Part 1 Index: Etymological & Teutonic Sources

- Derivation of the Surname RAMSDALE

- Etymology

- Teutonic Sources

- Viking Influence

- Danish or Norwegian Origin ?

- Topographical and Toponymic (habitation) Surnames

- Heraldry

- Notes

- Møre og Romsdal, Norway

- Romsdal to Ramsdale

Part 2 Index: Locative Sources

- Ramsdale Hamlet, Fylingdale's Parish, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, North Yorkshire

- Lilla Howe Bronze Age Barrow, North Yorkshire

- Wade's Causeway, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale & Ramsdell Chapelries, Hampshire

Part 3 Index: Danish or Norwegian Origin

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (published sources)

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (table of place-names)

- Viking Society Web Publications

- Molde Wind Roses

- "On dalr and holmr in the place-names of Britain", Dr. Gillian Fellows-Jensen

- "The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire", (1979) A. H. Smith, Volume V

- "Viking Age Yorkshire", (2014) Matthew Townend at pages 95 to 112 (this page)

Part 4 Index: General

- Fylingdales: Geographical and Historical Information (1890), Transcript of the entry for the Post Office, Professions and Trades in Bulmer's Directory of 1890

- Fylingdales Parish: Victoria County History (1923) A History of the County of York North Riding Volume 2, Pages 534 to 537

- Ramsdale Mill, Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire - Postcard Views (circa 1917 to 1958)

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Edwardian Postcards (1901 to 1915)

- Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890)

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, Bronze Age Stone Circle, Fylingdales Moor, North Yorkshire

- Robin Hood's Bay - published articles regarding its origin

- Ramsdale Family Register - Home Page

Fylingdales

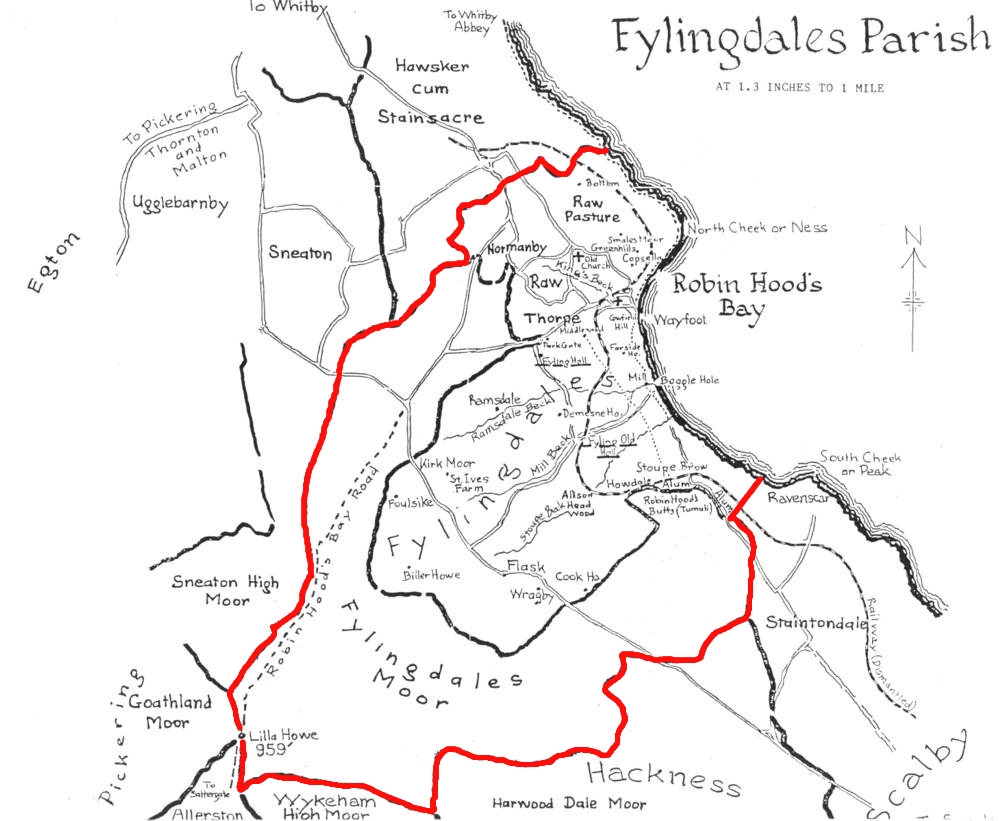

The area researched was originally confined to 'The Chapelry of Fylingdales' - see map above - first recorded as Figclinge in the 11th century, Figelinge and Fielinge in the 11th and 12th centuries and possibly as Saxeby in the 12th century. It was a parochial chapelry south of Whitby and contained the villages of Robin Hood's Bay and Thorpe, or Fylingthorpe (which was recorded as Prestethorpe in the 13th century) and the hamlets of Normanby, Parkgate, Ramsdale, Raw (Fyling Rawe, 16th century) and Stoupe Brow. Fylingdales Parish covers an area of 13,325 acres (53.92 km2, 20.82 miles2) of land and inland water.

The area researched was then extended beyond Fylingdales Parish to include 'The Liberty of Whitby Strand' comprising, in 1831, the parishes of Whitby, Hackness, Sneaton and the Chapelry of Fylingdales as taken from A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1923) at pages 502 to 505 (see map below) and which now includes the parishes of Aislaby (1865), Ruswarp (1870) and Hawsker (1878).

The area researched has been further extended to include (1) Pickering Lythe Wapentake, (2) Whitby Strand Wapentake and (3) Langbargh East Wapentake, described in "The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire" (1928) A. H. Smith, Volume V, at pages 74 to 157; in particular the littoral parishes comprising the North Yorkshire coast.

|

|

| England 878 AD | The Liberty of Whitby Strand |

North Yorkshire Littoral - Parishes |

|

Danish or Norwegian Origin ?

"Robin Hood's Bay lies in the ancient parish of Fylingdales. The name itself is believed to be derived from the Old English word 'Fygela' which meant 'marshy ground'. The first evidence of man in the area was 3000 years ago when Bronze Age burial grounds were dug on the high moorland a mile or so south of the village. These are known as Robin Hood's Butts. Some 1500 years later, Roman soldiers had a stone signal tower built at Ravenscar about the 4th century AD. The first regular settlers, however, were probably Saxon peasants, followed by the Norsemen. The main colonists of this coast were Norwegians who were probably attracted by the rich glacial soil and ample fish, and this is how they survived by a mixture of farming and fishing. The likely original settlement of the Norsemen was at Raw, a hamlet slightly inland, which helped to avoid detection by other pirates." See Robin Hood's Bay - its history and origins.

It is frequently impossible to decide whether a particular word or personal name is of Danish or Norwegian origin. However, place-names on the North Yorkshire coast ending in dale, by and thorpe are indicative of settlement by Norwegian adventurers in the 9th century AD who had joined Danish Vikings in subjugating the whole of northern England (the Danelaw) before settling there as farmers and traders and developing great mercantile cities such as York.

