- Robin Hood in the North: a Theory of a Norse Origin to the Legends, The Yorkshire Post, 16 January 1934 by Lewis Spence

- The Robin Hood Tradition: Further Speculations on its Origin, The Yorkshire Post, 24 January 1934 by W. L. Wilmshurst

- Thynghowe, Hanger Hill, Robin Hood's Larder, Budby (SK 59981 68372), The Friends of Thynghowe

- Robin Hood's Bay - Its History and Origins, Fylingdales Local History Group

- An Icelandic-English Dictionary - sources, Richard Cleasby & Gudbrand Vigfusson

- Robin Hood Place-Names, Robert Fortunaso

- Robin Hood bombshell as theory behind archer's final resting place blown open, Daily Express, 11 August 2020

- "The Secret Library", Oliver Tearle, 2016 at pages 56 to 58

- 'Reclaiming Robin Hood', Dan Eaton and Dr David Clarke, Daily Mail, 20 December 2021

- 'Robin Hood - the Facts and the Fiction'

- 'Reclaiming Robin Hood - Folklore & South Yorkshire's Infamous Outlaw', Dr David Clarke, Ron Clayton, Dan Eaton, Nigel Humberstone and Jo Wingate, (2021) The Sensoria Festival Ltd

- International Robin Hood Bibliography (place names)

Way Foot, Robin Hood's Bay

Robin Hood's Bay and Ravenscar

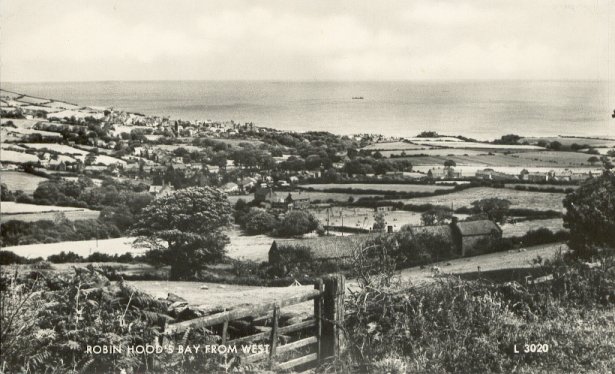

Robin Hood's Bay From The West

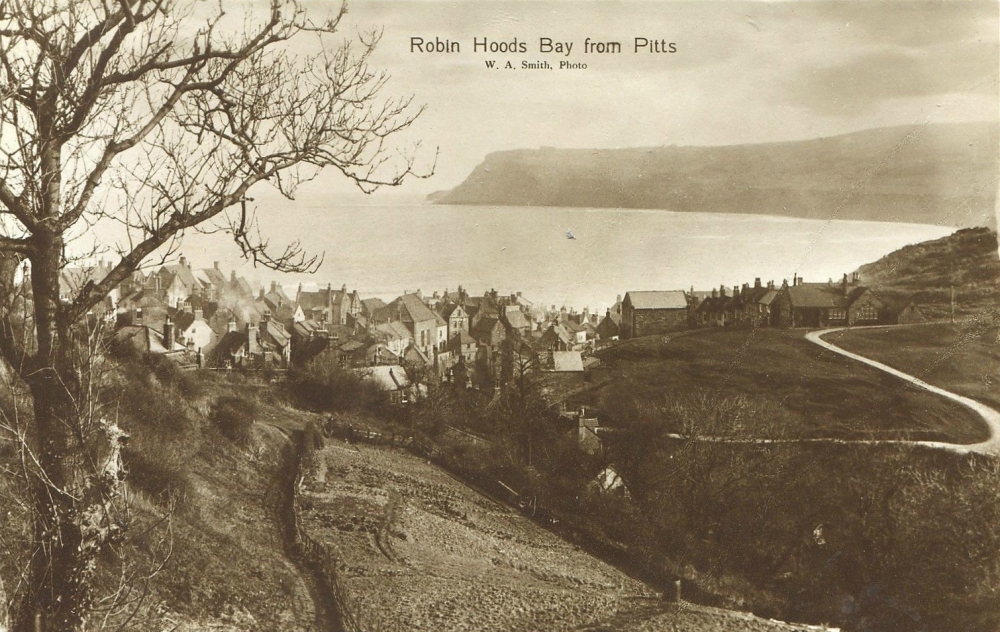

Robin Hood's Bay from Pitts

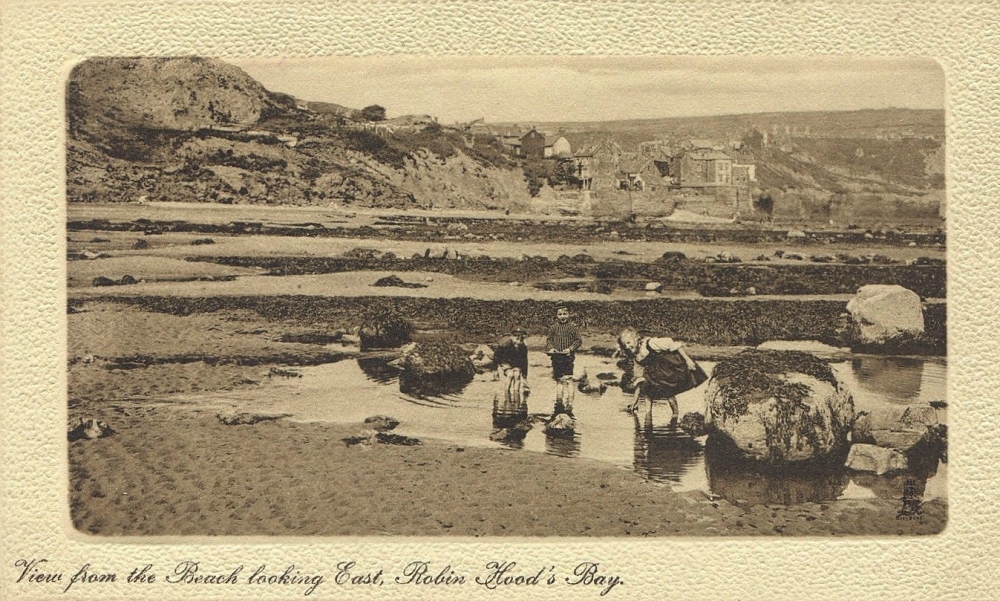

View from the Beach looking East, Robin Hood's Bay

Robin Hood's Bay from the south

Robin Hood's Bay from the south

|

|

| Low tide in Robin Hood's Bay. 1972 photographic images looking inland at the coast (a) south of Boggle Hole (right image) and (b) north of Boggle Hole (left image - the wooded cleft on the right), showing the wave cut platforms of rock. These layers of Jurassic rock are rich in fossils especially ammonites. The whole area is a site of special scientific interest where hammering of the bedrock is not permitted. | |

Robin Hood in the North: a Theory of a Norse Origin to the Legends (1934) by Lewis Spence

The Yorkshire Post, Tuesday 16 January at page 6

The adventures of bold Robin Hood and his merry men are by no means confined to Sherwood, nor are they even limited to English soil. It would indeed have been strange had the traditions of a figure of such outstanding mediaeval popularity failed to overflow into the neighbouring shire of York, when Northumbrian lore is full of his legends, and Scotland can boast of as many tales and ballads concerning him as of its own William Wallace, and can point to at least two localities as the grave of one of his followers.

