The Arthurian Legend

See also King Arthur and St Petroc's Church, Bodmin Index:

- Introduction

- The Legend

- The Link to Celtic Mythology

- Medieval Sources

- Clan Arthur

- References

- Links

- Royal Mail

- Rare & Collectable Books

Introduction

"Worlds of Arthur - Facts & Fictions of the Dark Ages" (2013) Professor Guy Halsall at pages vii, viii & 51 to 86

Preface

… I was reading the latest populist Arthurian history to hit the shelves. Positive reviews in war-gaming magazines suggested that it presented a plausible, scholarly case. It didn't, and this annoyed me. Almost every bookshop in the UK has at least half a shelf of this sort of book about 'King Arthur'. Written by amateur enthusiasts, each reveals a different 'truth' about the lost king of the Britons. All are mutually incompatible but usually based in whole or part upon the same evidence. Each author fanatically believes his version (and the author is usually a he) to be the true story, hushed up by horrid academics or by political conspiracies (usually by the English) or sometimes his rivals. Obviously they can't all be right. In fact none of them is, because, as this book will make clear, none of them can be. Arthur, if he existed - and he might have done - is irretrievably lost.

Such books sell, no doubt. Interest in 'King Arthur' is enormous. Yet they sell not because the 'interested layman' necessarily has a vested interest in the argument that King Arthur was Scottish, Cornish, Welsh, or from Warwickshire or even, I suspect, in whether or not he existed. They sell because people believe the misleading claims of these books' covers, to reveal the 'truth' or unlock the 'secret'. In other words, they want to know. I could decry the cynicism of publishers who profit from this audience's sincere but ill-informed desire for knowledge and from these authors' dishonesty but I am more troubled by the inactivity of my own, historical profession. Why has it done nothing to help this interested lay audience, by propagating the results of the specialist work that disproves any and all claims to have discovered the real Arthur? Why has it not at least made available some insight into how to judge, and see through, the siren claims of the pseudo-histories, as I will refer to non-academic treatments of this period that ignore recent scholarly analyses?

This book responds to this demand. Before going any further, I should confess to being what might be termed a romantic Arthurian agnostic. That is to say that I wish that Arthur had existed but that I must admit that there is no evidence - at any rate none admissible in any serious 'court of history' - that he ever did so. Simultaneously, though, I also concede that it is impossible to prove for sure that he didn't exist, that one cannot demonstrate for sure that there is no 'fire' behind the 'smoke' of later myth and legend. If that sounds too wishy-washy, I will argue that this is the only attitude that can seriously be held concerning the historicity of the 'once and future king'.

4. The antimatter of Arthur

Reassessing the Written Sources

… This chapter examines the literary evidence again, source by source, in more or less chronological order.

Two extremely important points must be set out at the start. The first is that medieval writers and their audiences … expected different things from 'history'. Unlike 'moderns', medieval people did not have a category of 'factual history' separate from what might today be thought of as 'historical fiction', 'alternative history', or even 'fantasy'. A moral 'truth', a good story with a valuable lesson, was far more important than factual accuracy …

… Closely related to this is the second point: sources must be taken as a whole. You cannot cherry-pick some bits and ignore others according to what you want to believe. You cannot winnow out fact from fiction solely on the basis of modern ideas …

Gildas

The basic building block for the traditional political historical narrative of fifth- and sixth-century Britain is Gildas' De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain). This was certainly composed in Britain during our period but that is about all that can be said with absolute confidence about its date and provenance. We know nothing about Gildas himself … It is impossible to know where Gildas wrote except that it was probably not in a part of Britain controlled, in his day, by 'Saxons'. Nor can we say when he was writing. It is frequently claimed that he wrote circa 540 but this date lacks any solid foundation …

… There is some evidence for an 'early Gildas', writing in the late fifth century. This includes Gildas' rhetorical education, his Latin style, his theological concerns, and a rereading of his historical section and where he places himself within it. I tend towards this interpretation, although it cannot be proven. It is unlikely that Gildas wrote before 480/490 or much after about 550; beyond that we cannot go …

… The most significant discussion for present purposes concerns that oft-cited chronological indicator, Gildas' phrase about Mount Badon …

… Of course we still don't know when Gildas' birth or the siege of Badon Hill were … If pressed, I might plump for the first decade of the century …

… Gildas' failure to mention Arthur has produced all sorts of speculation. Later medieval writers invented stories about how Gildas and Arthur fell out but they were, like us, trying to account for - to them - an inexplicable omission … Finally, either 'Arthur' is another name for one of Gildas' characters - Ambrosius Aurelianus, 'the proud tyrant', or the Cuneglasus mentioned in the 'complaint to the kings' and addressed as 'bear' (the arth- element of Arthur's name means 'bear') - or Arthur belongs chronologically after Gildas. The second option might be possible, especially if Gildas is moved back to the very late fifth century. It is, however, obviously a pretty weak, if convenient, argument to explain a silence which, if Arthur never existed, would need no explanation. None of the suggestions for characters who are 'really' Arthur finds any evidential support. Like the first proposal, they spring from a desire to make the data fit an a priori assumption and thus account for the absence of actual evidence.

