated in the Mediterranean but spread northwards to Scandinavia, was well known in the Middle Ages to have psychoactive effects. It was even added to medieval beers, so much so that authorities banned that practice in 1507.

Fatur notes archæological finds from Scandinavia that show henbane being used during the Viking age. This includes a woman's grave in Denmark from around the year 980 that included a pouch of henbane seeds with clothing, jewellery, and other grave goods that suggests she was a priestess or shaman.

The article offers this analysis of why henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) would have been more likely than mushrooms (Amanita muscaria):

"As previously discussed, both substances may cause increases in strength, altered level of consciousness, wild/delirious behaviour, jerking/twitching, and redness of the face, all of which have been associated with berserkers. What makes Hyoscyamus niger a more compelling theoretical cause of the berserker state, however, is its additional symptoms that are not commonly seen in intoxications involving Amanita muscaria. In addition to the previous symptoms, Hyoscyamus niger's alkaloids also have pain killing effects unseen in the compounds within Amanita muscaria, which may account for some of the reports of the supposed invulnerability of the Norse berserkers. Even more compelling is the duration of effects; though the berserker state has been reported to involve several days of side effects after the high has subsided, this is not a common feature in intoxications with Amanita muscaria."

Fatur also notes a few other effects that might have been caused by henbane, which has been seen in studies about modern cases of that plant use. These include the inability to recognize faces (berserkers were said to be not able to distinguish between friends and foes in battle), the removal of clothing, and loss of blood pressure, which might explain why berserkers did not lose much blood when struck by blades. There are some aspects of berserker behaviour which cannot be explained by using henbane, namely the chattering of teeth and the biting of shields.

7. Conclusions

The present article has been able to provide a theory: that Hyoscyamus niger was used by the famed berserker warriors of the Saga period (870 - 1030 CE) in Scandinavia to produce their battle trances. Ultimately, future finds will determine if this theory will be proven or disproven. The most reliable form of archæological/historical data combines paleobotanical and textual/artifactual information in order to provide a complete picture of the past (Merlin, 2003). The present investigation has done just this, showing that at present the data available supports the potential use of Hyoscyamus niger as an intoxicating agent to induce the berserker trance. Although the Amanita muscaria mushroom is a popular theoretical cause accepted by many, we have seen here that the symptomology of the berserker state aligns much better with an intoxication arising from the anticholinergic alkaloids hyoscyamine/atropine and scopolamine. Of the plants that contain these alkaloids, Hyoscyamus niger is the most viable option as a result of its presence in Scandinavia during this time period and its association with various archæological sites that show it was being employed by humans in this time and place and that it was commonly growing as a weed in areas of human habitation. This article must of necessity conclude with the remark that I myself am neither a historian of nor an archæologist of the Nordic region. As an ethnobotanist studying the use of anticholinergic solanaceous plants in Europe, however, this theory came to me as a result of the information present in the literature. Only future research may now confirm or deny the speculative ethnobotanical perspective here presented

Hyoscyamus niger, henbane, black henbane … So poisonous that the smell of the flowers produces giddiness but, in some cultures, used for ritual and recreational purposes due to its strong hallucinogenic properties … Causes … agitation and combative behaviour … The seed heads look like a piece of jawbone complete with a row of teeth. This plant was, therefore, used in dentistry from ancient times. The hallucinogenic, soporific effects of the plant would have made people forget the toothache …