The odd thing is that while notices of Robin Hood's appearances in Yorkshire are of comparatively late origin, those relating to his activities in North Britain are to be found among the early passages of Scottish literature. But as we shall see, good reasons exist for such a condition of things, and it is not at all necessary to invent a Scottish exile for the romantic outlaw, even though his "game and play" was so popular at Edinburgh as to cause the most serious annoyance to the Reformers so late as 1565.

Evidence in 1779

It is Charlton in his "History of Whitby and Whitby Abbey", published at York in 1779, who affords us the best modern view of the movements of Robin Hood in Yorkshire. He tells us that in the latter years of the twelfth century Robin "resided generally in Nottinghamshire or the southern parts of Yorkshire". But his robberies became so flagrant and the popular outcry against him so loud that the whole nation grew alarmed at last, and troops were despatched from London to apprehend him.

Unable to cope with the royal forces, the outlaw effected a retreat northward, crossing the moors which surrounded Whitby and gaining the sea-coast, where he provided himself with a number of small fishing vessels by which he could make his escape if necessary. The place where his boats were kept in residence was the spot still known as Robin Hood's Bay, in the waters of which he and his men indulged in fishing. In the neighbourhood he set up butts or marks, where his band practised archery, so that they might not grow rusty in the use of the long bow. But, adds Charlton, the site commonly attributed to these butts, when excavated in 1771, was found to have been a pagan burial-place, although it seems probable that Robin used the low tumuli which covered the graves as suitable eminences on which to place targets.

Stretching a Long Bow

It is in another "History of Whitby", that by the Rev. George Young, published in 1817, that a deed of superhuman might is attributed to this bandit as a part of local tradition. We are informed that Robin and his trusty henchman Little John went to dine with one of the abbots of Whitby, and being desired by the prelate to try how far each of them could shoot an arrow, they loosed their shafts from the top of the abbey. The arrows fell on the west side of Whitby Lathes, "beside the lane leading from thence to Stainsacre, that of Robin Hood falling on the north side of the lane, and that of Little John about a hundred feet farther on the south side of the lane."

In the spot where Robin's arrow is said to have lighted stands a stone pillar about a foot square and 4 feet high; and a similar pillar 24 feet high marks the place where John's arrow fell. The fields on the one side are called Robin Hood Closes, and those on the other Little John Closes.

Tradition inevitably describes Robin Hood as "Earl of Huntingdon". But the researches of Gough at the end of the eighteenth century made it clear that his earldom had a popular sanction only, and indeed was nothing more than a nickname. The period of Robin's supposed career is generally fixed as between the years 1160 and 1247, during which time Malcolm IV, William the Lyon, and Alexander II, kings of Scotland, were undoubted holders of the title successively. As is well known, David I of Scotland became Earl of Huntingdon in right of his wife Matilda, the widow of Simon de St. Liz Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon, and in 1127 did homage to Henry I of England in respect of this title. This, of course, accounts for the great popularity of Robin Hood in Scotland, where his legend was probably introduced by Scots who had heard it at Huntingdon.

But it is much more interesting to probe into the distant and possibly mythological origin of the famous forester than to speculate as to his nobility or lack of the same. Accurate historical notices of him are entirely wanting, and although it is not unlikely that the traditions respecting him may have become confused with the adventures of a veritable bandit who, with his followers, infested Sherwood Forest, many of the circumstances associated with them seem to point to a mythical origin for this romantic figure.

Norse Origin ?

In the first place his name is not a little suspect. Though usually spelt as "Hood", "Hude", or even "Whood", it is more rarely found as "Ood" and "Ooth". Now this may be only the old English "wod" or "wood", meaning "wild" and indeed Robin is surnamed "wild" by at least one ancient Scottish poet, while another alludes to him as "waith", that is "wild" or "wandering".

But it seems more probable to the writer that the name, especially in its forms of Ooth and Whood, has reference to Odin, Odhin, or Othin, the Allfather of Norse mythology the Anglo-Saxon form of whose name was Woden, and who was originally the wind which bloweth where it lists. For Woden was the old wind-god, associated in later legend with the wild huntsman, and from him the royal Saxon houses of Deira and Bernicia claimed descent, and Deira as everybody knows, was a territory practically co-extensive with Yorkshire.

Moreover, Odin was known to the later witchcraft of the northern counties as Hudikin, the prophetic familiar spirit. What more probable than that the cult and worship of the ancient god of the Angles and Danes of the North was, on the adoption of Christianity, forced to take refuge in the recesses of Sherwood, where legends of the deeds of its principal figures would remain for generations?

There is traditional evidence, too, that Robin, and his men were not regarded as persons of mortal bulk. Hector Boece, describing the grave of Little John "in Murray Land" says that he was fourteen feet in height and the limbs of his body in due proportion. Indeed the old chronicler claimed to have examined his haunch-bone, in the "mouth" of which, he says, he was able to place one of his arms!

Will Scarlet may, indeed, be a modern form of the name of Odin's brother Vill, and "Maid Marian" a corruption of Mardoll, one of the ancient names of Freya, his wife, while Allan-a-Dale might be equated with Ullr, the famous archer-god, who dwelt in the yew-forests, whence he procured the wood for his bows, and who took Odin's place when absent. In the course of ages the Norse pantheon, imprisoned in the green shadows of Sherwood, would emerge in the popular fancy as mere "foresters". beneficent to the descendants of those who had worshipped them, terrible to the Norman supplanters of their faith.

But one must not wander too far upon the sands of surmise, and this provisional reading or an ancient story clamours for the aid of further faithful research. The hypothesis, however, is given here for what it is worth, and local examination of records and place-names may effect much in its favour, or assist in its demolition.

The Robin Hood Tradition: Further Speculations on its Origin, The Yorkshire Post, Wednesday 24 January 1934

Sir, Mr. Lewis Spence's article in "The Yorkshire Post" of January 16 is of exceptional interest to students of local history and folklore. In it he suggests that the origin of the Robin Hood tradition is mythological and connected with the Norse religion which, as Yorkshire place-names show, flooded the county until Christian times, and in which Odin was the chief divinity. He puts his suggestions no higher than conjecture and as subject to correction, but they appear reasonable, and the following remarks, which also are offered tentatively, may help to support them and to explain the name of the town from which I write.

First, Yorkshire place-names testify to the wide diffusion in the county of the Scandinavian religion and the names of the gods of its pantheon. Wensleydale is Wotan's Dale, and appropriately contains Asgard (now Aysgarth), the Norse equivalent to the garden of Eden. Thor left his name at Thirsk, Thoralby, Thurstonland, and Thurgoland; Freia had her shrines at Fryston, Fridaythorpe and Frizinghall, each of these places having been a primitive religious centre. But the chief god Odin or Wotan, who, in Mr. Spence's submission, became anthropomorphised into Robin Hood, seems also to have provided Huddersfield with its name. Huddersfield is pretty certainly Hood's or Odin's field, and in local speech is still called "Hoodersfeld" or "Uthersfeld." Domesday Book gives it as Odersfeld Oder being a form of both Odin and Uther (who, by the way, was the demigod father of another legendary hero, King Arthur, or Ar-Thor); its site is usually regarded as having once been the property of a primitive landowner named Oder, whereas more probably it was the "field" (district or parish) of Odin worship; no doubt, too an important centre, since near the town are also found Woodsome (Hood's home), Woodhouse (Hood nawse, or ridge), and Woodhead (Hood's hill or headland), whilst Robin Hood's reputed grave is at Kirklees, near Mirfield, where once stood a Christian monastic house and probably a pagan altar before that. The Yorkshire tongue has twisted "hood" into "wood" as it converts "home" into "whom". And the Huddersfield district seems to be in respect of place-names more redolent of Robin Hood and Odinism than the Sherwood Forest, with which Robin is popularly associated.