"It is only, I think, by comparison with other districts, and from the history of the old Danes and Norse - not merely as pirates, but as colonists - that we may hope to learn the facts and interpret the remains of the great Viking settlements." per "Norse Place-names in Wirral" (1896) W. G. Collingwood, Saga Book Vol. II at page 147

ON Origins: local place-name evidence

In the Pickering Lythe, Whitby Strand and Langbaurgh East Wapentakes there are some 8,731 examples of local place-names containing one or more of 502 ON original elements. Where a place-name has two or more ON original elements it is occasionally (but not always) included under both so the total number of examples includes some double, triple and quadruple counting. Examples of such multiple ON element listings are:

- Crook Ness, which appears under both krókr, 'crook' and nes, 'ness';

- Murk Mire Moor, which appears under myrkr, 'murk'; mýrr, 'mire'; mór, 'moor';

- Marnar Dale Beck, which appears under marr 'sea, fen, marsh'; ná, nær, 'nigh, near'; dalr, 'dale, valley'; bekkr, 'brook, stream';

In this regard see place-name element raw: hrar, bráð 'raw flesh' and rauðr 'red' with (seven) duplicate entries.

The table of local place-names can be found in Part 4 of "Derivation of the Surname RAMSDALE".

Old Norse is the language of Norway in the period circa 750 to 1350 (after which Norwegian changes considerably) and of Iceland from the settlement (circa 870) to the Reformation (circa 1550 - a date that sets a cultural rather than a linguistic boundary). Known in modern Icelandic as Norræna, in Norwegian as Norrønt and in English sometimes as West Norse or Old Icelandic, this type of speech is a western variety of Scandinavian.

Although Icelandic circa 870 to 1550 and Norwegian circa 750 to 1350 are here given the designation 'Old Norse', it would be wrong to think of this language as entirely uniform, without variation in time or space. The form of Scandinavian spoken in Norway around 750 differed in a number of important respects from that spoken around 1350, and by the latter date the Norwegian carried to Iceland by the original settlers had begun to diverge from the mother tongue. Nevertheless, in the period circa 1150 to 1350, when the great mediæval literature of Iceland and Norway was created, there existed an essential unity of language in the western Scandinavian world.

Old English is the name given to the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th to 11th centuries.

Basic Pronunciation of Old Norse

To keep the pronunciation guide accessible during your research, click on to load the guide in a pop-up window in the top left of your screen and use one of the following three methods to access the guide:

- toggle the alt + tab keys

- install AutoHotkey and activate the 'window always on top' script by placing the cursor in the pop-up window and pressing ctrl + spacebar

- install WindowTop (v3.4.5) and activate the 'window set on top' script by placing the cursor in the pop-up window and pressing alt + z.

Once WindowTop is installed you can set a window to sit on top of all others by moving your mouse to the window's title bar, then hovering over the small down arrow that appears (this is typically in the centre of the title bar, but we've found it sometimes appears at one side). Next, click the Set Top button (second from the left, with a red window - see screenshot below). This window will now stay on top of all others until you click the Set Top button a second time.

To make the window semi-transparent, return to the WindowTop controls. Click the Opacity button (far left), then move the slider accordingly. If you tick the 'Enable click-through' box, you'll be able to click through to the window that's under the one you've set to be on top. If you find WindowTop's controls too fiddly (the buttons are quite small), you can use its shortcut keys instead. To set the active window to be on top, press alt+z (press this a second time to return the window to normal). You can set multiple windows to be on top. If you've done this and want to return everything to how it was, right-click the WindowTop icon in the system tray at the bottom-right of the desktop (you may need to click the small up arrow to reveal the icon), then click Disable "Set Top" for all windows. To see (and customise) shortcuts for other controls, select the Hotkeys (Click to change) option.

| Vowels | |||

| á | as in father | ár | 'year' |

| a | the same sound, but short | dagr | 'day' |

| é | as in été, but longer | él | 'storm' |

| e | as in été | ben | 'wound' |

| í | as in eat | lítr | 'looks' |

| i | the same sound, but short | litr | 'colour' |

| ó | as in eau, but longer | sól | 'sun' |

| o | as in eau | hof | 'temple' |

| ú | as in bouche, but longer | hús | 'house' |

| u | as in bouche | sumar | 'summer' |

| ý | as in rue, but longer | kýr | 'cow' |

| y | as in rue | yfir | 'over' |

| æ | as in pat, but longer | sær | 'sea' |

| œ | as in feu, but longer | œrr | 'mad' |

| ø | as in feu | døkkr | 'dark' |

| ö | as in feu | björk | 'birch' |

| ǫ | as in naught | öl | 'ale' |

| Unstressed Vowels | |||

| a | as stressed a | leysa | 'release' |

| i | as in city | máni | 'moon' |

| u | as in wood | eyru | 'ears' |

| Diphthongs | |||

| au | as in now | lauss | 'loose' |

| ei | as in bay | bein | 'bone' |

| ey | ON e + y | hey | 'hay' |

| Consonants | |||

| b | as in buy | bíta | 'bite' |

| bb | the same sound, but long | gabb | 'mockery' |

| c | as in keep | köttr | 'cat' |

| d | as in day | dómr | 'judgement' |

| dd | the same sound, but long | oddr | 'point' |

| f | (1) as in far | fé | 'money' |

| f | (2) as in very | haf | 'ocean' |

| ff | as in far, but long | offr | 'offering' |

| g | (1) as in goal | gefa | 'give' |

| g | (2) as in loch | lágt | 'low' |

| g | (3) as in loch, but voiced | eiga | 'own' |

| gg | (1) as in goal, but long | egg | 'edge' |

| gg | (2) as in loch | gløggt | 'clear' |

| h | as in have | horn | 'horn' |

| j | as in year | jafn | 'even' |

| k | as in call | köttr | 'cat' |

| kk | the same sound, but long | ekki | 'nothing' |

| l | as in leaf | nál | 'needle' |

| ll | the same sound, but long | hellir | 'cave' |

| m | as in home | frami | 'boldness' |

| mm | the same sound, but long | frammi | 'in front' |

| n | (1) as in sin | hrinda | 'push' |

| n | (2) as in sing | hringr | 'ring' |

| nn | as in sin, but long | steinn | 'stone' |

| p | as in happy | œpa | 'shout' |

| pp | the same sound, but long | heppinn | 'lucky' |

| r | rolled | gøra | 'do' |

| rr | the same sound, but long | verri | 'worse' |

| s | as in this | reisa | 'raise' |

| ss | the same sound, but long | áss | 'beam' |

| t | as in boat | tönn | 'tooth' |

| tt | the same sound, but long | nótt | 'night' |

| v | as in win | vera | 'to be' |

| þ | as in thin | þing | 'assembly' |

| ð | as in this | jörð | 'earth' |

| x | as in lochs | øx | 'axe' |

| z | as in bits | góz | 'property' |

"Viking Age Yorkshire" (2014) Matthew Townend at pages 95 to 112

Evidence for Settlement III: Place-Names

Notwithstanding this remarkable, and ever-expanding, corpus of metalwork, it is, arguably, place-names that offer us our most extensive and important information about the nature and extent of Scandinavian settlement in the north and east of England: in Margaret Gelling's celebrated phrase, place-names act as 'signposts to the past'. In short, the influence of the old Norse language on Yorkshire place-names is immense - as also, of course, on place-names in Lincolnshire and other parts of the Danelaw. This place-name evidence has been much discussed, with debate being at times heated, and a number of reviews of the scholarship are available. The traditional interpretation of the place-name evidence, which will largely be accepted here, is that it suggests strongly that a large number of Norse speakers settled in Yorkshire in the ninth and tenth centuries.