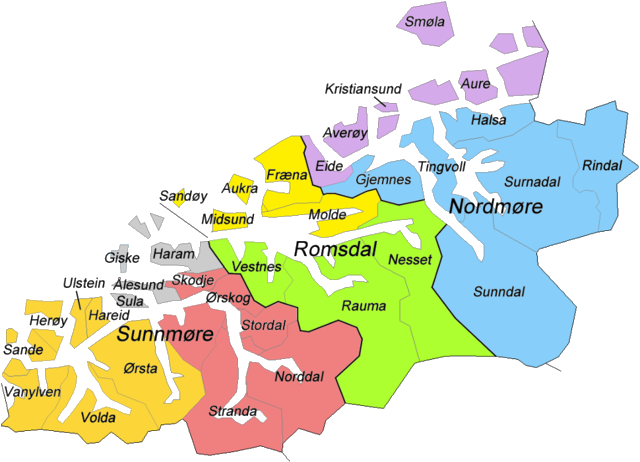

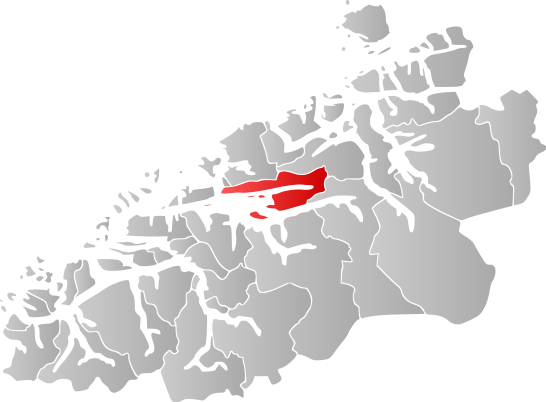

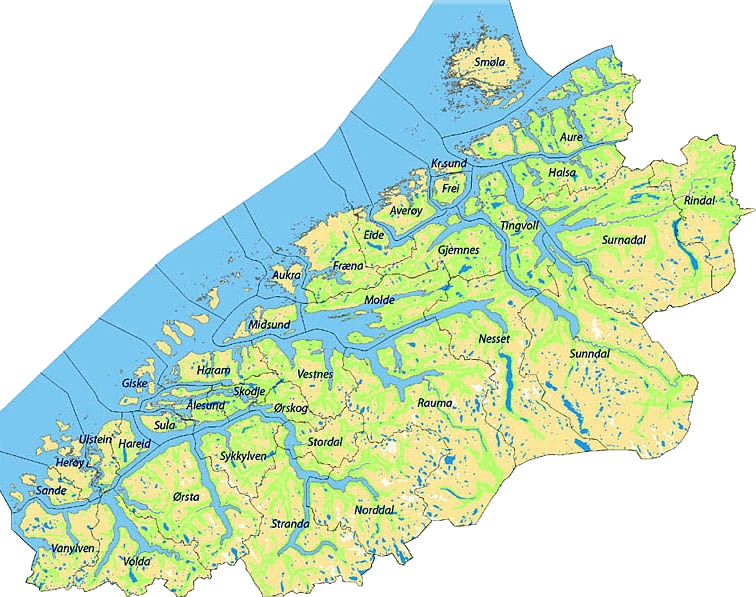

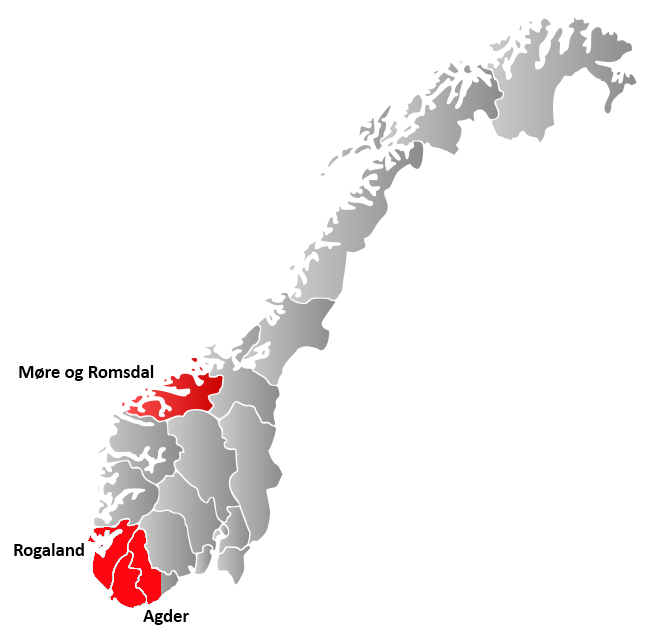

Alternatively, the surname Ramsdale derives directly from the Norse place-name Raumsdalr (the valley of the river Rauma in the counties of Oppland and Møre og Romsdal in Norway - modern: Romsdal) an eponym after "Raum the Old" (Old Norse: Raumr inn gamli), son of King Nór, legendary founder of Norway who may have been descendants of the ancient Gothic "Raumii" tribe. Raums Dale is the modern district of Romsdal in the county of Møre og Romsdal. Raum was said to have been ugly, as was his daughter, Bryngerd, who was married to King Álf. Indeed, in Old Norse, raumr means a big and ugly person. See "An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson:

- Raumar, m. plural the name of a people in Norway: Rauma-ríki, n. a county in Norway: Raums-dalr, m. the present Romsdalen: Raum-dælir, m. plural the men from Raums-dalr: Raum-elfr, f. the river Raum in Norway, Fornmanna Sögur: Raumskr, adjective from Romsdalen, Fornmanna Sögur. ii. 252.

- raumr, m. a giant, Titan, Edda (Gl.) 2. a big, huge, clownish person, Fas. ii. 384, 546, Skíða R. 51.

- ELFR, f., … a proper name of the three rivers called Elbe … Raum-Elfr, the Elb of the Raums (a people in Norway) …

For references to Raum- people and places see "Harald Fairhair and his Ancestors" (1920), "The Ancestors of Harald Haarfagre" (1920) and "Harald, first of the Vikings" (1911)

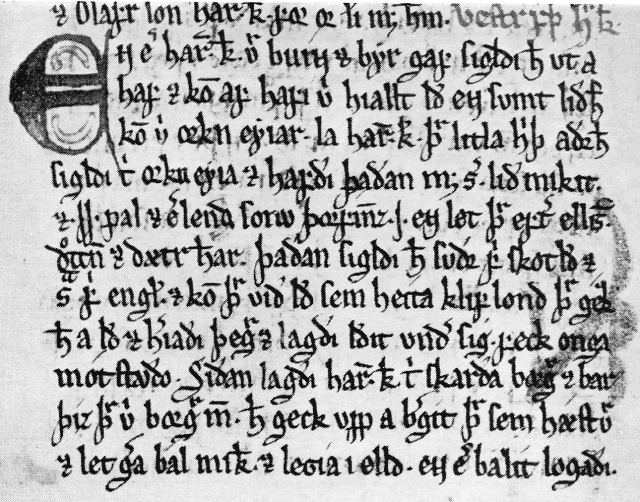

"Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of The Northmen of The British Isles" (Volume IV) The Saga of Hacon and a fragment of the Saga of Magnus with Appendices translated by Sir G. W. Dasent

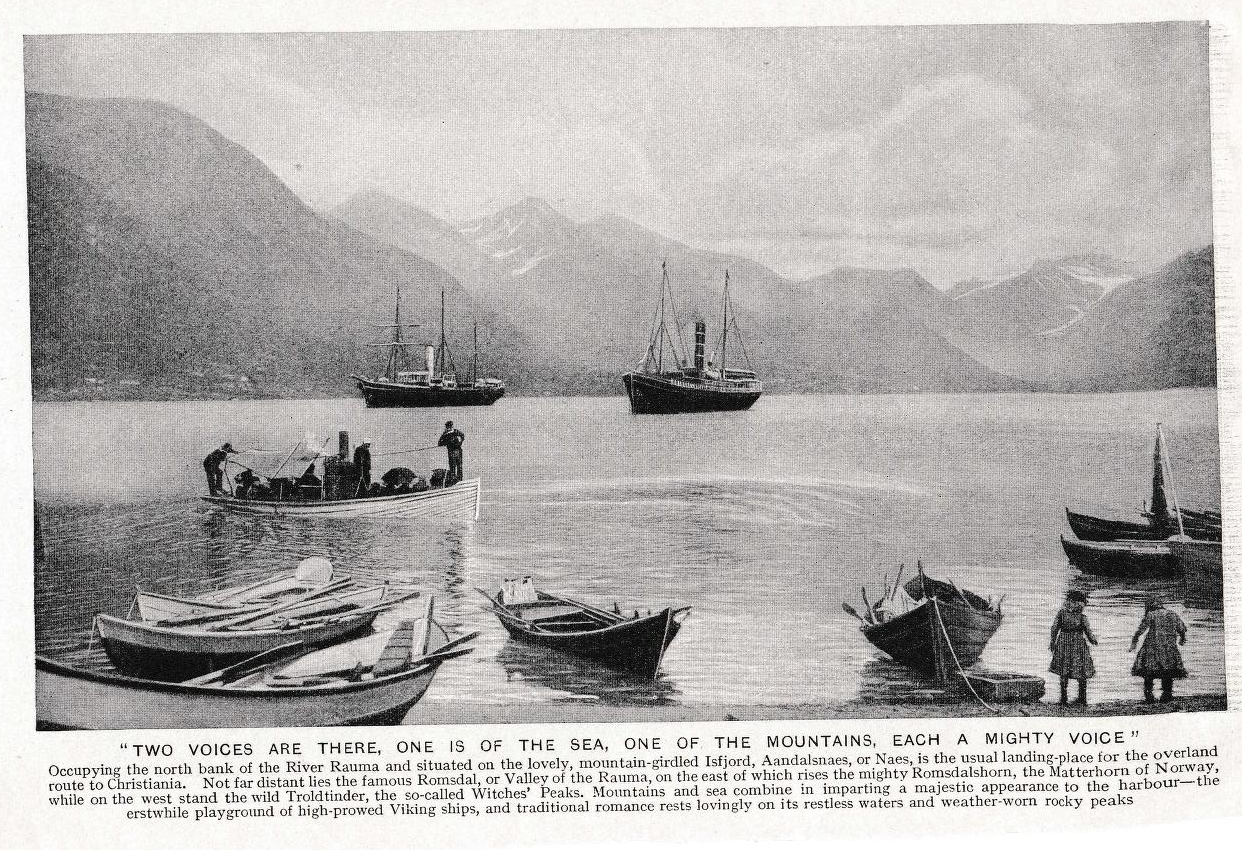

At § 212 on pages 203 and 204: "When King Hacon sailed out of Bergen it was said to him that the Duke had sent men into the stewardships in South Mæren and in Romsdale. … And when they came north off Romsdale-mouth they heard that Finn ball was inside in Ve-isle with his band. They turned at once into the firth, and came on them unawares, and slew Finn and some men with him."