The name Odin takes many other forms than Hood; it links up with the Irish "Aodh", the Hebrew letter "Yod" and the English "God" and even "Buddha" is an Eastern variant of Wotan; thus pointing to some primeval root-name for Deity which has undergone numerous local modifications. From Odin we also get the word "odd" as applied to a person who holds unusual views, and which was formerly "wood". "He is wood" occurs in Shakespeare, and means mad, fanatical; but earlier still it probably meant an Odin-worshipper, or as one might say, in the dialect, a "Hoodersfielder".

The Arthurian Legend

Next we have to account (as Mr. Spence partially does) for Odin worship becoming reduced and travestied into the legend of Robin Hood and his bandits. This is not difficult when we recall the parallel Arthurian legend, which is recognised as a solar myth re-expressed in terms of Christian chivalry. King Arthur and his knights impersonate a divine ruler and his officers governing the world (or round table). Similarly the legend of Robin Hood is myth expressed in terms of forestry and one appropriate to an uncivilised age when England was so densely wooded that, as Macaulay said, a monkey, swinging from tree to tree, might have travelled from Newcastle to London without touching ground.

Robin Hood was Odin writ small and personalised; his "merry men" correspond with Arthur's knights; they went about protecting the forest tribes from wild beasts, keeping the peace and redressing human ills. Later, in time, as the land became civilised, their beneficent activities became satirised as banditry and, with changes in religion, the old gods and saviours were regarded as reprobates and outlaws. In all religions one finds a chief god or demigod with a bevy of subordinates who execute his orders; even Christianity has its central Master and twelve apostles; so that, here again, we trace a common root idea underlying all religions, the more advanced ones taking over and reproducing the. main features of the earlier. One may go farther and suggest that in Little John, Robin Hood's favourite comrade, there is a possible equating with John, the "beloved disciple"; whilst pretty certainly Maid Marian is to be identified (like the Irish Brigit) with the Virgin Mary. Close to Robin Hood's reputed grave is Mirfield, which may be Mary's field, just as Prizinghall is "Freia's Ing" (or field), one of Freia's other names having been Mardoll.

Finally, Robin Hood's traditional feats of archery may well be due to the literalising of a religious idea. Divine influences, like the solar rays, are always found symbolised by arrows shot by the Sun-god (Ra or Apollo); even the Hebrew Psalmist praying for deliverance from his enemies uses the phrase "Shoot out thine arrows and destroy them". So when we find stones (as at Whitby, Kirklees, and elsewhere) indicating the places where Robin Hood's and Little John's arrows fell, we may reasonably infer them as marking the site of an ancient religious cult and associate them with such similar stones as the "Devil's Arrows" at Boroughbridge. Once they were pagan religious centres, but upon our country becoming Christianised these old stones came to be regarded as sinister and attributed to ancient powers of evil.

Yours, etc., W. L. Wilmshurst, Gledholt, Huddersfield, January 19

Thynghowe, Hanger Hill, Robin Hood's Larder, Budby (53.209041,-1.103361 & SK 5998168372)

An Icelandic-English Dictionary based on the manuscript collections of the Late Richard Cleasby, enlarged and completed by Gudbrand Vigfusson, M.A.

hangi, a, masculine, a law term, a body hanging on a gallows, Fornmanna Sögur v. 212: the mythological phrase, sitja, setjask undir hanga, to sit under a gallows, of Odin, in order to acquire wisdom or knowledge of the future; for this superstition see Ynglinga Saga ch. 7; whence Odin is called hanga-guð, hanga-dróttinn, hanga-týr, the god or lord of the hanged, Edda 14, 49, Lexicon Poëticum by Sveinbjörn Egilsson, 1860; varðat ek fróðr und forsum | fór ek aldregi at göldrum | … nam ek eigi Yggjar feng und hanga, I became not wise under waterfalls, I never dealt in witchcraft, I did not get the share of Odin (i.e. the poetical gift) under the gallows, i.e. I am no adept in poetry, Jómsvíkinga-drápa 3 (MS., left out in the printed edition). According to another and, as it seems, a truer and older myth, Odin himself was represented as hangi, hanging on the tree Ygg-drasil, and from the depths beneath taking up the hidden mystery of wisdom, Hává-mál 139; so it is possible that his nicknames refer to that; compare also the curious tale of the blind tailor in Grimm's Märchen, No. 107, which recalls to mind the heathen tale of the one-eyed Odin sitting under the gallows.

hangr, m. a hank, coil; það er hangr á því, there is a coil (difficulty) in the matter.

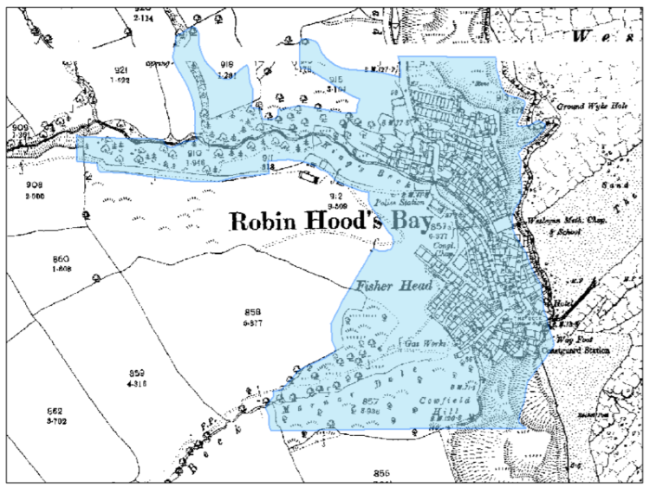

Robin Hood's Bay - Its History and Origins

Millions of years ago, the land upon which Robin Hood's Bay is situated was once a deep sea. The sea animals of the time, buried in the mud, became fossilised, providing one of the best sources in Britain for the fossil hunter. Some of these fossils can be seen on display in the museum and can still be picked up on the beach if you look carefully.

The scaurs (derived from a Norse word meaning 'rock') exposed at low tide, were formed 170 million years ago and consist of limestone and blue shale. A wealth of sea life can be found in the rock pools at low tide.

Robin Hood's Bay lies in the ancient parish of Fylingdales approximately 3 miles to the east of the hamlet of Ramsdale. The name itself is believed to be derived from the OE word 'Fygela' which meant 'marshy ground'. The first evidence of man in the area was 3000 years ago when Bronze Age burial grounds were dug on the high moorland a mile or so south of the village. These are known as Robin Hood's Butts. Some 1500 years later, Roman soldiers had a stone signal tower built at Ravenscar about the 4th century AD. The first regular settlers, however, were probably Saxon peasants, followed by the Norsemen. The main colonists of this coast were Norwegians who were probably attracted by the rich glacial soil and ample fish, and this is how they survived by a mixture of farming and fishing. The likely original settlement of the Norsemen was at Raw, a hamlet (like Ramsdale) slightly inland, which helped to avoid detection by other pirates.