Some scholars have, however, queried the interpretation that large numbers of Scandinavian place-names (and Scandinavian-influenced place-names) must indicate large numbers of Scandinavian settlers. So before we can proceed to a discussion of some of the main categories of Norse place-names in Yorkshire, the main objections to the standard interpretation of the place-name evidence should be considered.

Objection 1: could it be that the native Anglo-Saxons learned to speak Old Norse, so that many Norse place-names were given by Anglo-Saxons rather than Scandinavians ?

Old Norse and Old English were similar languages - indeed, in some ways they were more like different dialects than different languages - and it is highly likely that, at least for pragmatic purposes of communication, Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians could understand one another when each spoke their own language. This is not to say that some individuals may not have gained an active competence in the other language, but there is no evidence one can point to from Viking Age England for the use of interpreters, or for widespread bilingualism among one or both speech communities. Nor does one language seem to have enjoyed much greater prestige than the other. All this suggests that a model in which a large number of Anglo-Saxons, in the ninth and tenth centuries, switched to using Old Norse, as either a first or second language, is not likely to be correct. However, it is the case that gradually, over time, the Norse language ceased to be spoken in England, presumably as a result of a range of factors, such as inter-marriage and cultural erosion; and the demise of the Norse language will be discussed more fully later in this book. In Yorkshire this is most likely to have happened in the eleventh century, and as a result a large number of Norse words (and Norse pronunciations) passed into the English language. So place-names (especially minor names) which arose in the twelfth century or later, and which show Norse vocabulary or pronunciation (for example, minor stream-names in beck), should probably not be attributed to a Norse-speaking population. But nor do they indicate Anglo-Saxons speaking Norse during the Viking Age: rather, they testify to the profound influence which the Norse language had on English in the area, an influence which is best explained as a consequence of heavy Scandinavian settlement in the earlier period.

The next possible objection is related to the first, but pertains to personal names rather than language in general.

Objection 2: could it be that Anglo-Saxons adopted Norse personal names, so that place-names containing Norse personal names need not indicate Scandinavian settlement ?

In other words, should we hesitate to interpret place-names such as Haxby [NR] and Slingsby [NR] ('Hákr's farm' and 'Slengr's farm') as indicating the habitation or possession of a Scandinavian: might Hákr and Slengr have been Anglo-Saxons whose parents gave them Norse names ? The assumption behind this objection is that practices of name-giving in Viking Age England were much like those in twenty-first-century Britain, so that the popularity of different names, and different types of name, fluctuated according to fashion, and parents felt at liberty to give any names they chose to their children. But this assumption is almost certainly misplaced, as customs of name-giving in the medieval (and early modern) world were profoundly different from those in contemporary Britain. Rather than being a free choice, and subject to the fluctuations of fashion, Anglo-Saxon and Viking name-giving seems to have been governed and constrained by family ties and other close connections (such as god-parenting): children were normally named after a relative or patron, so that a widespread decision on the part of Anglo-Saxon parents to throw off family names and networks, and to choose new-fangled Scandinavian names for their children, seems highly unlikely. Nor is there much empirical evidence to support such a suggestion: it is very hard to point to examples of Anglo-Saxon families where Norse names suddenly make an appearance without inter-marriage or other close affiliation." This is not to deny that Norse names may sometimes have been given to children without Scandinavian connections; but it is unlikely that this was a significant factor in the appearance of a large number of Norse personal names in Viking Age Yorkshire.

Even if one grants that it was mostly Scandinavians who used Old Norse, and that Norse personal names usually indicate people of Scandinavian ancestry or affiliation, a further objection to the standard interpretation of the place-name evidence is still possible.

Objection 3: might the large number of Norse place-names be attributable to a small elite, rather than a large number of settlers ?

In some respects this is a variant, or even a combination, of Objections 1 and 2. In recent decades 'elite emulation' (or 'elite transfer') has often been appealed to, in historical and (especially) archaeological debates, as a way of accounting for cultural changes without invoking the idea of invasion or migration. As an explanation for certain events and developments in the early medieval world, particularly in terms of material culture, it is no doubt compelling, but elite emulation is unpersuasive as the primary motivation for Scandinavian place-names in England. For one thing, language is not the same as material culture, and does not operate and evolve according to the same rules, so the extension of what is fundamentally an archaeological model to historical linguistics may be problematic!' Nor does the meagre burial evidence from Viking Age England give us much encouragement for postulating widespread Anglo-Saxon emulation of a Scandinavian elite. More specifically, as we have just seen, the linguistic and onomastic results of Viking Age contact are not plausibly explained by the supposed cause of emulation - whether one thinks of that emulation in terms of Anglo-Saxons adopting the Old Norse language, or adopting Old Norse personal names, or somehow accepting and replicating Old Norse place-names (and place-name patterns) handed down de haut en bas. Historical linguists have demonstrated that the linguistic impact of Norse in England is hard to explain by reference to a small number of elite speakers: the influence of Old Norse on the English language, in terms of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, is too substantial for this to have been the case! The same is true of the Norse impact on place-names in England: their number, diversity, and vitality is too great to be attributed to only a limited body of Norse language-users, as we will see more fully when we review some of these place-names below.

Although the Norman Conquest may come to mind as a possible parallel in support of this objection, it does not, in fact, supply a persuasive comparison. The Norman elite did indeed make up only a small minority of the post-Conquest population in England; but their influence on English place-names was in fact modest, and on minor names it was insignificant. The French language did of course supply a great quantity of words to English in the later Middle Ages: but this linguistic transfer was on the whole restricted to vocabulary (grammar was untouched), and in many respects it was as much a consequence of the Europe-wide cultural prestige of French in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as it was a direct result of the Norman Conquest.

Furthermore, there is a great contrast between the occurrence of Norse personal names in England and, later, that of Norman names (and related Biblical and saints' names). The sheer range of Norse personal names attested in Viking Age England indicates that what we are dealing with is a vibrant, living tradition of name-giving, and not simply a closed corpus, limited in number and lacking in evolution. New permutations of Norse names, unattested in Scandinavia itself, arose in northern and eastern England - of female names as well as male names. While Norman and Biblical names did come to dominate name-giving in England in the later Middle Ages (at the time of the rise of hereditary surnames), the repertoire of Norman names recorded is many times smaller than the vast corpus of Norse names a few centuries earlier: in other words, it is the number of different Norse names that is significant, even more than the number of different people bearing Norse names. This suggests a very sizeable population of families giving their children Norse names, using, as it were, a language and grammar of name-giving of which they themselves are 'native speakers'.