Editor's note: The Battle of Badon was a battle thought to have occurred between Celtic Britons and Anglo-Saxons in the late 5th or early 6th century. It was credited as a major victory for the Britons, stopping the encroachment of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms for a period. It is chiefly known today for the supposed involvement of King Arthur, a tradition that first clearly appeared in the 9th-century Historia Brittonum. Because of the limited number of sources, there is no certainty about the date, location, or details of the fighting.

The earliest mention of the Battle of Badon is Gildas' De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae ("On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain"), written in the early to mid-6th century. In it, the Anglo-Saxons are said to have "dipped [their] red and savage tongue in the western ocean" before Ambrosius Aurelianus organized a British resistance with the survivors of the initial Saxon onslaught. Gildas describes the period that followed Ambrosius' initial success:

"From that time, the citizens were sometimes victorious, sometimes the enemy, in order that the Lord, according to His wont, might try in this nation the Israel of to-day, whether it loves Him or not. This continued up to the year of the siege of Badon Hill (obsessionis Badonici montis), and of almost the last great slaughter inflicted upon the rascally crew. And this commences, a fact I know, as the forty-fourth year, with one month now elapsed; it is also the year of my birth."

The battle is next mentioned in an 8th-century text of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. It describes the "siege of Mount Badon, when they made no small slaughter of those invaders" as occurring 44 years after the first Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. Since Bede places that arrival during or just after the joint reign of Marcian and Valentinian III in 449 - 456, he must have considered Badon to have taken place between 493 and 500. Bede then puts off discussion of the battle - "But more of this hereafter" - only to seemingly never return to it. Bede does later include an extended account of Saint Germanus of Auxerre's victory over the Saxons and Picts in a mountain valley, which he credits with curbing the threat of invasion for a generation. However, as the victory is described as having been accomplished bloodlessly, it was presumably a different occasion from Badon. Accepted at face value, St. Germanus' involvement would also place the battle around 430, although Bede's chronology shows no knowledge of this.

The earliest surviving text mentioning Arthur at the battle is the early 9th-century Historia Brittonum, in which the soldier Arthur is identified as the leader of the victorious British force at Badon:

"The twelfth battle was on Mount Badon in which there fell in one day 960 men from one charge by Arthur; and no one struck them down except Arthur himself."

The Battle of Badon is next mentioned in the Annales Cambriae ("Annals of Wales"), assumed to have been written during the mid- to late- 10th century. The entry states:

"The Battle of Badon, in which Arthur carried the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and three nights upon his shoulders [or shield] and the Britons were the victors"."

That Arthur had gone unmentioned in the source closest to his own time, Gildas, was noticed at least as early as the 12th century hagiography that claims that Gildas had praised Arthur extensively but then excised him completely after Arthur killed the saint's brother, Hueil mab Caw. Modern writers have suggested the details of the battle were so well known that Gildas could have expected his audience to be familiar with them.

Geoffrey of Monmouth's circa 1136 Historia Regum Britanniae was massively popular and survives in many copies from soon after its composition. Going into (and fabricating) much greater detail, Geoffrey closely identifies Badon with Bath, including having Merlin foretell that Badon's baths would lose their hot water and turn poisonous. He employs aspects of other accounts, mixing them:

- the battle begins as a Saxon siege and then becomes a normal engagement once Arthur's men arrive

- Arthur bears the image of the Virgin both on his shield and shoulder

- Arthur charges, but kills a mere 470, ten more than the number of Britons ambushed by Hengist near Salisbury

Elements of the Welsh legends are also added: in addition to the shield Pridwen, Arthur gains his sword Caliburnus and his spear, Ron. Geoffrey also makes the defence of the city from the Saxon sneak attack a holy cause, having Dubricius offer absolution of all sins for those who fall in battle.

Bede

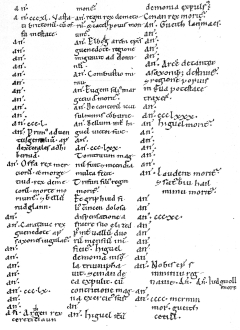

After Gildas, no insular source describes the 'world of Arthur' until we come to the famous 'Venerable Bede' in early eighth-century Northumbria (in the monastery of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow to be exact). Bede was a chronographer before he was a historian; he was interested in the measurement of time, essentially for theological purposes: calculating the proper date of Easter; establishing the age of the world, and so on. This led him to popularize the AD system of dating still in use … he didn't invent it but he might as well have done. In turn it brought about his two chronicles (the lesser and the greater: Chronica Minora and Chronica Majora): lists of years and the events that happened in them. At the end of his life his interest in chronology and belief that the contemporary English Church had degenerated from a putative seventh-century golden age led him to compose his most famous work, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which he completed in 731, shortly before his death (735). We therefore know immensely more about Bede, his life, and circumstances than we do about Gildas.