After the Norman Conquest, the Manor of Fyling was given as the spoils of war to one of William the Conqueror's relatives, Hugh of Chester. Eventually, it passed to the Percy family who gave the land to Whitby Abbey.

The first recorded reference to Robin Hood's Bay was in 1536 by King Henry VIII's topographer, Leland, who described 'a fischer townelet of 20 bootes with Dok or Bosom of a mile yn length'. By now the cliff settlement had grown larger than the inland settlement, probably because they felt more secure from piracy and because it would be more convenient to walk from the boats. By 1540, the village was said to have fifty cottages by the shore (a large settlement at that time) so we can speculate that the present village originated somewhere in the 15th century. In 1540, the chief tenant was Matthew Storm and his descendants still live in the area. At the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539, the land passed to the King who sold it to the Earl of Warwick. The Cholmleys and then the Stricklands became the final 'Lords of the Manor'. It appears that in the 16th century, Robin Hood's Bay was far more important than Whitby. In a series of Dutch sea charts published in 1586, Robin Hood's Bay is indicated while Whitby is not even mentioned.

The actual origin of the name remains a mystery. There is not a scrap of evidence to suggest that Robin Hood of Sherwood Forest folklore visited the Bay. The name is more likely to have grown from legends with local origin and probably from more than one legend. Robin Hood was the name of an ancöient forest spirit similar to Robin Goodfellow and the use of the name for such an elf or spirit was widespread in the country. Many natural features were named after these local folk of legend and, in time, stories crossed over from one legend to another. The traditional anecdotes probably go way back in time but as to their origin - who knows?

What we are more certain of is that in the 18th century, Robin Hood's Bay was reportedly the busiest smuggling community on the Yorkshire coast. Its natural isolation, protected by marshy moorland on three sides, offered a natural aid to this well-organised business which, despite its dangers, must have paid better than fishing.

Smuggling at sea was backed up by many on land who were willing to finance and transport contraband. Fisherfolk, farmers clergy and gentry alike were all involved. Fierce battles ensued between smugglers and excise men, both at sea and on land, and Bay wives were known to pour boiling water over excise men from bedroom windows in the narrow alleyways. Hiding places, bolt holes and secret passages abounded. It is said that a bale of silk could pass from the bottom of the village to the top without leaving the houses.

The threat of the excise men was not the only danger to Bayfolk. In the late 18th century and early 19th century, the Press Gangs were feared and hated. Sailors and fishermen were supposed to be exempt but, in reality, rarely were. Once 'pressed', their chances of returning to their homes were not high. Village women would beat a drum to warn the men folk that the Press Gangs had arrived and it was not unusual for the Press Gang to be attacked and beaten off.

The fishing industry reached its zenith in the mid 19th century and a thriving community existed in Bay. The townsfolk liked to amuse themselves in the winter and there were dances almost every evening. Church and chapel were well attended and funerals and weddings were occasions for a festival. Like other fishing villages, Bay had its own gansey pattern. From the early 19th century, Robin Hood's Bay began to attract visitors from the outside and this has continued to the present day.

With grateful thanks to the Fylingdales Local History Group.

An Icelandic-English Dictionary - sources

The following sources are taken from An Icelandic-English Dictionary based on the manuscript collections of the Late Richard Cleasby enlarged and completed by Gudbrand Vigfusson, M.A.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 266, entry 48

HJÁLMR, m. [Gothic hilms; Anglo Saxon, English, Old High German, and German helm; Danish-Swedish hjalm; Italian elmo; Old French heaume; a Teutonic word probably derived from hylja, to hide]: - a helm, helmet; … 2. in the mythology Odin is called Hjálm-beri, a, m. helm-bearer, Grímnis-mál; he and the Valkyrias were represented as wearing helmets, Edda, Hákonar-mál. 9, Helga-kviða Hundingsbana. 1. 15; whence the poets call the helmet the hood of Odin (Hropts höttr): …

HÚFA, u, f., pronounced húa, [Scottish how; Old High German hûba; German haube; Danish hue] - a hood, cap, bonnet …

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 312, entry 19

HÖTTR, m., hattar, hetti, accusative plural höttu, a later form hattr, Droplaugar-sona Saga 13, Egils Saga. 407, Njála 32, 46, Gísla Saga 55, Ólafs Saga Helga Legendaria 46, as also in modern usage; [the Anglo Saxon hôd, English hood, Old High German huot, Dutch hoed, German hut may perhaps be identical; but Anglo Saxon hæt, English, Danish, and Swedish hat certainly answer to the old höttr, compare also hetta, quod vide] - a hood, in olden times only a cowl fastened to a cloak, as is seen from numerous instances … Odin is represented wearing a hött, and so the helmet is called the hood of Odin, etc.; as also Ála höttr: the vaulted sky is foldar höttr = earth's hood, Lexicon Poëticum by Sveinbjörn Egilsson, 1860: dular-höttr, huldar-höttr, a hiding hood, hood of disguise. hattar-maðr, m. a hooded man, man in disguise, Reykdæla Saga 272; Síð-höttr 'Deep-hood' was a favourite name of Odin from his travelling in disguise, compare Robin Hood. III. a proper name, Fornaldar Sögur.

"An Icelandic-English Dictionary" (1874 & 1957) Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson at page 287, entry 5

HROPTR, m. a mythical name of Odin, perhaps the crier, prophet (from hrópa), Grímnis-mál. 8, Kormak, Völuspá. 61, Loka-senna 45, Eyrbyggja Saga 78 (in a verse), Hús-drápa (Edda); properly an appellative, as seen from the compounds Rögna-hroptr, m. the crier of the gods, the prophet = Odin, Hává-mál 143; Hropta-týr, m. the crying god = Odin, Hává-mál 161, Grímnis-mál 54.

Editor's note: the forename Robert (Robin) could be derived from Hropta as the earliest written references are to 'Robert Hood' - see above "whence the poets call the helmet the hood of Odin (Hropts höttr)" or 'Robert Hood'.