As can been seen, then, while all of the objections raised against the standard interpretation of the place-name evidence have some coherence to them, they are unlikely to be fundamentally correct as the main means of explaining - or explaining away - Scandinavian place-names in England. The place-name (and personal name) evidence suggests a great number of Norse speakers in the area of the Danelaw, which suggests in turn a very sizeable migration during the settlement period. What 'very sizeable' means is, of course, extremely hard to say, and we should certainly not imagine that the Scandinavian settlers formed any sort of majority over the pre-resident Anglo-Saxons. But it is worth remembering that at exactly the same time when Halfdan was sharing out Northumbria among his followers, Scandinavian migrants were also making their way to Iceland, a considerably less fertile, less hospitable, and less accessible destination. It has been estimated that something in the order of 10-20,000 migrants made the journey to Iceland, and that within a few decades this population had expanded to perhaps 60-80,000. One would not, on the face of it, expect fewer migrants to have travelled to England than to Iceland, though estimates of the number of Norse migrants must remain only that - estimates, and highly speculative ones too.

But how far do the Old Norse place-names in England represent the establishment of new settlements and the colonization of new land, how far simply the re-naming of older settlements and estates - albeit by a sizeable Norse-speaking population ? As we will see below, the evidence suggests elements of both processes, but something should be said in general terms to begin with. One feature of pre-Viking England seems to have been the existence of large or multi-vill estates, sometimes termed 'multiple estates': large possessions with a caput or estate-centre which was serviced and supported by surrounding and tributary estates. Much of the evidence for supposed multiple estates is late (with Domesday Book often the earliest source for their reconstruction), and the model as a whole has been criticized on the grounds that some of its assumptions are nonfalsifiable. Nonetheless, it is generally agreed that the Scandinavian conquest of northern England did see the break-up of many or most of the large estates that may have existed (whether or not they fully matched the 'multiple estate' model), estates which had previously been in the control of the church, or the crown, or the aristocracy. Such large estates were broken up, and parcelled out, into smaller units, often in private ownership rather than strict dependence - a development which can be subsumed under the broader label of 'manorialization', an important process in the late Anglo-Saxon landscape.' Scholars who have taken a minimalist view of Scandinavian settlement in England have often pointed to this fragmentation of estates as the fundamental mechanism by which Scandinavian place-names arose, and have attributed them (in Glanville Jones' words) to 'a small number of privileged newcomers who were allowed by their leader to impose a degree of intermediate authority over old established hamlets'. As discussed above, the place-name material does not really allow for such a minimization of numbers - as the historian Patrick Wormald wrote, 'a mere change of landlords will not account for all the evidence', and one might in any case wonder whether the peasantry really would stay put when their lords had been driven off and their estates plundered - but nonetheless it is important to bear in mind this model of the break-up of estates as one of the basic processes by which land passed into Scandinavian hands in Viking Age England.

It is also clear that this Viking Age privatization of land-holding led to a market in the buying and selling of land, as testified by a number of tenth-century charters. Such a market is also implied in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's account of the dispersal of the 896 army (partly quoted above): 'the Danish army divided, one force going into East Anglia and one into Northumbria; and those that were moneyless [feohlease] got themselves ships and went across the sea to the Seine'. By the 890s, then, it seems that new arrivals in the Danelaw, if they did not possess family or lordly connections, required capital to buy themselves into land. Two northern hoards of the 870s, from Gainford [Durham] and Lower Dunsforth [WR], may well represent the feoh of members of Halfdan's army: these relatively modest hoards are composed exclusively of Anglo-Saxon silver pennies from south of the Humber (four at Gainford, and fifteen, or possibly more, at Lower Dunsforth), and it makes more sense to see these as imported Viking possessions than as the wealth of native Northumbrians.

The break-up of large estates need not involve the colonization of new land - though it may do so - but it may well lead to new settlements, functioning as the centres of the new, smaller, independent estates, and generally 'filling in' the occupied landscape. Moreover, while it is now doubted whether there was much 'virgin' land going spare in Viking Age England, land that had never previously been cultivated, it is certainly possible that one consequence of Scandinavian settlement was an intensification of land-working, with a return to cultivation of some land which had perhaps been farmed in the Romano-British period, but had reverted since then to non-cultivation. As Margaret Gelling has pointed out, 'virgin' land is an unhelpful term in this discussion, and 'disused' or 'under-exploited' would be better: the issue is not whether or not an area of land had ever been cultivated before the arrival of the Vikings, but rather whether it was being intensively cultivated at the time. We should not, however, discount the possibility of some genuinely virgin land being cleared for occupation: place-names in þveit 'clearing' would be an obvious group of names to consider, though there is not such a quantity of these to be found in Yorkshire as there is in Cumbria. In the course of the two centuries after the Norman Conquest, a better recorded period, it has been calculated that the amount of arable land under cultivation in England increased by 35%, through changes in agricultural practice, intensification of land-use, and an associated 'drive to the margins'; and there is good evidence that such processes were in train from the ninth century on-wards.

We can now turn from the general to the particular, and review the main types of Old Norse place-names in Yorkshire. In terms of settlement names, there are three main categories: names in -tun, names in -by, and names in -thorp. A fourth category would be miscellaneous settlement names not falling into any of the previous three. Of course, it is not the case that we can correlate Scandinavian settlement with Norse place-names in any simple, one-to-one fashion, as if Scandinavians only lived in places with Old Norse names and Anglo-Saxons in places with Old English names; that is not likely to be how it happened, though place-names that incorporate personal names are indeed likely to indicate the habitation or possession of a specific individual.

The Old English word tūn ('estate, settlement') was an important and productive place-name element in the mid and later Anglo-Saxon period, denoting a settlement or estate of some consequence. We find that the first element of Old English tūn names is often an adjective or noun (for example Weston 'west tun' [WR], or Poppleton 'pebble tun' [WR]), but sometimes a personal name (for example, Ebberston 'Eadbriht's tun' [NR]); the assumption is that the person commemorated in the name was a significant occupier or possessor of the estate, perhaps its first recipient when it was granted out by the king. As a result of the Scandinavian conquest of the north, this second type seems to have increased very greatly in frequency, with an Old Norse personal name being the first element (for example, Staxton 'Stakkr's tun' [ER] and Towton 'Tófi's tun' [WR]), and this group of names has traditionally been labelled 'Grimston hybrids' in the scholarship on Scandinavian place-names: 'Grimston' because Grímr is a common Old Norse personal name occurring in these names, and 'hybrids' because the names have been construed as a combination of an Old Norse personal name and an Old English generic (tūn). These 'Grimston hybrids' are important, and more will be said about them in a moment.

We also find, though less frequently, tun-names with an Old Norse word as their first element (or specific): for example, Brayton 'broad tun' [WR], Carlton 'peasants' tun' [WR], and (Cold) Coniston 'king's tun' [WR]. In the great majority of cases, the Old Norse specific, or defining element, has a corresponding (cognate) word in the Old English language, and so the usual assumption is that this group of names, which have been labelled 'Carlton hybrids', are originally Old English names which have been Scandinavianized in their first element by the adaptation to, or substitution of, the cognate Old Norse word. So, it is hypothesized, the Old Norse first element breiðr ('broad') in Brayton was originally Old English brād, karl in Carlton was Old English ceorl, konungr in Coniston was Old English cyning, and so on.