Bede put his version of British history between the end of Roman rule and St Augustine's arrival in the latter part of Book I of the Ecclesiastical History … It is a fascinating attempt to put together a coherent narrative from diverse components, almost all of which still survive. In other words, Bede apparently knew as little as we do about the period between circa 410 and circa 597. His principal source is Gildas' On the Ruin, which he read as a single narrative of events, probably … a mistake but one which almost everyone who has read Gildas since has made. Into this he wove information from several other sources … The status and origins of the information Bede added to Gildas' story are essentially unknowable …

… We need to emphasize that Bede's is a significant mutation of Gildas' story …

… This neatly underlines how Bede knew almost nothing about the 200 or so years before Augustine's arrival independently of sources we still have. Thus his account has flimsy and unreliable foundations, and can bear little weight. For Bede that was irrelevant. The point of the Ecclesiastical History was that the Britons had lost control of Britain's green and pleasant land, driven out by the Saxons, chosen by God to be His scourge of a sinful people. Bede felt that the Anglo-Saxons could go the same way if they didn't mend their ways …

… Note, though, that neither Bede, nor any of his sources, oral, legendary, or written, says anything about 'Arthur'. For this the most straightforward and, given that we still have almost all of Bede's sources, unsurprising explanation is simply that he (and they) didn't know anything about him. It doesn't necessarily imply that Arthur never existed; a perfectly acceptable and consistent qualification of the explanation just given is 'or, if they had heard of him, he didn't matter to their story'.

The History of the Britons

So we come to the first datable source to mention Arthur, the History of the Britons ('HB'), written in 828/9, in North Wales. The name Nennius (or Nemnius) was only attached to a later manuscript of this source …

The HB shows just how elaborate legends about the fifth century had become by the early eighth. Structurally the work looks like a mess … Then we come to the 'Battle List of Arthur' … which serves as a linking passage introducing the History's account of northern Britain, mainly in the seventh century … A list of the 'Wonders of Britain', including the second passage about Arthur (mentioned in Chapter 1), is appended to the end of the History …

… The HB assembles material from a string of sources, some of which can be identified but almost none of which has any claim to reliability … Much of the story is woven from Bede's and thus, behind that, Gildas' accounts …

… And so we return to Arthur's battles … it is often supposed to represent a fragment of a lost poem celebrating Arthur's achievements. The battles themselves have engendered any number of pseudo-histories, purporting to reconstruct King Arthur's campaigns. Their locations are suggested and a putative military context invented, within the traditionally supposed overall situation of a war between defending Britons and invading Anglo-Saxons … Of course the locations are usually chosen with the context in mind, so it is almost invariably a circular argument. On the other hand, sceptics counter by saying that, whether this is a poem or not, we have no way of knowing whether it gives any sort of historical account. By 830 there had been at least 300 years for poems to be composed and elaborated, for characters to be invented, battles made up, for real battles from various contexts to be brought together and ascribed to a mighty, legendary war leader.

… As we have seen, it seems unlikely that Gildas does say that Badon was won by Ambrosius Aurelianus. The other five locations are found nowhere else in surviving literature, making it at least 'not proven' that they are a diverse medley of famous battles assembled and connected with Arthur.

One other point must be stressed. With the exception of the 'Battle of the Caledonian Forest', which ought to be somewhere north of Hadrian's Wall, and Linnuis, which might be Lindsey (Lincolnshire), the locations of all of these battles are unknown and unknowable. This is of supreme importance if reading modern pseudo-histories so I'll say it again:

THE LOCATIONS OF ALL OF THESE BATTLES ARE UNKNOWN AND UNKNOWABLE The Historia Brittonum is a fascinating, infuriating source. It still holds many secrets, doubtless including ones that no one will ever uncover. Most of them, however, relate to politics and history-writing in early ninth-century Wales. That topic is no less important or interesting than fifth-century history. Let's be clear about that. As with Gildas and Bede, we must identify the questions which the source does address rather than hammering it to fit those which it doesn't.

… By the same token, though, everything that the HB does tell us about Ambrosius is surely fictitious. On this analogy, the dubious nature of the HB as a source for Arthur does not mean that no such person ever lived during the fifth or sixth centuries. In the end, the Historia Brittonum provides no decisive grounds for accepting or rejecting 'the historical Arthur'; 'you pays your money and takes your choice'. However, it cannot be stressed too strongly that the HB does not provide any reliable information about any historical figure of that name.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Our final major source, much used in Arthurian pseudo-histories, is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, first composed at or near King Alfred's court in the 880s and continued in various different manuscripts down to the reign of King Stephen (1135-54). The Chronicle's account of the fifth century is extremely dubious and it is staggering that people took it literally for so long …

The Chronicle's sources were Bede, whom we've already discussed and dismissed as a reliable independent witness for the fifth century, and a range of genealogical and other legendary sources …

There could be snippets of sixth-century fact in the Chronicle but it is impossible now to disentangle them from the narrative and structure of its authors' propaganda, or from the huge dose of myth, legend, and pun with which they injected it.

The Welsh Annals

The last insular narrative to consider is the Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals) … this contains two 'Arthurian' entries, one concerning Badon, the other Arthur's death at Camlann. The source itself probably belongs to the later tenth century; its last entry is 954 and the last year counted 977. The earliest manuscript dates to around 1100 (the Annals are appended to a text of the HB), though, and the two other variants belong to the thirteenth century. Immediately, therefore, we note how much later it is than Arthur's alleged existence … There is no persuasive reason to presume that the Welsh Annals simply transmit earlier more contemporary records in unmodified form. A closer look confirms these suspicions.