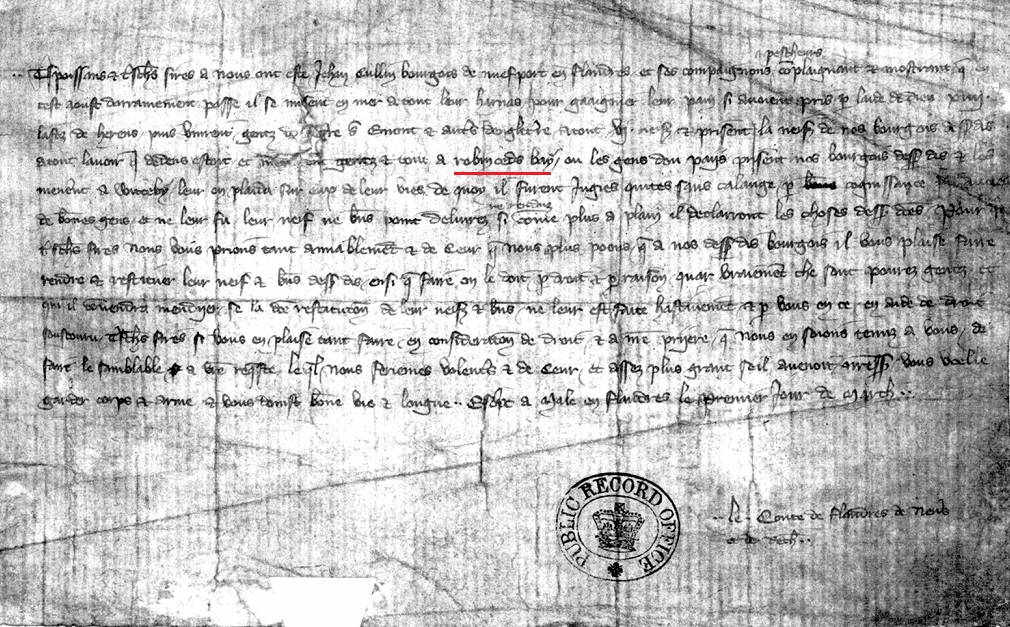

'Robin Oed's Bay' is mentioned in correspondence from the years 1324 to 1346, between the Count of Flanders and King Edward (Ancient Correspondence of the Chancery and the Exchequer, National Archives, SC1/33/202). The record was discovered by Robert Lynley. This place later became known as 'Robin Hood's Bay' (Yorkshire, North Riding).

'Robin Hood's Bay Letter'

See International Robin Hood Bibliography for a translation of the Robert Lynley letter.

NRY (10 place-names)

- Robin Hood: One mile north of Catterick Bridge. A small hamlet along the course of the old Great North Road or Roman Dere Street.

- Robin Hood's Bay: 12 miles north of Scarborough. A fishing village on the north side of the bay of the same name. One of the oldest and most intriguing of all Robin Hood place-names, in use by at least the early sixteenth century: see 'Robyn Hoodis Baye' in 1544, Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, XIX, i, p. 224; Leland's Itinerary, Toulmin Smith, I, 51; G. Young, History of Whitby, 1817, II, 647. The suggestion that the name was taken from a tumulus called 'Robbed Howe' near the neighbouring village of Sneaton is probably unlikely (V.C.H. Yorkshire, North Riding, II, 534). A place-name associated, but probably long after its formation, with the Robin Hood ballad of The Noble Fisherman. This place was named 'Robin Oed's Bay' in letters of correspondence between the Count of Flanders and King Edward from the years 1324 to 1346. The origins of the name are unknown.

- Robin Hood's Butts: two miles north of Danby. Three tumuli on Danby Low Moor and others further north of Gerrick Moor towards Skelton.

- Robin Hood's Butts: six miles west of Barnard Castle.

- Robin Hood's Butts: two miles south of Robin Hood's Bay. Three tumuli, about a mile from the sea and 775 feet above sea-level, south of a beacon at Stoupe Brow. They probably derive their name from Robin Hood's Bay which they overlook.

- Robin Hood's Howl: one mile west of Kirkbymoorside. Appears to be a hole or hollow on the southern escarpment of the North Yorkshire Moors: Ekwall, Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, 1960 edn., p. 254.

- Robin Hood and Little John Inn, Castleton: now probably the most famous of all inns named after Robin Hood. The building itself can be dated to 1671 on the evidence of the inscription on the lintel over the door; but no precise date can be given for the origins of the myth (still prevalent in Castleton) that Robin Hood and Little John met here for the last time.

- Robin Hood's Tower: Richmond Castle. An 11th century tower projecting from the curtain wall of Richmond Castle; probably named only after the 15th century.

- Robin Hood's Well: three miles south-west of Wensley. A well at the source of a hill stream on Melmerby Moor south of Wensleydale.

- Whitby: Robin Hood's Close and Little John's Close: two adjacent fields immediately west of Whitby Laithes, recorded as such in a land conveyance of 1713 (Young, History of Whitby, II, 647). They owed their names to two monoliths, one 4ft and the other 2½ft high, which stood at the side of the two fields, to the north of the lane that leads from Whitby Laithes to Stainsacre. These stones (a 'Robin Hood's Stone') occur as early as 1540: Cartularium Abbathiae de Whiteby, II, 727 and traditionally mark the points at which arrows shot by Robin Hood and Little John from the top of Whitby Abbey reached the ground: see L. Charlton, History of Whitby and Whitby Abbey (York, 1779), pp. 146-7; C. Platt, The Monastic Grange in Medieval England, 1969, p. 244; V.C.H. Yorkshire, North Riding, II, 506.

The medieval records of England provide us with a variety of thirteenth and fourteenth century persons of the surname Hood. Rather than being linked to Scandinavian or Germanic deities like Hodeken, Woden or Hodr, the surname could have originated from the English word for a head-covering; a Hood - Anglo Saxon hôd, English hood.

The most common mediæeval spellings are Hod and Hode, and there are also records of the surname Robynhod. Occasionaly the Robin Hood of legend is transformed into Robin Wood or Whood.

Robert was a common Christian name in post-Conquest England, and in the 13th century its alternative form of Robin was probably as common as Robert. It is suggested that the famous outlaw's name is an alias or nom de plume (e.g. John or Jane Doe), but there appears to be little evidence to support this theory.

Early references in the written record to 'Robin Hood'

- Circa 1191 - 1197 Robert de Huda (Pipe Rolls (7 consecutive entries) case of Morte de Ancestor)

- 1199 Robert de Hodelme (Curia Regis, had deserted Henry ll)

- 1200 Robert Hudde (Blythe Cartulary - swearing fealty)

- 1206 Robert Hod (Lincoln Assize Roll - disagreement between whose vassal he was)

- Circa 1213 - 1217 Robert Hod servant of the abbot of Cirencester, slew Ralf of Cirencester

- Circa 1220 - 1230 Robert Hod witness to land deed at Follifoot near Linton (Yorkshire Deeds)

- 1225 Robert Hod (Curia Regis Rolls, damage to a sheep holding at Shenle, Grange of Woburn Abbey, Buckinghamshire)

- Robert Hod of Yorkshire, fugitive in 1225. The name appears in the Yorkshire account in nine successive pipe rolls from 1226 to 1234, six times as Robert Hod, once (in 1229 - 30) as Robert Hood, and twice (in 1227 and 1228) as Hobbehod

- Circa 1230 Robert Hod witness to land deed in Worcester (Charters relating to the city of Worcester)

- 1234 Robert Hod Worcester, land dispute (Close Rolls)

- 1234 Robert Odde Somerset, land dispute (Curia Regis Rolls)

- 1237 Robert Hod accused of transgression, Devon (Curia Regis Rolls)

- Circa 1254 Robert Hod with others accused of a raid on the grange of Byland Abbey at Faldintun on Pilemor, Yorkshire

- Circa 1262 Robert Hod with others accused of taking goods at Hedon and Ottringham, Yorkshire

- Circa 1269 Robert Hod among the rebels at the Isle of Ely

- Circa late 1330s Robyn Hod appears on a garrison pay-roll of archers on the Isle of Wight

- Robert Hod imprisoned in 1354 for trespass of vert and venison in the forest of Rockingham

Robin Hood - the Facts and the Fiction

The following Robin Hood place-names (of YKS only), are a small selection of the vast number in English counties. This list focuses on names in England that appear in Ordnance Survey maps, and are arranged in alphabetical order. Many seem to have originated after 1800 and, of the others, the majority are first recorded in maps of the late eighteenth century.