If we were to take the Carltons as our guide, then the obvious conclusion would be that the Grimstons were also, originally, Old English names in -tūn, in which Old Norse substitution or adaptation has occurred in the first element; and this has been the common view of these names. There are a number of problems with this view, however. One is that a defining feature of the Carltons is that the Old Norse specific was (probably) cognate with the preceding Old English specific, but this cannot have been the case for the Grimstons, where the specific is an Old Norse personal name. And a more fundamental problem with the customary interpretation has been pointed out by David Parsons, which is how odd it would be if only Old English settlement names in -tūn should have been treated in this way (that is, with the substitution of an Old Norse personal name in the first element) and not other classes of Old English settlement name, such as those in -hām. There are no 'Grimsham' hybrids, as it were, and what this suggests is that the Grimstons may not after all be adaptations of pre-existing Old English names in -tūn; rather, they may be wholly new names (albeit for pre-existing settlements), with tūn having been adopted into the Norse place-name lexicon with a meaning of 'English village or estate' (or more fully, 'English village or estate transferred into the possession of a new, Scandinavian lord'). This would mean that the Grimstons, linguistically speaking, are wholly Old Norse names, and not in fact 'hybrids', with one element from Norse and one from English.

Regardless of these linguistic niceties, it remains the case that the Grimstons are the most likely category of name to indicate the Scandinavian take-over of English villages and estates. This take-over should primarily be thought of at the level of lordship - it does not mean that all the English residents and workers were driven out - though of course it is important to remember that an elite male is not likely to have settled on his own, as the only Dane in the village. As the better-documented settlement of Iceland indicates, and other migrations as well, elite males are likely to have brought with them a household of relatives and dependents, and perhaps also to have stimulated side-by-side settlement by other members of their kin-group. That the great majority of Grimstons were pre-existing English settlements, and not new developments in the Viking Age, is indicated by a number of varied factors, all of which suggest a prosperous and well-established site: for example, their position on fertile soils, the frequency with which they became parishes, their relative wealth in Domesday Book, and their low rate of depopulation and desertion in the later Middle Ages.

An obvious question is whose name is preserved as the first element in the Grimstons. Were Stakkr, Tófi, and the rest, the first Scandinavian recipients of these settlements ? Does the corpus of Grimstons give us, in effect, a muster-roll for the officers of Halfdan's army ? There is little external evidence that can cast light on this question, to confirm whether these names and settlements should be dated to the 870s, or to a later period, though it has been demonstrated that personal name types that develop after 1000 are not normally found in Scandinavian settlement names in England. A possible counter-indication may be the small number of tuns where the personal name in the first element corresponds to the name of the person recorded in Domesday Book as possessing the estate in 1066. If such tuns are not eleventh-century settlements - thus indicating the longevity of tun as a place-name-forming element - then this might suggest that the personal names in such place-names were unstable, and liable to replacement as possessor succeeded possessor. But the fact that this group of names is so small (relative to the enormous quantity of tuns recorded in Domesday Book) must indicate, in fact, that such replacement was exceptional rather than the norm, and indeed it cannot even be certain that the person named in Domesday Book and the person commemorated in the place-name were one and the same: since the elite of Anglo-Saxon England were very often named after their ancestors, it may possibly be an ancestor of the 1066 tenant who is commemorated in the place-name. There is only one possible Domesday example in this category from Yorkshire: in 1066 land at Stainton [East Staincliffe wapentake, WR] was held by a man named Steinn, but this may well be a coincidence. Stainton is a common Danelaw place-name (there are at least a dozen examples), which arose through the Scandinavianization of an originally Old English stān-tūn ('stone settlement', so possibly 'quarry'); in other words, the name is probably a Carlton hybrid and not a Grimston. In terms of historical identification, a more intriguing and persuasive case, in that it features an unusual personal name, is that of Toulston [WR], 'Toglauss' tūn'. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that an earl with that name was killed in a battle at Tempsford in Bedfordshire in 917: some connection with the person commemorated in the place-name is plausible, though it may perhaps be a relative or descendant rather than the same person. A further possibility is a connection between the Skurfa killed at the Battle of Tettenhall in 910 and Scruton [NR], 'Skurfa's tun', but the same personal name also occurs in the place-name Sheraton [Durham], and so this may be less likely, unless one imagines the same man holding both estates.

On probability, the Scandinavians named in the Grimstons were most likely the early recipients of the estates after the Viking conquest. What the analogue of Iceland suggests (where we have the twelfth- or thirteenth-century Landnárnabók, or Book of Settlements) is that settlement names are likely to be named after - or at least, at a later period were thought to be named after - the very individuals who founded or first occupied the settlement. This is no more than one would expect, of course, though a speculative permutation for some of the Grimstons might be that the name preserved is not always that of the Scandinavian founding father of 876, but sometimes that of a re-founding father - perhaps the lord who oversaw a village's transformation into a planned, nucleated settlement, or who built a new church.

In her standard study, Gillian Fellows-Jensen counts 42 Grimstons in Yorkshire that are recorded in Domesday Book. These are widely distributed across the more fertile parts of the county, and with fewer in the West Riding than in the North and East. They also preserve a wide variety of Norse personal names, as follows (with the names being those suggested by Fellows-Jensen in her 1972 survey):

North Riding

- Burneston (Brýningr)

- Burniston (Brýningr)

- Catton (Káti or Katti)

- Foston (Fótr)

- Fryton (Friði)

- Garriston (Gjarðarr)

- Grimston (Grímr)

- Kirby Sigston (Siggr)

- Moulton (Múli)

- Nawton (Nagli)

- Oulston (Ulfr)

- Scruton (Skurfa)

- Wigginton (Víkingr)

- Youlton (Jóli)

- Þurulfestun [lost] (Þórulfr)

East Riding

- Low Catton (Káti or Katti)

- Flixton (Flík or Flikkr)

- Folkton (Folki)

- Foston on the Wolds (Fótr)

- Fostun [lost] (Fótr)

- Ganton (Galmr)

- Grimston (Grímr)

- Grimston Garth (Grímr)

- Hanging Grimston (Grímr)

- Hilston (Hildulfr)

- Muston (Músi)

- Nafferton (Náttfari)

- North Grimston (Grímr)

- Rowlston (Róðulfr or Rólfr)

- Ruston Parva (Róarr)

- Scampston (Skammr or Skammel)

- Staxton (Stakkr)

West Riding

- Barkston (Börkr)

- Brotherton (Bróðir)

- Fewston (Fótr)

- Flockton (Flóki)

- Grimston (Grímr)

- Royston (Róarr)

- Saxton (Saxi)

- Thurlstone (Þórulfr)

- Toulston (Toglauss)

- Towton (Tófi)

Of course, alternative explanations for some of these are possible (for example, the first element of Brotherton might be the common noun 'brother' rather than the name Bróðir, or the personal name in Garriston might be Gerðr or Gyrðr). There are also other candidates that might be added to the list, such as Flaxton and Claxton [both NR], two settlements north-east of York, close to the find-spot of the Bossall/Flaxton hoard: the etymology of Flaxton might be either 'flax settlement' or 'Flak's settlement', while Claxton appears as Claxtorp ('Klakkr's thorp') in Domesday Book, but as Claxton ('Klakkr's tun') in all later sources. It is also to be suspected that 'Grimston' itself is a generic name, indicating a poorer quality settlement, rather than that there was an unusually large number of Scandinavian settlers called Grímr. But in spite of the inevitable uncertainties, Fellows-Jensen's count is likely to give us a broadly reliable figure.