The second obvious point to remark upon is the similarity between its account of Badon and the HB's description of Castell Guinnion … there is no prima facie reason to take the account very seriously. Like the HB's story it is clearly legendary …

The Camlann entry must come from somewhere else, however. This is the first mention of Arthur's last, climactic battle and of Medraut …

… The Welsh Annals remain a dubious source for 'the historical Arthur'. Their author possibly had access to some Arthurian tradition otherwise lost, different from the account handed down from Gildas via Bede and the HB (an argument, in other words, for the 'bubbling kettle' reading) … but it is impossible to argue that these traditions had any better claim to historical reliability.

Welsh 'heroic' Poetry

The other source possibly from before AD 1000 to mention Arthur is the poem Y Gododdin … some suppose Y Gododdin's stanza about Gorddur to be the earliest mention of Arthur. The poem, however, is not clearly datable. The events it describes are generally supposed to relate to the period around 600. Some historians have suggested a half century earlier but on no good grounds …

So where does this leave Gorrdur, who 'was not Arthur' ? It is certainly odd that 'pro-Arthurians' argue that the decisive evidence for Arthur's historical existence is a source saying that someone wasn't Arthur. Stating that someone was or was not 'Arthur' implies nothing about Arthur's existence …

We cannot rule out Arthur's existence on the basis of these doubts, but it is equally impossible to use this stanza from Y Gododdin as evidence that he did exist. All we can say is that, by whatever date this stanza was composed, the poet knew of an Arthur figure who could be used as a benchmark for military prowess. Whether that Arthur was a really existing leader or a mythic figure cannot be deduced.

The issuers just discussed apply to the rest of Welsh 'heroic' verse, including the works of 'Taliesin' about other legendary northern British military heroes like Urien and Owain of Rheged, which - highly significantly - does not otherwise mention Arthur.

Odds and Ends

The foregoing list encompasses pretty much all of the written material deemed to be of relevance to reconstructing the 'World of King Arthur'. A little more needs to be said about one or two additional sources.

The Life of St Germanus

… The Life was composed about thirty years after Germanus' death but its author knew people who had known the saint, including Bishop Lupus of Troyes who accompanied Germanus to Britain. That said, it is a work of hagiography (writing about saints), filled with miracles. Telling a sober history as a repository of facts for later scholars was no part of its purpose. It has been argued - at one extreme - that the entire Life is a patchwork of hagiographical commonplaces intended as a teaching instrument about proper theological beliefs and the correct role of a bishop. One cannot simply take the Life, ignore the miraculous elements, and sift out the rest as 'proper' history; one must take it as a whole …

The Gallic Chronicle of 452

The other contemporary mainland European source for British events is the Gallic Chronicle of 452. This anonymous work was apparently composed somewhere in south-east Gaul (Valence or Marseilles have been suggested). It can hardly be called detailed and, like most fifth-century sources, its principal interest is doctrinal controversy. It is a series of fairly terse annalistic entries that stops in 452, hence the name: the whole text seems to have been written at about that date. Amongst these are two British entries. The first mentions that the British provinces were 'laid waste by Saxon invasion'. The second says that the British provinces were 'subjected to the authority of the Saxons' …

… quite what the chronicler (in south-eastern Gaul) or his informants meant when they said that Britain had been subjected to Saxon authority is unknown. We cannot determine whether this and the other Saxon attack were the only British events the chronicler knew of, or whether they were selected for rhetorical or stylistic effect from a more general 'background noise' of tales of Saxon attacks. This makes it impossible to evaluate these events' significance. The evidence of the Gallic Chronicle of 452 cannot bear much weight.

Welsh Sources

Most of the relevant Welsh sources have been discussed already. There are other traditions and legends, which appear in later medieval Welsh and Breton saints' lives and in more Welsh poetry … It does not require detailed analysis. Suffice it to say that these sources are all very late and postdate the florescence of Arthurian legend … The extent of influence from the other Arthurian traditions flourishing by then cannot be assessed. Nor can we identify what might be separate traditions or evaluate the extent to which they might preserve earlier tales. Thus these stories cannot reliably be projected back into the fifth and sixth centuries.

Names

Finally, we have encountered three genuinely historical Arthurs living in the late sixth century, which some have seen as arguing that a real Arthur existed not long before. This is quite an attractive suggestion although it is, of course, not the only factor that could produce three minor royals sharing an unusual name at about the same time. To other writers, one of them actually is our 'King Arthur', the son of Aedan being the most popular candidate. After all, the earliest possible (or, alternatively, most optimistic) date for the stanza referring to Arthur in Y Gododdin would be within a generation of the lives of these three. Sadly we know little or nothing about them. None of them appears to have been particularly noteworthy. This has usually been the basis of attempts to dismiss the idea that one or other of them might be 'King Arthur', the mighty warrior of lore. This is a weak argument, given the scarcity of references to Arthur in the 400 years after their deaths and the failure (evident from the Armes Prydein's silence) of the Historia Brittonum to make a heroic national figure out of its Arthur, at least until Geoffrey of Monmouth took up the cause 300 years later. The fact that even John Morris had to acknowledge that no one else was known to have called their son Arthur for another 500 years or so, until the mid-eleventh century - in other words until about the time of the explosion of Arthurian legend - is further, weighty evidence against any historical Arthur being at all well known, even in legend, in the second half of the first millennium. That the next, eleventh-century, Arthurs we know about are all Normans or Bretons, rather than Welshmen or Scots, supports the notion … that the Arthur legend was largely reintroduced into Great Britain at the Norman Conquest. The possibility that one of the late sixth-century Arthurs might, for whatever reason now lost to us, be the reality behind the Arthur legend might very well be the simplest and most prosaic - but also (if I'm honest) slightly disappointing - solution to the whole Arthurian conundrum.