Many English place-names also begin with the prefix 'Robin' such as the Robinswoods and Robinsgroves in SRY and ESS. Like the legend itself, Robin Hood place-names are not confined to England, they were undoubtedly exported to many other parts of the world by English colonists, particularly to Australia and the U.S.A.

It is surprising, given the popularity of the legend north of the border, that Robin Hood place-names are infrequent in Scotland. There is a concentration of names in YKS, DBY and NTT which shows us that the legend has kept its local associations for many years. There is a 'Robin Hod Hostel' mentioned in a subsidy roll of 1292 and a 'Robin Oed's Bay' in correspondence of the 14th century:

"Robin Oed's Bay is mentioned in correspondence from the years 1324 to 1346, between the Count of Flanders and King Edward (Ancient Correspondence of the Chancery and the Exchequer, National Archives, SC1/33/202). The record was discovered by Robert Lynley. This place later became known as 'Robin Hood's Bay' (see below; Yorkshire, North Riding, Robin Hood's Bay)."

York

Robin Hood Tower York city walls. The northern angle tower of the city wall, recorded in 1622 and 1629. The tower was called Bawing Tower in 1370 and Frost Tower in 1485.

Yorkshire, North Riding (North Yorkshire)

Robin Hood: One mile north of Catterick Bridge. A small hamlet along the course of the old Great North Road or Roman Dere Street.

Robin Hood's Bay: Twelve miles north of Scarborough. A fishing village on the north side of the bay of the same name. One of the oldest and most intriguing of all Robin Hood place-names, in use by at least the early sixteenth century: see 'Robyn Hoodis Baye' in 1544, Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, XIX, i, p. 224; Leland's Itinerary, Toulmin Smith, I, 51; G. Young, History of Whitby, 1817, II, 647. The suggestion that the name was taken from a tumulus called 'Robbed Howe' near the neighbouring village of Sneaton is probably unlikely (V.C.H. Yorkshire, North Riding, II, 534). A place-name associated, but probably long after its formation, with the Robin Hood ballad of The Noble Fisherman. This place was named 'Robin Oed's Bay' in letters of correspondence between the Count of Flanders and King Edward from the years 1324 to 1346. The origins of the name are unknown.

Robin Hood's Butts: Two miles north of Danby. Three tumuli on Danby Low Moor and others further north of Gerrick Moor towards Skelton.

Robin Hood's Butts: Six miles west of Barnard Castle.

Robin Hood's Butts: Two miles south of Robin Hood's Bay. Three tumuli, about a mile from the sea and 775 feet above sea-level, south of a beacon at Stoupe Brow. They probably derive their name from Robin Hood's Bay which they overlook. See Teesdale's 1828 Map of Yorkshire; Young, History of Whitby, II, 647.

Robin Hood's Howl: One mile west of Kirkbymoorside. Appears to be a hole or hollow on the southern escarpment of the North Yorkshire Moors: Ekwall, Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, 1960 edn., page 254.

Robin Hood and Little John Inn: Castleton. Now probably the most famous of all inns named after Robin Hood. The building itself can be dated to 1671 on the evidence of the inscription on the lintel over the door; but no precise date can be given for the origins of the myth (still prevalent in Castleton) that Robin Hood and Little John met here for the last time.

Robin Hood's Tower: Richmond Castle. An eleventh-century tower projecting from the curtain wall of Richmond Castle; probably named only after the fifteenth century.

Robin Hood's Well: Three miles southwest of Wensley. A well at the source of a hill stream on Melmerby Moor south of Wensleydale.

Whitby: Robin Hood's Close and Little John's Close: Two adjacent fields immediately west of Whitby Laithes, recorded as such in a land conveyance of 1713 (Young,History of Whitby, II, 647). They owed their names to two monoliths, one 4ft and the other 2½ ft high, which stood at the side of the two fields, to the north of the lane that leads from Whitby Laithes to Stainsacre. These stones (a 'Robin Hood's Stone' occurs as early as 1540: Cartularium Abbathiae de Whiteby, II, 727) traditionally mark the points at which arrows shot by Robin Hood and Little John from the top of Whitby Abbey reached the ground: see L. Charlton, History of Whitby and Whitby Abbey (York, 1779), pp. 146 - 7; C. Platt, The Monastic Grange in Medieval England, 1969, page 244; V.C.H. Yorkshire, North Riding, II, 506.

Yorkshire, West Riding (incorporating South Yorkshire)

Barnsdale: North of Doncaster (see Barnsdale and Sherwood) 'the wooddi and famose forest of Barnesdale, wher they say Robyn Hudde lyvid like an owtlaw' (Leland's Itinerary, ed. Toulmin Smith, IV, 13). An area of approximately four to five miles from both north to south and east to west between the river Went and the villages of Skelbrooke and Hampole, six miles north of Doncaster. Places in Barnsdale closely associated with the Robin Hood legend are:

- Barnsdale Bar: the place where the Great North Road forked into two branches, one leading through Pontefract and Wetherby to the extreme north, the other through Sherburn-in-Elmet to York.

- Bishop's Tree: the site of the tree by the side of the Great North Road where Robin Hood, according to tradition, intercepted the Bishop of Hereford. (Child 144).

- Robin Hood's Well (see below)

- Sayles Plantation: the site of 'the Saylis', southeast of the modern Wentbridge Viaduct, to which Little John is commanded to 'walke up' by Robin Hood at the beginning of the Gest.

- Wentbridge: the village at the bridge over the river Went mentioned in Robin Hood and the Potter.

Little John's Well: one mile northwest of Hampole. A stone well beside the Doncaster-Wakefield Road to the west of Barnsdale. It appears as 'Little John's Cave and Well' in an 1838 Tithe Award, and as 'Little John's Well' on the 1840 Ordnance Survey Map (P.N.S. West Yorkshire, II, 44). It is incised with Little John's name (see photograph in Mitchell, Haunts of Robin Hood, p. 4).

Loxley: three miles northwest of Sheffield. This Loxley is mentioned by Joseph Hunter: "the fairest pretensions to be the Locksley of our ballads, where was born the redoubtable Robin Hood." The remains of a house in which it was pretended he was born were formerly pointed out in a small wood (Bar Wood) … and a well near called 'Robin Hood's Well' (Hallamshire, London, 1819, page 3).

Robin Hood: four miles southeast of Leeds. This village is now skirted by the northern section of the M1 motorway. It appears on the 1841 Ordnance Survey Map.

Robin Hood's Bower and Moss: four miles north of Sheffield. The precise site of this place-name is apparently lost. It appears as 'Robin Hood's Bower, Bower Wood' near Ecclesfield in 1637.