On the whole, as has been said, the Grimstons indicate prosperous settlements, so we should certainly point to them as being, as a category, among the places occupied or owned by the Scandinavian rural or landed elite. But the count of 42 Grimstons (or thereabouts) in Yorkshire is in fact quite a modest number (out of the total number of Old Norse place-names in the county), and it suggests that, in Yorkshire, we should not assume that English estates taken over by Scandinavians are confined only to those bearing Grimston names. That this is the case may be further suggested by the evidence of stone sculpture (a body of material which will be discussed more fully in subsequent chapters). The early tenth century, as we will see, saw a remarkable renaissance of stone sculpture in northern England, as many crosses and other monuments were erected in new, Scandinavian styles, presumably for new, Scandinavian patrons. But quite a lot of these sculptures are to be found in villages (in churches) which have Old English rather than Old Norse names - Middleton, with its famous warrior crosses, would be a good example. Forty years ago, Gillian Fellows-Jensen calculated that (according to the sculptures known at the time of her research) some 96 settlements existed in which sculptures in a Scandinavian style had been preserved: of these, 58 of the settlements bore English or British names, 15 bore pre-existing English or British names which had been Scandinavianized in some way, and only 23 bore names which were purely Scandinavian.

Before we proceed to interpretation of these figures, a few methodological reflections are required. First, we should heed the warning that in place-name studies it is the general patterns that are important, rather than individual examples; we cannot use the distribution of English and Scandinavian names simply on a case-by-case basis, to say that Scandinavians settled at this site but not at that. Second, and similarly, we should recognize that, in any individual case, we cannot be certain that the patron of a particular monument was of Scandinavian origin - though it would seem extreme to deny the validity of the general paradigm. And third, we should note that it is not possible, chronologically, to correlate or calibrate finely the production of the sculpture and the coining of the Grimston names, though a suggested dating bracket for both between the late ninth century and early tenth would not be controversial. Nonetheless, and in spite of these qualifications, what the co-plotting of settlement names and Viking Age sculpture does seem to suggest, as a general principle at least, is that the early tenth-century Scandinavian elite was not confined to settlements bearing Scandinavian names; otherwise, one would have to argue that, for some unknown reason, settlements with continuing English names were excepted from the division of Northumbria by Halfdan and subsequent rulers, and remained in the possession of an English elite - an assumption which would also transgress the principle that one should not identify settlements as English or Norse simply according to the language of their name. Moreover, the sculptures tend to be found in prosperous and high-status settlements (which is just what one would expect, as the patronage of sculpture was a costly business) - settlements on a par with the wealth and status of the Grimstons. All this combines to suggest, then, that while the Grimstons do indeed represent the category of place-names best indicative of elite Scandinavian take-over, this take-over was not restricted to settlements now bearing Grimston names. Why some settlements should have been re-named and not others is an interesting question, though in some cases medieval forms reveal that, while a settlement boasting Viking Age sculpture may be known by an English name in the present day, a Scandinavianized variant of the name was in fact current in the Middle Ages (so, for example, Stonegrave [NR] is recorded in Domesday Book in both an English and a Scandinavian form, Stan- and Stein-). Since we only know of linguistic forms from documentary evidence (from the eleventh century and later), and since such documents are written in English or Latin but not in Norse, we may in any case suspect that our textual sources under-report the frequency of Scandinavian place-names, and especially of Scandinavianized variants of originally English names.

The next category of names we must consider are those in -by 'farmstead, settlement, village'. These are much more numerous in Yorkshire than the Grimstons: no fewer than 210 by-names are recorded in Domesday Book for Yorkshire, plus another 69 in later sources. They are found most densely in the Vale of York and the North Riding. Linguistically, the composition of Yorkshire's by-names is very interesting: Gillian Fellows-Jensen calculated that the ratio of Old Norse first elements to Old English was 92:8; and where a personal name forms the first element (which is the case in over half the examples), the Old Norse to Old English ratio rises further to 94:6. The by-names thus boast an impressive cast of Scandinavian occupiers and owners, such as:

- Ásgautr (Osgodby [ER])

- Áslákr (Aislaby [NR])

- Brandr (Brandsby [NR])

- Dragmáll (Dromonby [NR])

- Eymundr (Amotherby [NR])

- Feitr (Faceby [NR])

- Helgi (Hellaby [WR])

- Ormr (Ormesby [NR])

- Rauðr (Roxby [NR])

- Róðmundr (Romanby [NR])

- Styrr (Stearsby [NR])

- Uglubárðr (Ugglebarnby [NR])

- Þóraldr (Thoralby [NR])

- and Þormóðr (Thormanby [NR])

and a few of the personal names are female, such as Gunnhildr (Gunby [ER)) and Hjalp (Helperby [NB)). There is also a healthy range of Old Norse words (appellatives) recorded as the first element of those by-names that do not include a personal name, for example:

- brunnr 'stream, spring' (Burnby [ER])

- ferja 'ferry' (North Ferriby [ER])

- kona 'woman' (Whenby [NR])

- kvern (Quarmby [WR])

- lundr 'copse' (Lumby [WR])

- malmr 'sandy field' (Melmerby [Halikeld wapentake, NR])

- mikill 'great' (Mickleby [NR])

- skítr 'dung' (Skidby [ER])

- skógr 'wood' (Skewsby [NR])

- veðr 'wether-sheep' (Wetherby [WR])

- and øfri 'upper' (Earby [WR])

So the by-names demonstrate lexical and anthroponymic variety in their first elements. (The recurrent combination kirkja + by 'church by', will be discussed in the next chapter.)

What is more, some by-names preserve traces of diagnostically Old Norse grammatical inflexions, such as the genitive singular -ar preserved in Bellerby [NR] ('Belgr's by') and Helperby [NR] ('Hjalp's by'). The conclusion, therefore, must be that the by-names 'arose in a predominantly Norse-speaking environmene. Lesley Abrams and David Parsons further observe, in their incisive review of these names, that settlements with by-names are typically less prosperous, and of lower status, than those with tun-names (both Grimstons and 'English' tuns, as it were), and therefore that 'they are unlikely on the whole to represent either the takeover of thriving English villages or the spoils seized by members of a (small, elite) conquering army'. The by-names thus appear to give us evidence of substantial Scandinavian settlement at a level somewhat lower than that represented by the Grimstons and comparable settlements.

A very difficult question to answer, though, is whether, as a class, by-names indicate new settlements or not. The answer, probably, is that some do and some don't. A number of the bys, like the tuns, are evidently new or alternative Norse names for pre-existing English settlements (most famously, Whitby [NR] was earlier Streoneshalh), and in a few cases there is even variation between by and tun in the early forms (for example, Coniston [ER] ('king's tun') is recorded as Coningesbi in Domesday Book). But the element is not fundamentally a synonym for tun, and instead it is used frequently for isolated or dispersed settlements. Some of these, perhaps even many, may well be new places with new names, and the likelihood is that the by-names cover a variety of settlement histories, including the transfer of established estates, the break-up of old estates and the 'manorial' creation of new, smaller estates, and even, possibly, the opening-up of uncultivated land.