Place-names

Britain abounds with 'Arthur' place-names, from Scotland to Cornwall. Most of these lie in the highland areas of the island but there is little or no use that the historian can make of this fact. These names are not recorded until well after the explosion of the Arthurian legend in the eleventh century. That the legendary corpus frequently associated Arthur with the highlands, perhaps through his leadership of the Britons, is reason enough for the popularity of Arthur names in those areas. What is more, landscape features very often have personal names attached to them without there being any historical basis to the association … South Cadbury's 'Camelot' associations may well have grown considerably after John Leland's visit in the sixteenth century. [4]

Conclusion

If you want to believe in a real 'King Arthur', the analysis of the written sources for fifth- and sixth-century Britain makes depressing reading. With the exception of Gildas (and restricting Gildas' testimony mainly to its 'non-historical' elements) and probably the Life of Germanus' account of the bishop's first visit, there is no reliable written source for this period. Unless some important new written sources are discovered, which is unlikely, the construction of a detailed narrative political historical account is quite out of the question and always will be. The claim of any book that purports to present such a history should be rejected immediately and out of hand. Such attempts represent fiction, no more and no less. Some of the 'old chestnuts' by which modern pseudo-histories try to circumvent this unpalatable but ineluctable conclusion are dealt with in Chapter 7. The sources are interesting and useful if pressed into service in the exploration of other questions - questions they can answer - such as about the idea of history in ninth-century England and Wales. For British political history between 410 and 597 they are quite useless. Shadows of real events and people might survive in the material compiled between the early eighth and the late tenth century but we cannot now identify them. However, if our written evidence is absolutely incapable of proving that Arthur existed, and certainly of telling us anything reliable about him, its faults do not prove that he did not exist. Now, having more or less swept away all the written sources once thought useful for the history of fifth- and sixth-century Britain, we must return to the archaeological evidence and examine whether it makes up for this documentary shortfall.

Professor Guy Halsall has taught at the universities of London and York, where he has been a professor of history since 2006. His early specialism was in the history and archaeology of the Merovingian period (circa 450 - 750), and he has since published widely on a broad range of subjects, including death and burial, age and gender, violence and warfare, barbarian migrations, and humour. This investigation into the 'worlds of Arthur' brings him back to the study of early medieval British history and archaeology with which his scholarly training began.

[4] Editor's note: the first known author to refer to Cadbury as Camelot is John Leland in 1542. John Leland (1503 to 1552) was a staunch patriot, and believed firmly in the historical veracity of King Arthur. He therefore took offence when the Italian scholar Polydore Vergil cast doubts on certain elements in the Arthurian legend in his Anglica Historia (published in 1534). Leland's first response was an unpublished tract, written perhaps in 1536, the Codrus sive Laus et Defensio Gallofridi Arturii contra Polydorum Vergilium. He followed this with a longer published work, the Assertio inclytissimi Arturii regis Britannia (1544). In both texts, Leland drew on a wide range of literary, etymological, archaeological and oral sources to defend the historicity of Arthur. Although his central belief was flawed, his work preserved much evidence for the Arthurian tradition that might otherwise have been lost.

Leland's material provides invaluable evidence for reconstructing the lost "tomb" of Arthur (a twelfth-century fabrication) at Glastonbury Abbey. On his itinerary of 1542, Leland was the first to record the tradition (possibly influenced by the proximity of the villages of Queen Camel and West Camel) identifying the hill fort of Cadbury Castle in Somerset as Arthur's Camelot:

"At the very south ende of the chirch of South-Cadbyri standeth Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle, apon a very torre or hille, wunderfully enstregnthenid of nature … The people can telle nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resortid to Camalat."

"The Secret Library" (2016) Oliver Tearle at pages 41 to 44

Chapter 2

The Middle Ages

Merlin's Debut

The stories of King Arthur draw upon a similar historical time period to Beowulf. Indeed, both names, Arthur and Beowulf, are thought by some linguists to have etymological connections with bears, conveying their fearsome might and dauntless courage (though in both cases the theory has been disputed). The chief difference is that Arthur fought against the Angles and Saxons, the very people who brought the tale of Beowulf with them to Britain. Arthur is a pre-Saxon figure, king of the 'Britons' or natives, defending his land against the Germanic hordes.