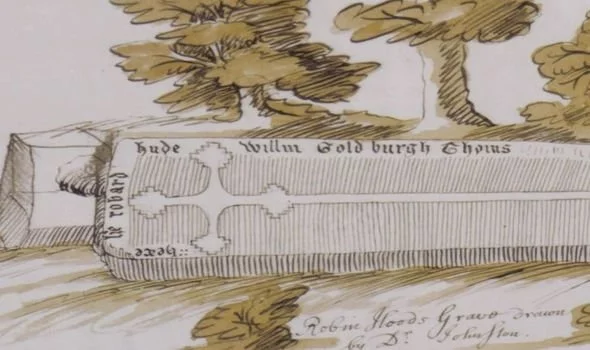

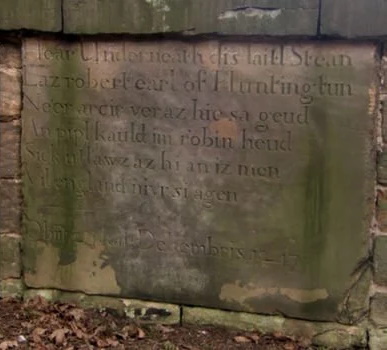

Robin Hood's Grave, Kirklees: four miles northeast of Huddersfield (see Robin Hood's Grave). The most enigmatic of all the places associated with Robin Hood. His supposed grave lies in a secluded part of the Kirklees Estate, 650 yards southwest of the ruins of the Cistercian nunnery where, according to legend, the outlaw is supposed to have met his death. Robin Hood's Cottage is in the vicinity.

Robin Hood Hill and House: one and a half miles south of Huddersfield. A hill and house at Berry Brow near Almondbury, south of Huddersfield. The local railway tunnel is called 'Robin Hood Tunnel'.

Robin Hood Hill: two miles north of Wakefield. A hill immediately west of the village of Outwood. It appears as 'Robinhoodstreteclose' in an unpublished Wakefield Court Roll of 1650 and as 'Robbin Hood hill' in 1657. Robin Hood House and Robin Hood Bridge are in the vicinity.

Robin Hood's Park: four miles southwest of Ripon. A name presumably applied to part of an estate near Fountains Abbey.

Robin Hood's Penny Stone: five miles northwest of Halifax. A rocking-stone on Midgley Moor in the Pennines, immediately northwest of Midgley. It appears in J. Watson's History and Antiquities of the parish of Halifax (London, 1775), page 27.

Robin Hood's Penny Stone: two miles west of Halifax.

Robin Hood's Stone: four miles southeast of Skipton. A stone near Silsden, southeast of Skipton. It appears in an 1846 Tithe Award.

Robin Hood's Well: six miles north of Doncaster. On the eastern side of the Great North Road, this well is in the middle of Barnsdale, and historically is probably the most significant of all the Robin Hood place-names. It appears to be near the site of a 'stone of Robin Hood' which was recorded in a Monkbretton charter of 1422. It is mentioned as 'Robbinhood-well' by Roger Dodsworth. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was one of the most famous halting-places on the Great North Road. The well-house, in the shape of a 'rustic dome' was designed by Vanbrough for the Earl of Carlisle in the early eighteenth century, it survives near its original location.(see Dobson and Taylor, pages 18 - 19; also Mitchell, Haunts of Robin Hood, pages 25 - 6).

Robin Hood's Well: one and a half miles north of Threshfield. A well near the road between Threshfield and Kilnsey in Wharfedale. It has been recorded as 'Robin Hood's Beck and Well'.

Robin Hood's Well: one and half miles north of Halton Gill. A well high on the Yorkshire Pennines north of Pen-y-ghent.

Robin Hood's Well (and Wood): Fountains Abbey. This well is associated with Friar Tuck's battle with, and ducking of, Robin Hood (see the ballad of Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar). It appears as 'Robin Hood Wood' in a Vyner land deed of 1734.

Robin Hood Well: five miles northwest of Sheffield. A well in Low Hall Wood, northwest of Ecclesfield. It appears as 'Robin Hood's Well' in 1773. It is possibly associated with 'Robin Hood's Bower and Moss' (see above).

Robin Hood Well: two miles west of Haworth, near the village of Stanbury in the Pennines.

This page contains information found in Rymes of Robyn Hood, Dobson and Taylor, pages 293 - 311.

Robin Hood bombshell as theory behind archer's final resting place blown open Daily Express 11th August 2020

ROBIN HOOD may not be buried where it is conventionally believed as expert analysis throws the debate wide open.

Robin Hood is one of English folklore's most prolific tales and describes an outlaw with god-like archery skills who helped starving populations by giving them supplies his band of Merry Men had stolen from the rich. The stories have inspired in excess of 250 film and TV adaptations - including one Disney animation and numerous celebrity incarnations - which began in the early nineties, along with songs, fables and sketches. While the anti-hero who roamed Sherwood Forest, in Nottingham, is known widely through pop-culture, there are few historical documents that account for his existence. But experts believe two of the earliest-known accounts to detail Robin Hood could give clues about the man behind the myth.

One such tale is 'A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode' - the names spelled in olde English variations - which ends with the hero being carried away for medical treatment by his right-hand man Little John. The document, which is one of the two oldest ballads to feature him, was penned in Middle English and is believed to have been printed between 1492 and 1534. Towards the end of the tale, Robin Hood was carried away to a nunnery named Kirklees Priory, in Yorkshire - the county the account claims he was from - for treatment of an injury.

Speaking on National Geographic documentary series 'Mystery Files', mediæval historian Graham Phillips said:

"Little John takes him there in the hope that he'll be cured by the abbess (the head of the abbey). But she betrays him and what she does is partly treat his wounds, when they used to have to have blood letting, she [then] bleeds him to death."

The building where he supposedly died was tracked down - it's there where the ballad claims Robin Hood fired his last arrow and instructed Little John to bury him wherever it fell.

|

|

|

| The former priory where Robin Hood supposedly fired his final arrow | Sketch of burial from 1600s shows Robert Hode was buried there | Grave with an inscription that hints that Robin Hood's burial may not be true |

Around 600 metres, a grave carries the name 'Robert Hode' - which some believe was where the final shot landed and the legendary archer was buried. Mr Phillips said:

"If you look at the inscription it has an olde English type inscription telling us that Robin Hood was buried here. But the problem is, this is clearly a stylised way in which 19th Century romantics thought that olde English was written."

After years of trailing through countless documents from the Middle Ages, he concluded:

"It's not genuine, it was put there in the 1800s. This date was several centuries after the timeframe Robin Hood was supposed to have lived - in the 13th or 14th Century. Not only that, it's believed that even a 'mediæval master bowman' could not have fired an arrow 600 metres - approximately the equivalent length of five or six football pitches."

Despite this, Mr Phillips claims the mistaken belief about where Robin Hood is interred may not have all been a sham. He said:

"There is evidence that there was a grave there before the current one was put there in the 1800s. In fact, as early as the 1600s people make reference to a grave being there."

A sketch of the earlier burial ground in 1665, which was later replaced by the fake tomb, also carried the name of 'Robert Hode' - which Mr Phillips may have an answer for. He said:

"On that grave it said 'Here lies Robert Hode' - Robin is actually a nickname for somebody called Robert and Hode is one of the old spellings of Hood. So yes we do know there was an early grave there belonging to a Robin Hood."