At § 10 on page 16: "King Ingi was at feud with the Drontheimers for that they kept back the levies of men from him and other sea-service. The king fought with them at the Rauma-Thing, as is written in his Saga."

At § 32 on page 35: "Rognavald got the stewardship at Fold and about Oslo; but he had held before the stewardship in Romarick. The men of Rauma called him rather hard in his stewardship; and he stood in need of much, for he had a great company."

At § 205 on pages 195 and 196: "Thence they went south into Romsdale, and slaughtered everywhere the cattle of the king's men. But they laid hands nowhere on the men, for they had all gone south away from them … Arni black was to have the stewardship in Romsdale, and he turned back south to the king …"

At § 293 on pages 310 and 311: "As Sturla says":

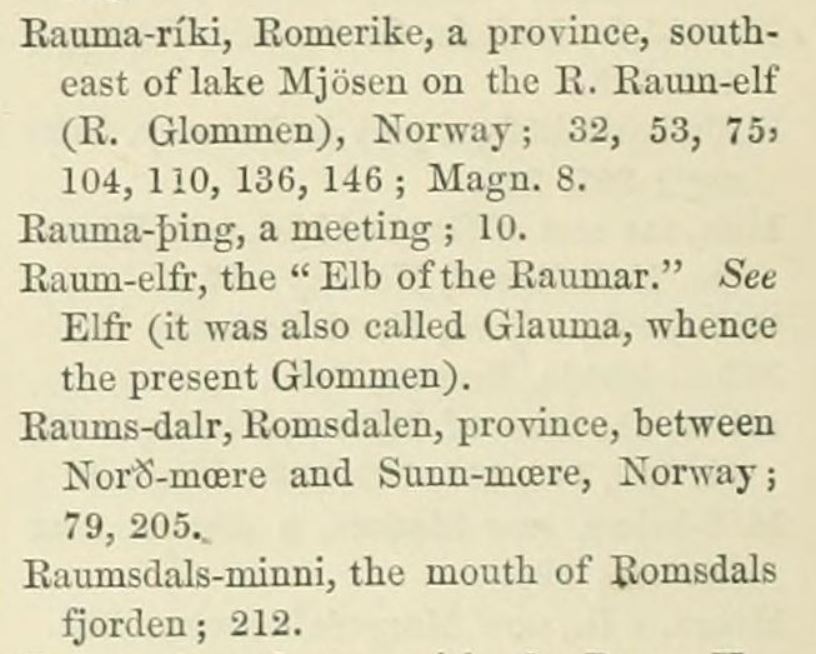

Index of Places at page 463:

At § 79 on page 72: "… When the Ribbalds heard that then they turned east over the fell, and the messengers told the king that there was not less expectation that they might come down into Romsdale or into Mæren."

Index and Names of Places at page 446:

"Norway, I. Virile Ways of the Modern Vikings" (circa 1920) A. MacCallum Scott Volume V at page 3870

Snorri Sturluson, Edda, Skáldskaparmál

2. Glossary and Index of Names edited by Anthony Faulkes, Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London (1998)

Nǫkkvi m. a king in Raumsdalr (Romsdal, Norway) v345/4 (genitive with mœtir, or with ræsinaðr ?, see note and Glossary under nǫkkvi)

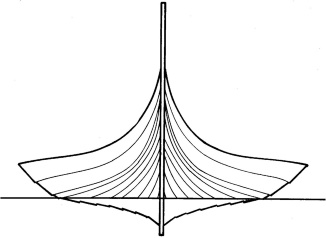

nǫkkvi m. boat (originally a hollowed tree-trunk; Falk 1912, 85) v491/8; cf. v345/4, see note and Index

Raumar m. plural, inhabitants, people of Romerike or Romsdal in Norway v376/1 (Hkr II, III, Fagrskinna)

"A New Introduction to Old Norse, Part III": Glossary and Index of Names (2007) Anthony Faulkes and Michael Barnes, Viking Society For Northern Research, University College London at page 172

Mœrr f. district in Norway (Norðmœrr-Raumsdalr-Sunnmœrr; modern Møre and Romsdal) XVI:9

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson

Raumar, m. plural, the name of a people in Norway: Rauma-ríki, n. a county in Norway: Raums-dalr, m. the present Romsdalen: Raum-dælir, m. plural, the men from R.: Raum-elfr, f. the river Raum-elfr (Raumelfr 'Raum river') in Norway, Fornmanna Sögur: Raumskr, adj. from Romsdalen, Fornmanna Sögur ii. 252.

raumr, m. a giant, Titan, Edda (Gl.) 2. a big, huge, clownish person, Fornaldar Sögur ii. 384, 546, Skíða R. 51.

raumska, að, modern rumska, to say hem! in awakening, Fornaldar Sögur iii. 11.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson

ELFR, f., genitive elfar, accusative, dative elfi, a proper name of the three rivers called Elbe, Latin Albis, viz. Gaut-Elfr, the Elb of the Gauts (a Scandinavian people) = the River Gotha of the present time; Sax-Elfr, the Elb of the Saxons, the Elbe; Raum-Elfr, the Elb of the Raums (a people in Norway), i. e. the present Glommen and Wormen, Bær. 3, Njála. 42. Fornmanna Sögur i. 6, ii. 128, iii. 40, iv. 121, ix. 350, 393, 401, x. 292: Elfar-bakki, the bank of one of these Elbes, Bær. 3, Fornmanna Sögur ix. 269, 274; Elfinar-bakki, Fornmanna Sögur i. 19;, of the river Ochil in Scotland, is a false reading = Ekkjals-bakki, vide Orkney. 12. Compounds: Elfar-grímar, m. plural dwellers on the banks of the Gotha, Fornmanna Sögur vii. 17, 19, 321. Elfar-kvíslir, f. plural the arms of the Gotha, Fornmanna Sögur i. 7, iv. 9, ix. 274; used of the mouths of the Nile, Edda 148 (pref.) Elfar-sker, n. pl. the Skerries at the mouth of the Gotha, Fornmanna Sögur, Fornaldar Sögur; compare álfr, p. 42. 2. metonymically used of any great river, (rare in Iceland but frequent in modern Danish).

Elfskr, adjective, a dweller on one of the Elbe rivers, Landnáma, Fornmanna Sögur ii. 252.

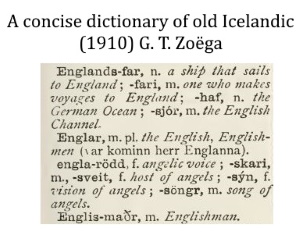

"A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic" (1910) G. T. Zoëga at page 111

elfar-bakki, m. bank of a river.