Arthur's story has been told countless times by writers down the ages, since at least the ninth century. As a result, there are some strange and inconsistent ideas surrounding the legend. Most people know of the tale of the 'sword in the stone' - memorably told, or rather retold, by T. H. White in his 1938 novel The Sword in the Stone, later filmed by Disney - which features Arthur plucking Excalibur from a stone, an act that could only be performed by the true king. (This myth may have its basis in the very real practice of casting metal swords in stone moulds, from which they would have to be extracted once the metal had set.) But in most renderings of the tale, the sword Arthur pulls from the stone is not Excalibur: Excalibur is the sword he receives later, once he has been crowned king, from the Lady of the Lake. In some versions of the story, it is Galahad who has to pull the sword from the stone. In others, Bedivere, not Arthur, receives the sword from the Lady of the Lake. In the earliest romances, it is Arthur's nephew Gawain who owns a sword named Excalibur. These inconsistencies are a result of the fact that many authors, not one, have contributed to the Arthurian story, so there is no definitive version of the legend. Instead, our idea of Arthuriana is an amalgamation and conflation of various myths, stories and rewritings.

However, if there was one writer who helped to bring Arthur to an international audience, it was the twelfth-century Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, whose Historia Regum Britanniae or History of the Kings of Britain was the most influential text for later writers of the Arthur myth. Geoffrey's History was a medieval bestseller in a world before printed books. As we've seen, Beowulf survived in one single scorched manuscript; there are over 200 copies of Geoffrey's History from the medieval period. When Geoffrey was writing, the line between history and fiction was by no means easy to draw, and as a result we cannot say how much of his History is grounded in fact and how much was later invention, whether his own or other people's.

The nineteenth-century French scholar Gaston Paris suggested that Geoffrey changed the Welsh Myrddin to Merlin to avoid resemblance to the Latin merda, 'faeces'.Geoffrey's account of the legendary king contains the first appearance of many of the iconic features of the Arthurian myth, including the wizard Merlin. (It also features some strange notions, such as the theory that Merlin was responsible for the construction of Stonehenge, having taken the huge stones from Ireland by magic. People remained confused about Stonehenge for some time after this: the seventeenth-century architect Inigo Jones thought it was a Roman monument.) As if all this wasn't enough of a cultural legacy, Geoffrey's History is also ultimately the source (albeit indirectly) for two of Shakespeare's plays, King Lear and Cymbeline.

Geoffrey of Monmouth had his own agenda in popularizing the Arthur myth, though quite what that agenda was continues to divide critics. He could well have been suggesting that the arrival of the Normans at the Battle of Hastings had put an end to the squabbles between the Saxons and the native Britons such as Arthur, but if this is the case, it's somewhat ironic that Geoffrey himself was writing against the backdrop of a bloody civil war raging between the Norman king Stephen and his cousin, Empress Matilda. What is certain is that subsequent authors have also reworked the Arthurian tale to reflect their own times. Francis of Assisi remarked that Arthur, along with other medieval pin-ups such as Charlemagne and Roland, were Christian martyrs who had been prepared to die in battle to defend their faith in Christ. There were numerous retellings of the Arthur legend throughout the Middle Ages, such as that by the Norman author Wace (pronounced 'wassy'), who added the Round Table, the French writer Chrétien de Troyes' poems of the late twelfth century (which added the character of Lancelot and the adulterous affair with Guinevere, wife of Arthur), the Alliterative Morte Arthure written in Middle English and dating from around 1400, and - most enduringly of all - Sir Thomas Malory's fifteenth-century prose work Le Morte d'Arthur.

"Merlin tale fragments discovered in Bristol archives" (30 January 2019) Steven Morris, The Guardian

An intriguing, previously unknown 13th-century version of a tale featuring Merlin and King Arthur has been discovered in the archives of Bristol central library.

The seven handwritten fragments of parchment were unearthed bound inside an unrelated volume of the work of a 15th-century French scholar.

Written in Old French, they tell the story of the Battle of Trèbes, in which Merlin inspires Arthur's forces with a stirring speech and leads a charge using Sir Kay's special dragon standard, which breathes real fire.

The fragments are believed to be a version of the Estoire de Merlin - the story of Merlin - from the Old French sequence of texts known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Lancelot-Grail Cycle.

Other versions of the cycle are known but this one features subtly different details. For example, different characters are responsible for leading the four divisions of Arthur's forces.

In addition, in other versions, Arthur and Merlin's enemy, King Claudas, is wounded on the thigh, while in the newly discovered fragments the nature of the injury is not specified. This may lead to a new interpretation of the text as upper-leg injuries are often used as metaphors for impotence or castration.

Dr Leah Tether, the president of the British branch of the International Arthurian Society and an academic based at Bristol University, cautioned that much more work needed to be done but said it was possible that these pages could be part of the version of the Vulgate Cycle that Sir Thomas Malory used as a source for his work Le Morte D’Arthur - which is the inspiration for many modern retellings of the Arthurian legend.

Scholars are not convinced that Malory used any of the versions that until now had been known about.

Tether said: "These fragments are a wonderfully exciting find, which may have implications for the study not just of this text but also of other related and later texts that have shaped our modern understanding of the Arthurian legend. There is a small chance that this could be connected to a version that Malory had access to but we are a long way from proving that."

If the fragments were printed in a modern paperback they would fill about 20 pages. There has been some damage to them, which means it will take time to decipher all the text.

"Time and research will reveal what further secrets about the legends of Arthur, Merlin and the Holy Grail these fragments might hold," Tether said.