In some ways it is easier to appreciate the characteristics of the bys if we contrast them with the thorps. There are just over 150 thorps in Yorkshire in Domesday Book. Again, over half of the examples have a personal name as their first element, and the proportion of Old Norse personal names to Old English is 90:10. Thorps have always been recognized as being, on the whole, lesser settlements than other place-name types, including tuns and bys: they often exist in simplex form (that is, the place-name is just 'Thorpe'), they have a high frequency of desertion in the later Middle Ages, and they have rarely grown into major settlements. A recent study of thorp-names in England, by Paul Cullen, Richard Jones, and David Parsons, has, however, made some startling, but nonetheless persuasive, claims as to what may have been distinctive and defining features of thorps in the early Middle Ages. In the 1960s and early 1970s Kenneth Cameron, in an influential series of studies, argued that both bys and thorps were likely to be new settlements on new sites, and thus evidence for the ways in which the Scandinavian settlers colonized previously uncultivated land (or, we should say, under-exploited land); and he proposed that, as the bys were on better soil than the thorps, the thorps were likely to be secondary, dependent settlements. Cullen, Jones, and Parsons have, however, turned Cameron's formulation on its head: modern soil taxonomies suggest that, on the whole, thorps occupy superior sites to bys, not inferior ones, and that, furthermore, the characteristic soils on which the two place-name types are found are contrastive and complementary: the thorps tend to be sited on soils more suitable for arable farming, the bys on soils more suitable for livestock. It may be for this reason that thorps are especially prominent in the East Riding, and bys in the North Riding. On top of this, there is usually a difference in the settlement morphology of the two sites (that is, in the typical shapes they assume in terms of street lay-out and so on): thorps tend to be compact, nucleated settlements (and thus, ostensibly, deliberately planned), whereas bys are more often dispersed and 'polyfocal' (and thus, ostensibly, of more organic growth). The conclusions to which such findings point are clear: many thorps appear to have been planned settlements for the purposes of arable farming, usually dependent on a more important manorial centre, and possibly linked with the revolutionary development of open-field farming that seems to have begun in the ninth century. Bys, on the other hand, are not likely to have had quite such a unity of purpose or genesis, though they may often have had an association with livestock farming rather than arable. The great place-name scholar Eilert Ekwall, for example, believed that the by-names represented settlements occupied not by one but by several Scandinavian settlers and their households - an assumption that accords well with the dispersed nature of many of the bys. Other scholars have also argued for a correlation, under certain circumstances, between Scandinavian immigration and dispersed settlement.

We should hesitate, though, to see the origins of the thorps, let alone the innovation of open-field farming, as a singularly Scandinavian achievement. Although there is little or no archaeological evidence for thorps being any older than 850 at the earliest, and most seem to have grown up, very rapidly, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, nonetheless it is very striking that a mapping of thorps does not respect the supposed line of the Danelaw: there is no distinction between 'English' and 'Scandinavian' territory. This agricultural revolution, then, if that is what the thorp-names indicate, seems to have been a shared one, and indeed even the place-name element may have been shared between Old English and Old Norse. But the high frequency of Norse personal names as the first element in thorp-names remains significant: in keeping with the evidence of the Grimstons and the bys, the Danelaw thorps may well indicate a greater, or more accelerated, tendency towards the individual ownership of small estates.

All three of our main types of settlement names, then, seem to reveal a transformation in patterns of land-holding, in which land was passing out of royal, or aristocratic, or ecclesiastical control into private possession on a much smaller scale, and Norse personal names very frequently form the first element for all three types of names. All three types of names appear to have arisen at a relatively early date (that is, well before the Norman Conquest), and among a Scandinavian speech community. As to whether these places with Scandinavian names represent new settlements or not, the best interpretation at present is that, on the whole, the Grimstons are likely to be older, well-established Anglo-Saxon settlements and the thorps are likely to be new developments, while the bys sit somewhere in the middle and cover a variety of possibilities.

Grimstons, bys, and thorps have been the three categories of names which have received most attention from scholars, but they by no means add up to form the full corpus of Scandinavian, or Scandinavian-influenced, settlement names in England, and in Yorkshire: a considerable number of settlements bear Old Norse names outside of these three categories. Fellows-Jensen, in her corpus of Scandinavian settlement names recorded in Domesday Book, counted a further 30 settlements named after some sort of habitation, and 104 named after a topographical feature. The habitative category would include examples such as Lofthouse [WR] (< lofthús 'house with a loft'), Scorborough [ER] (< skógar-búð 'hut in a wood'), Upsall [NR] (< upsalir 'high dwellings'). The most common subtypes in the topographical category are settlements named after rivers and other features associated with water (for example, Ellerbeck [NR] (< elri-bekkr 'alders stream'), Nunburnholme [ER] (< brunnum 'at the streams', with Nun- a later addition), and the several settlements named Holme (< holmr 'higher ground among marshes, water-meadow') and Wath (< vað 'ford'); settlements named after hills and valleys (for example, Howe [NR] (< haugr 'mound, barrow, hill'), Sedbergh [WR] (< set-berg 'flat-topped hill'), and Thixendale [ER] ('Sigsteinn's valley'); and settlements named after woods and clearings (for example, Aiskew [NR] (< eiki-skógr 'oak wood'), Langthwaite [WR] (< lang-þveit 'long clearing'), and Rookwith [NR] (< hrókr-viðr 'rook wood'). In most of these cases the assumption must be that the topographical name arose from a feature of the landscape, and was extended or transferred to a nearby settlement. Whether the settlements bearing Norse topographical names were newly established, or were pre-existing English settlements that were re-named, must be decided on a case-bycase basis.

So far this discussion has only attended to settlement names given in the Old Norse language. But there are other types of place-names that, if anything, testify even more strongly to the quantity and distribution of Norse speakers in Viking Age England - and thus are vital evidence for migration and settlement. The first of these is the very great number of pre-existing Old English names that have been 'Scandinavianized' in some way by Old Norse speakers. This phenomenon of Scandinavianization was touched on above in the context of Scandinavian-style stone sculpture occurring in villages with English names, but it merits further discussion. Although Old English and Old Norse were closely related languages, there were important differences between them, not least in phonology: for example, Old English had the sound sh where Old Norse had sk, ch where Old Norse had k, d where Old Norse had ð, ā where Old Norse had ei, ēa where Old Norse had au, and so on. Many such differences were systematic and predictable, and so in effect were regular distinctions in pronunciation and accent, just like (for example) the long and short a in southern and northern Modern English bath or grass.