Elfar-byggjar, -grimar, m. plural, the dwellers on the banks of the Gotha (Gautelfr); -kvíslir, f. plural, the arms of the Gotha, also used of the mouths of the Nile; -sker, n. plural, the skerries at the mouth of the Gotha.

elfr (genitive elfar, dative and accusative elfi), f. river; especially as proper name in Saxelfr, the Elbe; Gautelfr or Elfr, the river Gotha (in Sweden); Raumelfr (in Norway).

The Ynglinga saga, when relating the events of the reign of King Gudröd (Guðröðr) the Hunter relates:

"Álfheim, at that time, was the name of the land between the Raumelfr ['Raum river', lower parts of the modern Glomma river] and the Gautelfr ['Gaut river', the modern Göta älv]."

The words "at that time" indicates the name for the region was archaic or obsolete by the 13th century. The element elfr is a common word for 'river' and appears in other river names. It is cognate with Middle Low German elve 'river' and the name of the river Elbe. The Raum Elf marked the border of the region of Raumaríki and the Gaut Elf marked the border of Gautland (modern Götaland). It corresponds closely to the former Norwegian province of Bohuslän, now in Sweden.

The name Álfheim here may have nothing to do with Álfar 'Elves', but may derive from a word meaning 'gravel layer'.

However, the Saga of Thorstein, Viking's Son claims that the two rivers and the country was named from King Álf the Old (Álfr hinn gamli) who once ruled there, and that his descendants were all related to the Elves and were more handsome than any other people except for the giants, a unique and possibly corrupt reference to giants being especially good looking. The Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum also mentions the special good looks of the kindred of King Álf the Old.

Álfr hinn gamli: in proper names, hinn Gamli is added as a soubriquet, like 'major' in Latin, to distinguish an older man from a younger man of the same name; hinn gamli and hinn ungi also often answer to the English 'father and son'; thus, Álfr Gamli and Álfr Ungi, old and young.

"North Men - The Viking Saga 793-1241" (2015) John Haywood at page 27

Chapter 1: Thule, Nydam and Gamla Uppsala - The Origin of the Vikings

… Around eight tribes lived in Norway; their homelands can be identified with some certainty because they are etymologically related to the names of regions of modern Norway. The Raumarici most likely lived in Romerike, the Alogi in Hålogaland north of the Arctic Circle, the Rugi in Rogaland, and so on. Rodulf's Rani probably lived in Romsdal, the valley of the river Rauma, in the west of the country. Thanks to its rugged geography, Norway remained a land of local tribes even at the beginning of the Viking Age. Elsewhere, most of the tribes named by Jordanes had vanished by this time …

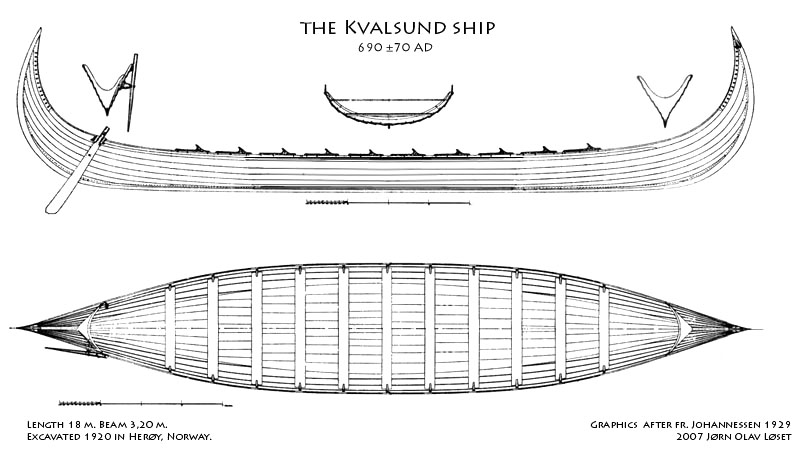

"Native Families of the Orkney and Shetland Islands" (13 May 1999) Niven Sinclair

Drawing on the available historical research sources such as Craven, Peterkin's Rentals. J Clouston's Records of the Earldom of Orkney and Roland William St Clair's The Clair of the Isles, these native families of the Orkney and Shetland Islands (and, to a lesser extent, Caithness) are the descendants of the Initial Norse Viking colonists who consolidated and extended the Northern Territories of the Orcadian 'jarldom' under the leadership of the family of Jarl Rognvald 'the Wise' of Moeri and Rhomasdahl in Norway and, more particularly, by his natural son, Jarl 'Turf' Einar - so-called because he taught people how to burn peat.

The surname Ramsdale is related etymologically to the surnames Ramsden, Ramsdell, Ramsgill and Ramsbottom, all of which

- derive from the same OE element hramsa and/or ON element hramns, and

- tend to be associated with Lancashire and Yorkshire.

The most probable source of the surname is Ramsdale Hamlet [NZ 92722 03762] in Fylingdale's Parish, North Yorkshire. This parochial chapelry lies south of Whitby parish and contains the villages of Robin Hood's Bay and Thorpe, or Fyling Thorpe (Presterthorpe, 13th century), and the hamlets of Normanby, Parkgate, Ramsdale, Raw (Fyling Rawe, 16th century), and Stoupe Brow.

The actual derivation of the surname will likely only be discovered through improved Y-DNA testing of males of the Ramsdale surname to more accurately determine their paternal line.

"Surnames, DNA and Family History" (2011) George Redmonds, Turi King and David Hey at pages 4 to 7 and 215 to 217

Introduction at page 4

Reaney's Dictionary of Surnames

Reaney's dictionary often quotes early examples of surnames in districts other than those where they were found in the post-medieval period; he thus sometimes gives a misleading impression of where a surviving family name originated. For instance, he suggested that the surname Ramshaw had the same derivation as surnames derived from place-names such as Ravenshaw (Warwickshire) and Renishaw (Derbyshire). In fact, Ramshaw is a County Durham surname which is derived from Ramshaw Hall, Evenwood, near Auckland. The Durham hearth tax returns of 1666 list five households of Ramshaws in Chester-le-Street ward, two in Darlington ward, and one in Stockton ward. Of the 739 people who bore the surname in the 1881 census, 396 lived in County Durham and 149 in Northumberland; none was found in the heartlands of the Renshaws and Renishaws. Although he knew that his own name came from Ranah Stones Farm in south-west Yorkshire, Reaney usually missed the point that uncommon names are associated with particular districts and often have single-family origins.

Reaney's achievement was considerable. His dictionary is still a first port of call. Yet his conclusions about the etymology of a name can often be shown to be wrong. He had no interest in the geographical distribution of names, nor in the ways in which medieval surnames continued to evolve in later centuries. His opening words in his Introduction were:

"The purpose of a Dictionary of Surnames is to explain the meaning of names, not to treat of genealogy and family history".