Robin Hood's Bay Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan (October 2017)

| Ordnance Survey maps, first (1842) and second editions (1862), Conservation Area in blue showing Marnar Dale and Marnar Dale Beck |

|

|

|

| First edition Ordnance Survey map (1842) | Second edition Ordnance Survey map (1892) showing little change |

Aerial view looking north of Robin Hood's Bay showing Marnar Dale in the (middle to left) foreground

"The Secret Library", Oliver Tearle, 2016 at pages 56 to 58

Robin of Barnsdale

Robin Hood makes his debut in writing in the late fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman, which is commonly attributed to William Langland, a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer. It was a timely moment for the outlaw to enter literature: English literature as we know it was starting to emerge, and the Peasants' Revolt - one leader of which, the priest John Ball, even quoted from Langland's poem - occurred in 1381, shortly after Robin Hood first appeared on the literary scene. It was a time when the social order of England was being challenged and feudalism was rapidly declining. The oldest surviving work of literature to detail Robin's adventures is the anonymous fifteenth-century ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode. The early printer Wynkyn de Worde helped to get some of the first Robin Hood tales into print, around fifty years later: by then, Robin Hood was well and truly part of the English literary landscape.

Editor: the word Gest in the title of the poem refers to an event or deed (from Latin res gestæ, 'things done'.)

It is one of the oldest surviving tales of Robin Hood, printed between 1492 and 1534, but shows every sign of having been put together from several already-existing tales. James Holt believes A Gest of Robyn Hode was written in approximately 1450.

It is a lengthy tale, consisting of eight fitts.

It is a ballad written in Middle English.

It is also a type of 'The Good Outlaw' tale, in which the hero of the story is an outlaw who commits actual crimes, but the outlaw is still supported by the people.

The hero in the tale has to challenge a corrupt system, which has committed wrongs against the hero, his family, and his friends.

As the outlaw, the individual has to depict certain characteristics, such as loyalty, courage, and cleverness, as well as be a victim of a corrupt legal or political system.

However, the outlaw committing the crimes shows he can outwit his opponent and show his moral integrity, but he cannot commit crimes for the sake of committing crimes.

Friar Tuck, the famous man of the cloth among Robin's merry men, was a real person in fifteenth-century England, whose original name was Robert Stafford.

But where exactly is Robin's landscape ? Why is Doncaster and Sheffield's airport named after Robin Hood, if the plucky outlaw lived in Nottinghamshire ? There are several reasons. First, the earliest stories which mention Robin Hood are set in Yorkshire, not Nottinghamshire. Robin Hood's original home was Barnsdale Forest, not Sherwood (and in any case, the majority of the remaining woodland of Sherwood Forest is actually in Yorkshire, not Nottinghamshire). A Gest, for instance, makes no mention of Sherwood Forest. A Gest is, however, our source of many of the familiar features of the Robin Hood story, and many of the characters - Little John, Will Scarlet, Much the Miller's Son - first appeared in this anonymous poem. Robin Hood's cloak was scarlet in some of the Robin Hood tales: one nineteenth-century poem, for instance, has Robin in scarlet while his men don the famous Lincoln green.

Nottingham, while we're at it, derives its name from Snotingaham, the original name for the Saxon settlement that stood on the site of the present city: Snot was the Saxon chieftain who settled there, and somewhere along the way the initial 'S' was dropped.

In the original Gest story, Robin's king wasn't the absent crusading Richard the Lionheart (reigned 1189-99) - A Gest refers to 'King Edward', not Richard or John, and this puts Robin Hood later in English history, some time after 1272 when Edward I ascended the throne.

The idea of Robin being an outlawed nobleman, Robin of Locksley, is far more recent: it derives from Sir Walter Scott's celebrated medieval romance Ivanhoe (1820). This novel has also been credited with helping to popularize medieval history for a generation of later writers and artists, among them Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites. More recently, Scott's novel provided the blockbuster 1991 movie starring Kevin Costner, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, with its source material for the character of Robin Hood (who is known throughout as 'Robin of Locksley'; Locksley, by the way, provides us with another Yorkshire connection, since Loxley is the name of a village and suburb of the city of Sheffield in South Yorkshire). Many people criticized Costner for playing Robin with an unashamedly American accent, but Alan Rickman himself appears to have remarked that the American accent was closer to twelfth-century Anglo-Saxon than modern British English is.

'Reclaiming Robin Hood', Dan Eaton and Dr. David Clarke, Daily Mail, 20 December 2021

Was Robin Hood a Yorkshireman? Teacher believes he has found legendary figure's birthplace behind a primary school playground

- Dan Eaton believes a stone and carved cross behind the playground of Loxely Primary School in Sheffield marks the birthplace of the legendary folk hero

- Hallamshire, now called Sheffield, has been named as the birthplace in legend

- Claims are part of a new book as part of a campaign to 'bring Robin home'

- It hasn't gone down well in Nottingham, which claims Hood as one of their own

A teacher claims to have found the birthplace of Robin Hood - and it would make him a Yorkshireman. Dan Eaton believes an ancient marker stone and carved cross he discovered behind the playground of Loxley Primary School in Sheffield marks the cottage where the legendary folk hero was born. His revelation is made in his book, Reclaiming Robin Hood, which is sponsored by Sheffield Council as part of a campaign to 'bring Robin home'.

Hallamshire - an old name for Sheffield - was mentioned in medieval legend as Robin's birthplace and ancient records have come to light stating the outlaw, Robin of Loxley, was born at Little Haggas Croft, Loxley, in around 1160.

Co-author Dr David Clarke, of Sheffield Hallam University, said:

"Loxley, in Hallamshire, was identified as Robin's birthplace in two historical sources that date from the early 17th century."

There are now calls for a statue depicting Robin as a young boy to be built in the suburb as part of Sheffield's increasingly popular Robin Hood tourist trail.

But the book hasn't gone down well in Nottingham, which has long claimed the outlaw as its own. Current Sheriff of Nottingham Merlita Bryan said:

"Robin Hood is as much from Sheffield as Jarvis Cocker is from Nottingham. Everyone knows his arch rival wasn't the Sheriff of Sheffield."

She added:

"We get it - Yorkshire wants a piece of the legendary action. We've had similar claims from Kent, Wales and elsewhere before, but really everyone knows that he was from Nottingham. But we're always happy for others to help spread the word about the world's favourite outlaw."

It has also been claimed the outlaw met his death around 1247 AD after leaving the safety of Sherwood Forest to be healed by nuns in Kirklees Priory in West Yorkshire. The Prioress was the mistress of one of Robin's enemies and is said to have slashed open one of his veins while pretending to treat him.

International Robin Hood Bibliography (place-names)

See North Riding of Yorkshire place-names.

"A systematic search for relevant field names in all tithe awards for North Riding townships was completed on 9 September 2020. Everything found in the course of this search has a page of its own in this section of IRHB. However, there is still a brief list of place-names to be added from early Ordnance Survey maps, 'The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire' (Smith, A.H. English Place-Name Society, vol. 5 Cambridge, 1928), and Dobson & Taylor's list of Robin Hood-related place-names - see Dobson, R. B., ed.; Taylor, J., ed. 'Rymes of Robyn Hood: an Introduction to the English Outlaw' (London, 1976), pp. 306-307."

To be completed …