"The south-west of England and Wales are, of course, closely bound up with the many locations made famous by the Arthurian legend, so it is all the more special to find an early fragment of the legend - one pre-dating any version written in English - here in Bristol."

"Fragments of medieval Merlin manuscript found in Bristol library reveal 'chaster' story" (6 September 2021) Alison Flood, The Guardian

Parchment fragments discovered in bindings of much later volumes reveal 'subtle but significant' variations on Arthurian legend.

The seven parchment fragments were found by chance in 2019 pasted into the bindings of four volumes from between 1494 and 1502 that are held in Bristol central library’s rare books collection. Academics have now established how they came to Bristol, how they differ from other versions of the story, and, using multispectral imaging, even what type of ink was used to write them.

Containing a passage from the Old French sequence of texts known as the Vulgate Cycle or Lancelot-Grail Cycle, which was written circa 1220-1225, the fragments themselves have been dated to 1250-1275 through palaeographic handwriting analysis, and located to northern, possibly north-eastern, France.

Digital processing enabled Bristol's Professor Leah Tether, medieval historian and manuscript specialist Dr Benjamin Pohl and medievalist Dr Laura Chuhan Campbell to read some parts of the text more clearly, and they discovered differences to other versions of the Merlin legend - for example, the Bristol fragments show a 'slightly toned-down' account of Merlin's sexual encounter with the enchantress Viviane, also known as the Lady of the Lake.

"In most manuscripts of the better known [version], Viviane casts a spell whereby three names are written on her groin that prevent Merlin from sleeping with her. In several manuscripts of the lesser-known version, these names are written on a ring instead," said Tether. "In our fragments, this is taken one step further: the names are written on a ring, but they also prevent anyone speaking to her. So the Bristol Merlin gets rid of unchaste connotations by removing reference to both Viviane's groin and the idea of Merlin sleeping with her."

"And the girl [Viviane] made Merlin lie down in her lap, and she started to ask him questions. She moved around him, and seduced him again and again until he was sick with love for her," runs the passage. "And then she asked him to teach her how to put a man to sleep. And he knew very well what she was planning, but nevertheless, he could not prevent himself from teaching her this skill, and many others as well, because Our Lord God wanted it this way. And he taught her three names, which she inscribed on a ring every time that she had to speak to him. These words were so powerful that when they were imprinted on her, they prevented anyone from speaking to her. She put all of this down in writing, and from then on, she manipulated Merlin every time that he came to talk to her, so that he had no power over her. And that is why the proverbs say that women have one more trick than the devil."

Looking at the bindings of the books, the academics worked out that the manuscript from which they had come had been designated as waste in either Oxford or Cambridge, and recycled as binding materials, probably before 1520. They believe the manuscript could have been seen as disposable because English versions of the Arthurian legend, such as Malory's Le Morte D’Arthur, had become available.

"We were also able to place the manuscript in England as early as 1300-1350 thanks to an annotation in a margin - again, we were able to date the handwriting, and identify it as an English hand," said Tether. "Most manuscripts of the text known to have been in England in the middle ages were composed after 1275, so this is an especially early example, both of Suite Vulgate manuscripts in general anywhere, but especially of ones known to have found their way to England from France in the middle ages."

The volumes are likely to have ended up in Bristol's collection, the academics believe, through Tobias Matthew, who collected many books while he was dean and bishop of Durham at the turn of the 17th century, later donating many to Bristol public library, which he co-founded in 1613.

The passages in the fragments begin with Arthur, Merlin, Gawain and other knights preparing for battle at Trèbes against King Claudas, ending with Merlin's stay with Viviane for a week, and his return to Arthur. Other variations include the names of the characters who lead the four divisions of Arthur's forces, and the location of a wound given to King Claudas, Arthur and Merlin's enemy. He is wounded through the thighs in other versions, but the fragment does not specify the nature of the wound; the academics said this "may lead to different interpretations of the text owing to thigh wounds often being used as metaphors for impotence or castration".

Digital processing also helped the academics discover what type of ink the scribes used. "[It] helped us to establish, since the text appeared dark under infra-red light, that the two scribes had in fact used a carbon-based ink - made from soot and called 'lampblack' - rather than the more common 'iron-gall ink', made from gallnuts, which would appear light under infra-red illumination. The reason for the scribes' ink choice may have to do with what particular ink-making materials were available near their workshop," said Tether.

The findings have now been brought together in The Bristol Merlin: Revealing the Secrets of a Medieval Fragment. "Besides the exciting conclusions, one thing that … the Bristol Merlin has revealed is the immeasurable value of interdisciplinary and trans-institutional collaboration, which in our case has forged a holistic, comprehensive model for studying medieval manuscript fragments that we hope will inform and encourage future work in the field," said Tether. "It has also shown us the very great potential of local manuscript and rare book collections in Bristol, particularly in the central library where there are many more unidentified manuscript fragments awaiting discovery."

The Legend

Although there are innumerable variations of the Arthurian legend, the basic story has remained the same. Arthur was the illegitimate son of Uther Pendragon, king of Britain, and Igraine, the wife of Gorlois of Cornwall. After the death of Uther, Arthur, who had been reared in secrecy, won acknowledgment as king of Britain by successfully withdrawing a sword from a stone. Merlin, the court magician, then revealed the new king's parentage.