Yet by ignoring genealogy his explanations of the etymology of a name are often incorrect. Every family name, however common, had a single progenitor and every effort must be made to identify him and his immediate descendants if we are to understand how a name arose and perhaps evolved into something different. The expertise of the philologist in interpreting the earliest recorded form of a surname cannot by itself be trusted to offer a proper account of the meaning of a modern name. A multi-disciplinary approach is necessary for a proper understanding of the etymology of a surname and its subsequent development.

… Reaney's pioneering work was valuable at the time and can still be useful, but his real purpose seems to have been to explain the meaning of medieval names, whether or not they became hereditary and whether or not they survived. Nor was he much concerned with the ways that surnames might evolve over the centuries. Unfortunately, many of Reaney's flawed explanations are repeated in other dictionaries and are accepted as accurate in a variety of historical publications, despite all the new work of the past half century.

Introduction at page 5

The English Surname Series

… Meanwhile, George Redmonds' 1970 Leicester PhD thesis was published as English Surnames Series, 1: Yorkshire, the West Riding (1973). This book was the first to champion the idea that very many English surnames have a single-family origin. Some of these have remained rare, but from the sixteenth century onwards, as the population grew, families that produced numerous sons spread from their point of origin into the neighbouring towns and country, side, and occasionally much further.

Introduction at page 6

The Leicester approach emphasized genealogical methods in the context of the growth of local communities and stressed the fluidity of development in the centuries after surnames first became hereditary. In the post-medieval period, numerous surnames changed in minor ways and some altered out of recognition in the course of only two or three generations. Genealogical methods have to be used to link modern names with those recorded in historical sources and to establish the variant forms of a surname before plotting them on distribution maps. This is easier said than done, for some names became unrecognizable while others shaded into each other and even assumed the forms of local place-names and personal names with which they had no real connection. It is unwise to guess the meaning of a family name simply from its modern spelling.

For ordinary people whose surname has changed from the original medieval form, the most likely explanation is that an ancestor migrated to a new neighbourhood where the name was unfamiliar and patterns of speech were different. The origins of some family names are puzzling because both the surname and the place-name from which they were derived have changed in spelling and pronunciation over time. For example, the surname Shufflebottom comes from a place near Bury (Lancashire) that is now known as Shipperbottom. The first record of the surname occurs in 1285 as Richard de Schyppewallebothem, which can be explained as (sheep - well - valley bottom), a similar name to Ramsbottom, not far away. The 1881 national census listed 542 Shufflebottoms, 617 Shufflebothams, and 150 people with many other spellings of this name, most of them in south Lancashire and Cheshire. A further 112 Shipperbottoms were recorded in the census: 108 of them in the Bolton registration district (which included Bury) and the other four nearby in Haslingden. All the bearers of this unusual name, whatever the spelling that they prefer, perhaps share a common ancestor, unless they are descended from what geneticists call a non-paternity event.

Conclusion at pages 215 to 217

The study of surnames was once the preserve of the specialist in old languages. The dictionaries that are still consulted on the shelves of public reference libraries were compiled by philologists in a long tradition that culminated in the work of P.H. Reaney and R.M. Wilson. Knowledge of Old English, Old Norse, Norman French, Middle English, and other languages that have influenced the ways that surnames have been formed is clearly an essential component of a proper understanding of the subject. As with the study of place-names, it is essential to establish the earliest recorded spellings of a surname and to place them in an appropriate linguistic context. But only a small group of scholars who are interested in surnames possess these specialist skills and so the etymologies that have been derived from them have been readily accepted by the public at large.

It is now clear that this approach remains valid only if it takes account of other methods of enquiry. It is not the sole way to the truth. Linguists have often failed to provide correct etymologies because they have not linked the earliest recorded examples with present forms. Although the linguistic approach is usually effective in explaining medieval by-names, it often lacks credibility when dealing with modern surnames, for it has taken little or no account of how very many names have changed over the centuries, often radically, and it has had no interest in the past and present geographical distributions of surnames. Time and time again, compilers of dictionaries have quoted medieval evidence from counties far distant from the present concentration of a name and for which there are no later records. No attempt has been made to show that the early by-names that they unearthed ever developed into hereditary surnames. What Reaney and Wilson produced was not a dictionary of current surnames, but a useful compilation of etymologies of numerous English by-names during the main period of surname formation.

Linguistic analysis remains an important component of the study of sur-tames, but it needs to be subsumed in a multi-disciplinary approach that uses he techniques of genealogy and the knowledge of local historians. Each family name, even if it is one shared by numerous families across the land, should be treated as having a unique history that must be traced back in time step by step. Only by the use of such painstaking methods can we be sure whether a name has retained its early form or has been altered, either subtly or out of recognition, over the centuries.

Genealogical methods can also establish whereabouts a particular surname was formed, or they can at least demonstrate that a distinctive name was confined to a particular locality in the late Middle Ages or by the beginning of parish registration in the mid-sixteenth century. One of the greatest advances in the study of surnames has been through mapping their distributions at various points of time, starting with modern electoral rolls and telephone directories, then going back in time to the 1881 census, the hearth tax returns of the 1660s and 1670s, and possibly to the poll tax returns of 1377-81. Such maps show immediately that the surname Ashurst, for example, was derived from a minor place-name near Wigan and that the bearers of this name have no historical links with similar place-names quoted by Reaney and Wilson in Kent, Surrey and Sussex. If any of the medieval by-names that were formed from these other Ashursts became hereditary surnames, they must have died out quite early.

The local provenance of numerous British surnames, as revealed by distribution maps and genealogical research, suggests that very many of them are of single-family origin. Historians have often been thwarted in their attempts to prove this claim because of the relatively sparse nature of the documentary evidence at the time when surnames became generally adopted. This is why they have welcomed the new technique of DNA analysis of the male Y chromosome with such enthusiasm. Some spectacular results have been achieved and the case for single-family origins of many surnames has undoubtedly been strengthened. Yet this approach alone does not always resolve the problem, for it is often frustrated by what scientists call non-paternity events, chiefly high rates of illegitimacy. The results of investigations into DNA structures are often not sufficiently certain on this point to stand on their own. They have to be considered alongside those of linguistic, genealogical, and historical research.

Genetics has much more to offer family historians than the resolution of this particular problem, however. It can provide a way of determining whether or not two or more names shared a common ancestry, as seemed possible or even likely from the historical evidence. This is not just a matter of connecting names with variant spellings; it can also demonstrate a complete change of a name through the use of an alias, or show that illegitimacy, adoption, or some other form of non-paternity event has occurred. Proving a link between different names has been a particularly exciting new development when different forms of a surname appeared thousands of miles away across the Atlantic. Genealogists have turned to this new technique with enthusiasm and have quickly become the best informed amateurs about the implications of the genetic structure of the male Y chromosome.