The consequence of this is that, in the mouths of Norse speakers, many English place-names underwent adaptation - either because the English name contained a sound not found in Norse, or because Norse speakers evidently perceived the correspondences between English pronunciation and their own. So, for example, the place-name Rawcliff Bank [NR] derives from Old English rēad-clif 'red cliff', and this English form is recorded in at least one source. But later forms show that the first element of the name was Scandinavianized to the cognate Old Norse rauðr, and the modern form of the name descends from this Scandinavianized variant. The place-name Rawcliff(e)/Roecliffe occurs four other times in Yorkshire: it is only in the case of Rawcliff Bank that we possess written evidence for both the English and Scandinavianized forms, but we can assume with certainty that the same process of Scandinavianization has occurred in every case. Countless other examples could be cited. For instance, in Brayton [WR], as we have already seen, Old English brād 'broad' has been replaced by cognate Old Norse breiðr in Stainborough [WR], Stān has been replaced by steinn; in Skirlaugh [ER], scīr 'bright' has been replaced by skírr, and so on.

In all of these examples the Scandinavianized form contains a comprehensible Old Norse word, because a Norse term existed that was cognate with the original English one (rauðr, breiðr, steinn, skírr); we are back in the territory of the 'Carlton hybrids'. But in many cases where no Norse cognate existed, the process of Scandinavianization still occurred - as it must have done inevitably, as what it represents is an incoming speech community adapting names into more congenial sound patterns, better able to be articulated. The result in these cases, however, would either not be a comprehensible Norse word, or (by chance) an unrelated Norse word of doubtful suitability: for example, Lothersdale [WR] shows the substitution of Norse ð for English d (in Old English loddere 'beggar'), East Keswick [WR] shows the substitution of Norse k for English ch (in Old English cēse 'cheese'), and East and West Scrafton [NR] shows the substitution of Norse sk for English sh (in scræf 'cave'). Skipton [WR] gives a good example of how the resultant name might be inappropriate rather than simply meaningless: substitution of Norse sk for English sh (and shortening of the vowel) has caused an original 'sheep settlement' (Old English scīp) to become 'ship settlement' (Old Norse skip). There is an abundance of Scandinavianized names in Yorkshire (as elsewhere in the Danelaw), and they serve as an unusually good window (or hearing loop) onto the Norse accents and speech habits to be heard in Viking Age England. We should therefore remind ourselves that, for such Scandinavianized variants to have entered into the written records of the region, they must have been widely used and widely accepted; there were, presumably, many more Scandinavianized forms that existed only as spoken variants and were never recorded in writing. Scandinavianized names supply a striking indication, then, of the strength and influence of the Old Norse speech community in Viking Age Yorkshire; for Old Norse speakers to have affected permanently the pronunciation of many English place-names, one assumes that they must have been numerous and (near-)ubiquitous.

Let us move on, finally, to the significance of place-names that are not settlement names at all, often grouped under the label of 'minor names': field-names, topographical names, and river-names. (Street names will be discussed in Chapter 6.) There has been a good deal of excellent research on the field-names of the Danelaw, though relatively little of this has been focused on Yorkshire. Field-names are important because they are likely to have arisen in a 'bottom-up' fashion, through the name-giving practices of the local agricultural population rather than through the 'top-down' administrative labelling of a small elite. Field-names are thus able to give us access to the language, or at least the vocabulary, of a particular locality, and if that language should be heavily Old Norse, or Norse-influenced, then it would seem to indicate the common use of Norse among the farmers and workers in that area. The snag is that field-names tend to be recorded late, usually not before the twelfth or thirteenth century at the earliest, at which point Old Norse will not have still been a living language in England; so we must use the field-names as a pointer to reconstruct the language of the area at whatever earlier point the lexicon of field-names came into existence. A corpus of Yorkshire field-names is readily available in A.H. Smith's English Place-Name Society volumes, though only for the West Riding did Smith organize this material geographically. For the heavily Scandinavianized North and East Ridings Smith notes that Norse elements are common in the field-names of the region, including (but not limited to):

- deill 'portion of land'

- engr 'meadow, pasture'

- flöt 'level ground'

- garðr 'enclosure'

- gata 'road'

- haugr 'mound, barrow, hill'

- höfuð 'head'

- holmr 'higher ground among marshes, water-meadow'

- kelda 'spring'

- leirr 'mud'

- lundr 'copse'

- marr 'pool'

- vrá 'corner, nook',

- and þveit 'clearing'

The heavy Norse influence on the field-naming vocabulary of the region is clear enough.

A study of the names of minor topographical features - hills, crags, woods, and so on - would reveal the same pervasiveness of Norse-derived vocabulary, at least in some parts of the county. Such Norse-derived minor names are innumerable, and can probably be appreciated better from large-scale Ordnance Survey maps than from the English Place-Name Society county volumes. Again, the point is not that these names must have been given by Norse speakers in the Viking Age - though some of them may well have been - but rather that they bear forceful witness to the Norse influence exerted on vocabulary and name-giving in Yorkshire, an influence that does in turn bear witness to the major population of Norse speakers that must have existed at one time. But one category that may possibly indicate early Scandinavian land-taking is an interesting group of names whose second element is dalr ('dale', perhaps sometimes replacing earlier Old English dæl, of identical meaning) and whose first element is a Norse personal name. Examples include Blakes Dale ('Bleikr's dale') and Thixendale ('Sigsteinn's dale') in the East Riding, Garsdale ('Garðr's dale') in the West Riding, and a whole raft of names in the North Riding: Apedale (Ápi), Aysdale (Ási), Bransdale (Brandr), Fangdale (Fangi), Gundale (Gunni), Raisdale (Røyðr), and Rosedale (Russi). These names possibly indicate Scandinavian lords assuming authority over a wider extent of land than simply a single, closely delimited settlement. Just occasionally we have a pairing of names at the same place between dale-names and other types: Commondale and Coldman Hargos [NR] were earlier Colemandale and Colemanergas ('shielings'), both preserving the Hiberno-Norse name Colman.

River-names form something of a special case of topographical names. The names of rivers and streams possess remarkable linguistic 'inertia', and historically have been very slow to change: for this reason many rivers in England, especially major ones, still bear Celtic names - or even pre-Celtic, non-Indo-European ones. So it is all the more notable that a considerable number of water-courses in Yorkshire bear Norse names, for example the Brennand, the Rawthey, and the Skell in the West Riding ('the burning one', 'the red river', and 'the resounding one'), and the Bain, the Greta, and the Seph in the North Riding ('the straight one', 'the rocky river', and 'the calm one'). In addition, there is a host of names whose second element is 'beck' (Old Norse bekkr) and whose first element is Norse too, for example Arkle Beck, Costa Beck, and Thordesay Beck, all in the North Riding ('Arnkell's beck', 'the choice river', and Þórdis' river'). For Norse river-names to be established, a necessary precondition would seem to be a widespread and substantial population of Norse speakers; like field-names, river-names do not fit easily into a model of name-giving which foregrounds elite agency.

With field-names, and topographical names such as river-names, we have, as noted, left settlement names behind, and such names are not in themselves onomastic evidence for settlement. But indirectly, as has been said, they are exceptionally important, as pointers to a substantial Norse-speaking population in early medieval Yorkshire. The place-name evidence is vast, and of enormous value for any study of Viking Age England. Here, it has been interrogated to see what it reveals of migration and settlement; in the next two chapters, we will investigate more what it can tell us about cultural and social history.