The study of surnames is of particular interest to family historians, but it also has wider implications. Surname distributions have much to tell us about the stability and mobility of the British population as a whole over the past few centuries. They demonstrate that, despite the mobility of numerous individuals, most families remained within the neighbourhood or 'country' that had been familiar to their ancestors. London was exceptional in attracting a continuous flow of migrants from far and wide. The larger provincial cities, such as Norwich and York, also provided opportunities for the more adventurous, but the majority of the population - even after the coming of the railways - did not venture beyond their nearest market towns. The 'core families' that stayed put for generation after generation and who had well-established connections with similar families within the neighbourhood were the ones that shaped the character of the place: its speech, customs, attitudes, forms of religion, styles of vernacular architecture, working practices, and all the other matters that cemented a local society. These links are not as strong as they were, but even today a surname can locate a person within the territory where it was formed several centuries ago.

Surnames also provide vital evidence for the movement of populations overseas, particularly across the Atlantic. They can suggest whereabouts in Britain a family originated and they can sometimes indicate that a group of neighbours went on the long voyage together or perhaps followed each other when the first adventurers reported the success of their journey and the rewarding prospects that lay ahead. Genetics has been highly successful in demonstrating the movement of human populations in prehistoric and early medieval times. In tracing the movements of people in recent centuries, it has the benefit of drawing on other methods of enquiry. The cooperation of scholars across the disciplines is a very welcome development in all such studies. It is clearly necessary for a true understanding of surnames.

Earliest Recorded References

"The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names" (1960) Eilert Ekwall at page 380

Ramsdale Ha [Ramesdala 1170 Oxf], Ramsdale - YN [Ram(m)esdal 1240 FF], Ramsden Bellhouse, Crays & Heath Ess [Ramesdana DB, -den 1158 BM, 1208 Cur, Ramesden Belhous, Gray 1254 Val, Ramesden Crei 1274 RH], Ramsden - O [Ramesdon 1179 RA, Rammesden 1279 RH, 1316 FA]. 'wild garlic valley' or possibly 'ram valley'. See HRAMSA, RAMM, DENU.

"The Place-Names of The North Riding of Yorkshire" (1979) A. H. Smith, Volume V at page 117

Fylingdales

FYLINGDALES 16 H 12

RAMSDALE

Ramesdale 1210 (Dugdale's Monasticon, 1817-1830, Volume iv. 319,) 1240 (Yorkshire Feet of Fines)

Rammesdale 1240 (Yorkshire Feet of Fines)

The early forms suggest that we have here OE hramse, ramese 'garlic, ramson' as in Ramsey (Hu), v. Björkman, Nordische Personennamen, 1910 Wo xli. Alternatively we may have OE ramm, hence either 'garlic valley' or 'ram's valley'.

Ramsdale farm in Nottinghamshire (EPNS Nt 114) was held by John de Ramsdale in 1332 - per Dr Gillian Fellows-Jensen (2 April 1997)

Ramsden Bellhouse was held by Ricardus de Belhous in 1208 (Cur). Bellhouse means "belfry". Ramsden Crays was held by Simon de Craye in 1252 (Cl). Craye is from CRAY or CRAYE in France.

Old English & Old Norse Derivations

OE hramsa, hramse, 'wild garlic', sometimes appearing as hramaes-, hremesin OE place name spellings and is therefore difficult to distinguish from rammes, genitive singular of ramm, as in (a) Ramsbottom La (botm), Ramsdale Ha (denu), Ramsey Ess, Hu (g), Ramsholt Sf (holt), Romsley sa, Wo 300 (leah) [Middle Low German ramese 'garlic']. [7]

The suffix -dale is derived from the OE doel, or, perhaps nearly always in old names, ON dalr, a dale, the root meaning being probably deep, low place [compare Gothic dalath, 'down']. Found from the Scottish border south to Derbyshire, but much commoner in the north, where Norse influence was strong, and there usually a river valley between hills, a glen - Allendale, Borrowdale, Ennerdale, etc. [2]

Similarly, the English surname Dale is a topographic name for someone who lived in a valley, ME dale (OE doel), reinforced in Northern England by the cognitive ON dalr, or habitation name from any of the numerous minor places named with this word. [1]

"English Place Names" (1996) Kenneth Cameron, The Bath Press, at pages 189 to 191

Of the numerous place-name elements denoting a valley, "valley" itself is very rare and vale, also a French loan-word into English, is infrequent … Dale on the other hand is common enough, particularly in Scandinavianised areas of the country, and sporadically elsewhere. OE dœl, modern dale meant 'pit, hollow', and the general view today is that it was really only in general use with the sense 'valley' due to the influence of the cognate Scandinavian word dalr which did mean 'valley'. It would appear, therefore, that it was only in late OE, for the most part, that doel denoted a 'valley'. The usual English word for this topographical feature was denu, modern dene … The widespread use of dale in later minor names and field-names must, it would seem, ultimately be the result of Scandinavian influence … in major place-names the occurrence of doel 'valley' is rare indeed and south of the Thames it is not found at all. In Devon, for example, Dalwood is not recorded before 1175 and is probably of post-Conquest origin, while the other dale-name in Devonshire is Dymsdale, in Alwington, first recorded in 1371. The editors of The Place-Names of Devon comment "As the element dale is otherwise unknown in Devon the name can hardly be of local origin". Indeed, there can be little doubt that Dymsdale is derived from the topographical surname Dymmyngesdale, that of a miner or miners from Derbyshire or Staffordshire impressed into work in the royal stanneries in the south-west, for which there is evidence certainly from 1295. A John Dymmyngesdale is actually mentioned in the 1371 document noted above. The surname itself is doubtless derived from a place-name such as Dimmin Dale in Taddington (DBY) or Dimsdale (STS), but unfortunately the first element has not yet been fully explained. Dale is found most frequently to the north of the River Mersey and River Humber but it also occurs as far south as NTH. Even in the north, however, it is comparatively rare in DUR and NBL, where Scandinavian influence is much less than in YKS, and it has been plausibly suggested that the degree of Scandinavian influence is crucial in the use of dale in the formation of place-names. Further because of "its wide currency as a term for 'valley' it often replaced the more usual OE denu". This has happened in the self-explanatory Deepdale (NTH), Oxendale (LAN) 'where oxen are found', Saxondale (NTH) 'valley of the Saxons', and Stavordale (SOM), the first element of which may mean 'stake'.

Dale has been added to a number of river-names like Airedale (WRY), Eskdale (CUL), Lonsdale (Lune, LAN), Ribblesdale (LAN), Swaledale (NRY), and Wharfedale (WRY). It is named from animals in Cowdale (DBY) and Kiddal (WRY) 'cows', Grisdale (WES) 'young pigs', and Withersdale (SFK) 'wether-sheep', from plants in Farndale (NRY) 'fern', Matterdale (CUL) 'madder', and Mosedale (CUL) 'moss', from a cross in Crossdale (CUL), a church in Kirkdale (LAN, NRY), and from a fortification in Borrowdale (CUL, WES). In the north-west the first element is sometimes a Scandinavian personal name as in Bannisdale (WES) from Bannandr, Belasdale (LAN) from Blesi, and Skelmersdale (LAN) from Skelmer, while Patric, an Irish name, is the first element of Patterdale (WES).

OE denu has been referred to as "the standard OE term for a main valley" and as such is widespread in this country. We have seen how it has sometimes been replaced by dale and in at least one name, Longdendale (DBY), the latter has been added to an original Langdene 'long valley'. Indeed, it has been shown that most valleys derived from denu are long and sinuous, and as Ann Cole notes that "denu is mostly used of long, narrow valleys with two moderately steep sides and a gentle gradient along most of their length".

Compare and contrast with the text of the 1977 edition below:

"English Place Names" (1977) Kenneth Cameron, The Bath Press at pages 179 & 180

Of the numerous place-name elements denoting a "valley", valley itself is rare, and vale, also a French loan-word occurs infrequently … Dale, on the other hand, is common enough, particularly in the Scandinavianized areas of the country and occasionally elsewhere. Recent research has suggested that Old English dœl "dale" was not a common place-name element, and that the subsequent increasing use of dale was due to the influence of the corresponding Old Norse dalr. The similarity of the two words often makes it impossible to be certain which of them is the source of particular names. But it is probably the English word in Silverdale (LAN) 'silver' from the colour of the rocks, the common Deepdale and Debdale (NTH) 'deep', Edale (DBY) 'land between streams', and Sterndale (DBY) 'stony'. A few contain an Old English term for animals, as in Cowdale (DBY), Kiddal (WRY) 'cows', and Withersdale (SFK) 'wether', and for a plant in Farndale (NRY) 'fern', but the first element could be either English or Scandinavian in Mosedale (CUL) 'moss' and Westerdale (NRY) 'western'. Dalr is, however, likely where the first element is a Scandinavian word, as in Borrowdale (Cu, We) literally "valley of the fortification", Bowderdale (CUL) "valley of the booth", Wasdale (CUL, WES) 'valley of the lake', Grisdale (WES), of which the first element means 'young pigs', Uldale (CUL) 'wolves', and probably Matterdale (CUL) 'where madder grows' and Birkdale (LAN) 'where birches grow'. This is similarly the case where the first element is a Scandinavian personal name, Bannandi in Bannisdale (WES), Blesi in Bleasdale (LAN), Skelmer in Skelmersdale (LAN), as well as Patric, an Irish name, in Patterdale (WES).

The usual Old English term for a valley was denu, as in Dene or Dean, common minor names in many southern counties, as well as the Sussex Eastdean and Westdean, originally simplex names later distinguished by East- and West-. In the North, however, this element is comparatively rare, but in some names it may later have been replaced by dale.

Teutonic Sources

Many old Norse names had roots and meanings similar to old English names, for the Saxons had themselves come as invaders from the opposite shores of the North Sea, like the Vikings. This makes it often impossible in their modern forms to distinguish between names which are in fact Viking from similar names which are Old English. [3]

Many names used by the Norman settlers after the Norman Conquest were also of Norse origin and indeed the name Norman itself simply means Northman. Some of these Norse names brought to England by the Normans are known to have been already used in England, for they occur in Saxon Charters, and other such names may also have been already used in England though they do not happen to survive in any of the Saxon charters which still remain to record the fact. Names of this kind became more common thanks to new arrivals with similar names from Normandy; but, whether used by conquerors or conquered, spelling and pronunciation took on the French air which was to be fashionable in conquered Anglo-Norman England for the next two centuries and more after 1066. [3]

The main source of English place names is Teutonic and came at two distinct times

- at the Anglo-Saxon invasions during the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries

- during the 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th centuries when the Danes came direct to this country from Denmark and the Norsemen or Northmen from Norway penetrated into the north-west by way of Ireland and the Hebrides, passing up the Wirral peninsular and spreading over Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire. [4]

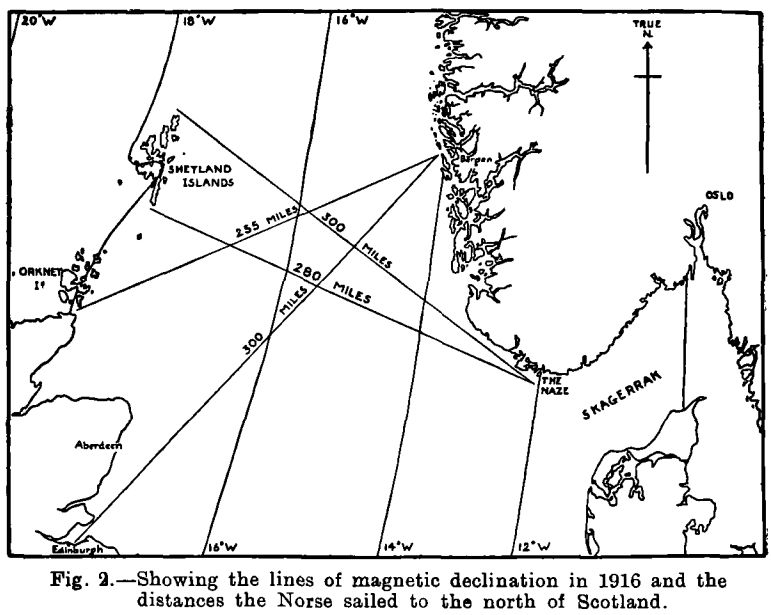

In addition to the direct invasion of England by the Danes via the east coast there was also a Norwegian conquest of northern Scotland, the Orkneys and Shetlands and other islands, as well as the over-running of most of Ireland. It was from the Hebrides and Ireland that they penetrated into England via the west coast, especially into Lancashire with an overflow into Yorkshire. Well over 50% of place names in Yorkshire are of Scandinavian as distinct from Anglo-Saxon origin. [4]

This double Teutonic influence has made it difficult in every case to say definitively to which source a place-name such as Ramsdale belongs, but if the root is to be found in Old English it will be allocated to the Anglo-Saxon period; if the root is to be found in Old Norse it will be placed in the period of the Danish and Norwegian invasions. Often, as perhaps in the case of Ramsdale, the root is to be found in both these old Teutonic languages (OE dæl and ON dalr), and then it is immaterial to which source we allot it. [4]

Professor Stenton, in an article published a recent number of the Historical Review, noted this Scandinavian influence in place name nomenclature in many ways, among them being … the frequent replacing of Old English names by Scandinavian, eg Scandinavian dalr replaced Old English denu, accounts for the large number of dales and the comparative rarity of deans or dens. But everywhere it is the Norse element that predominates, recalling the Scandinavian settlements of exceptional thoroughness in the 9th and 10th centuries. Remember that in 915 Norsemen from Ireland captured York, and for 35 years Irish Vikings ruled there. [4]

Viking Influence

In the same way that the Danish names in England are seen to radiate from the Wash, so the Norwegian immigration seems to have proceeded from Morecambe Bay and that part of the coast which lies opposite to the Isle of Man. [5]

In the North Riding, in the western half, in Gilling, Richmondshire and Langbargh, there is very definite evidence of extensive Norse settlement, as well as on the coast near Whitby, the latter, no doubt, reached directly from the North Sea. These Irish Vikings, on their way east, quickly came into contact with the earlier Danish settlers and in places there was a considerable mixture of races, Norwegian, Danish and Anglian. [6]

The Norwegian movement from the north-west into Yorkshire culminated in 919 in the capture of York by Ragnall mac Bicloch, who was the first of a series of Irish Viking Kings of York which lasted for 35 years, during which constant intercourse must have been maintained between Yorkshire and Ireland, with a constant increase of Irish-Norwegian settlers all along the route. [6]

Scarborough is one of the few place-names of which the exact origin is known. From the Kormaks saga we learn that two brothers Thorgils and Kormak went harrying in Ireland, Wales, England and Scotland: "They were the first men to set up the stronghold which is called Scarborough"

From two poems which Kormak addresses to his brother, we know that Thorgils was nicknamed Skarði, the hare lip, hence the Scandinavian form of the name, Skarðaborg, found also in English as Scartheborc circa 1200 later Scareburgh (1414). Thorgils died in 967; the brothers' expedition to England took place immediately after their return from one to Russia in 966, so that Scarborough must have been founded late in 966 or in 967. [6]

The mixture of races is well illustrated by such names as Danby, Normanby and Ingleby, each of which occurs three times in the North Riding. These denote villages of Danes, Norwegians and Angles and can have been given only by Scandinavians in districts where these races were in a minority. Normanby, found four times in Lincolnshire and three times in the North Riding, was a village where Norwegians lived, among an overwhelming Danish population.

"External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance" (2012) D. Gary Miller

Several places with the name Normanby in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire mark Norwegian settlements while Denby/Danby is Danish (Cameron 1958; Fellows Jensen 1972: 189ff, 1973: 18) …

In Norfolk, names in -by are rare except on the Norse-settled coast (Sandred 1987) …

-DAL(E). Valley names in -dal(e) (cf. OIcel dal-r 'valley: DALE') are frequent north of a line from the Mersey to the Humber, excluding Northumberland and Durham (PNL 95), e.g. Grisedale 'valley of pigs' (OIcel griss 'young pig: hog') …

The distribution of these names is interesting and unexpected. They provide evidence for Norwegians in the eastern Danelaw who could hardly be Vikings from Ireland. They may have been Norwegians who had joined the armies of Halfdan and Guthrun, and the scanty evidence of their presence in the eastern Midlands may be due to the known hostility between Danes and Norwegians. The capture of York from the Danes and the establishment of a Norwegian kingdom would not conduce to friendly relations, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the 10th century not only gives proof of the internecine feuds between them but also provides evidence of similar hostility farther south. [6]

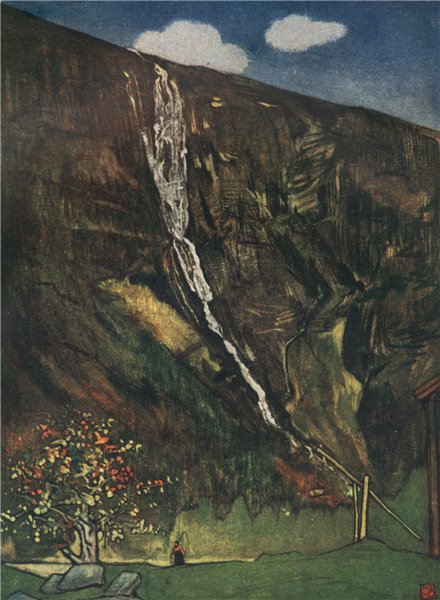

Norway, I. Virile Ways of the Modern Vikings" (circa 1920) A. MacCallum Scott Volume V at pages 3833 to 3845

Climate is an important factor in the development of racial characteristics. The North is a Spartan mother, and her sons are nourished in adversity and indurated to the struggle with nature. Fruits do not drop into their lap. They are trained to stand alone, compelled to exercise foresight. Like the pine that braves the tempest, their fibre is toughened by the struggle for life. The earliest members of the Gothic race to settle in Norway found in these sheltered fjords and narrow valleys and virgin forests plenty of food for those who had the skill and the strength to win it, and when their numbers had multiplied beyond the limits of their food resources they could send forth a breed of men able to find and take what they required elsewhere.

…

The coast of Norway is one vast sheltered harbour for thousands of miles. It is protected by a continuous belt of islands, large and small, the Skjaergaard, or fence of skerries, through the narrow straits between which ships wind their way as through a canal. Between these islands and the mainland there is a channel or belt of deep water, deeper than the outside ocean. The fjords are not river estuaries, but narrow, deep-sea channels, branching out in all directions until they almost meet, and penetrating sometimes one hundred miles into the interior of the country. Their towering cliffs run down precipitously into deep water.

The interior is a huddle of grey, rounded mountains culminating in the snow-clad heights of the Dovrefjeld and the Jotunfjeld, or Giant mountains. These are not peaked like the Alps. They have been ground down by glaciers, denuded, scraped, harrowed, by the ice plough of the Titans. Some relics of the Ice Age still remain in the shape of glaciers which feed the rivers that pour down the narrow valleys winding between the mountains.

Such a land, and such a coast, were essential for the breeding of such a race of seafarers as the Vikings. The Norwegians are a pure race, preserving all the characteristics of their Viking ancestors, and it is in the light of the Viking age that they should be studied.

Wheat is grown in the south, barley, rye, and oats farther north, but the corn supply has to be largely imported. The rearing of cattle, sheep, and horses is the staple occupation. The pastures are excellent. Among the most familiar features of the Norwegian landscape are the curious pegged posts, like hatracks, dotted over the fields, on which the hay and corn are dried, and the fences of rough wooden laths all slanting upwards.

Harvesting Barley in a Fertile Valley near Trondhjem

Barley makes a successful crop in South Trondhjem, and has been reaped six weeks after sowing, while records show that two crops a year are not uncommon. The ripe ears, cut down with the sickle, are bound into sheaves and stuck one above another to dry on poles, which at a distance look for all the world like rows of sturdy soldiers lined up for parade.

Drying Hay Crops in the Heart of the Norwegian Highlands

So damp is their climate that the Norwegian agriculturalists have considerable difficulty in drying the newly-cut hay; and to enable the air to reach the crop more readily, they erect long, fence-like structures, several feet high, on which the hay is stacked. Sometimes the hay is piled up on separate poles, as is done in the Swiss and Austrian Alps.

Bringing Home the Scanty Herbage Grown on the Heights

So thrifty and painstaking are the Norwegian farmers that every blade of grass on the steep hillsides is cherished for the use of the cattle during the long winter. Clipped and collected annually, these miniature mountain crops are sometimes transferred from their high altitudes to the valleys below by pulleys on long wires, and brought down the fjords to their destinations by boats.

All Hands to the Rakes in the Hay-making Season