Arthur, reigning in his court at Camelot, proved to be a noble king and a mighty warrior. He was the possessor of the miraculous sword Excalibur, given to him by the mysterious Lady of the Lake. At Arthur's death Sir Bedivere threw Excalibur into the lake; a hand rose from the water, caught the sword, and disappeared. Another sword, sometimes mistakenly identified with Excalibur, was drawn from a stone by Arthur to prove his royalty.

Of Arthur's several enemies, the most treacherous were his sister Morgan le Fay and his nephew Mordred. Morgan le Fay was usually represented as an evil sorceress, scheming to win Arthur's throne for herself and her lover. Mordred (or Modred) was variously Arthur's nephew or his son by his sister Morgause. He seized Arthur's throne during the king's absence. Later he was slain in battle by Arthur, but not before he had fatally wounded the king. Arthur was borne away to the isle of Avalon, where it was expected that he would be healed of his wounds and that he would someday return to his people.

Two of the most invincible knights in Arthur's realm were Sir Tristram and Sir Launcelot of the Lake. Both of them, however, were involved in illicit and tragic love unions - Tristram with Isolde, the queen of Tristram's uncle, King Mark; Sir Launcelot with Guinevere, the queen of his sovereign, King Arthur. Other knights of importance include the naive Sir Pelleas, who fell helplessly in love with the heartless Ettarre (or Ettard) and Sir Gawain, Arthur's nephew, who appeared variously as the ideal of knightly courtesy and as the bitter enemy of Launcelot.

Also significant are Sir Balin and Sir Balan, two devoted brothers who unwittingly slew one another; Sir Galahad, Launcelot's son, who was the hero of the quest for the Holy Grail; Sir Kay, Arthur's villainous foster brother; Sir Percivale (or Parsifal); Sir Gareth; Sir Geraint; Sir Bedivere; and other knights of the Round Table.

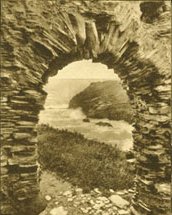

King Arthur's Castle, Tintagel, Cornwall

Tinted view of castle ruins

(Francis Frith postcard - 1904)Tintagel, Cornwall

Tinted view of the Valley

(Francis Frith postcard - 1895)King Arthur's Castle Doorway, Tintagel, Cornwall

(Francis Frith postcard - 1908)

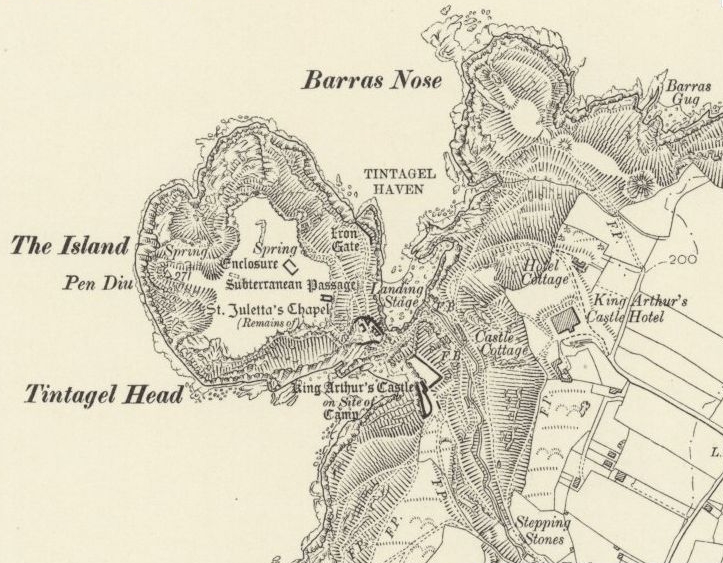

Ordnance Survey 1907: King Arthur's Castle (Tintagel)

"Has the real birthplace of King Arthur been found ?"

Daily Mail, 3rd August 2016

Archaeologists believe they may have discovered the birthplace of the legendary King Arthur at a Cornish palace. The palace in Tintagel is believed to have been built in the sixth century - around the time that the king may have lived. Researchers have uncovered 3ft (1 metre) thick palace walls and more than 150 fragments of ancient pottery and glass which had been imported from around the world.

Excavations have been taking place at the 13th century Tintagel Castle in Cornwall for five years in a project run by English Heritage. The castle is popularly thought to be the legendary birthplace of King Arthur, in part because of the discovery of a slate engraved with 'Artognou' which was found at the site in 1998. Geoffrey of Monmouth, a medieval historian, also claimed Tintagel was the birthplace of King Arthur in his book 'Historia Regum Britannae' - a history of British monarchs that some have called unreliable. This book was almost certainly completed by 1138 at a time when the Tintagel promontory, where the new palace has been discovered, was not inhabited. The medieval castle, that still stands today, was built almost 100 years later. The book suggests King Arthur was conceived after an affair between a king and the wife of a local ruler. Monmouth's assertion would likely have had to come from now long-lost earlier legends.

But it appears whoever lived at the site enjoyed a life of wealth and finery. More than 150 fragments of pottery and glass that had been imported to the site from exotic locations across the globe showed wealthy people lived there. These include Late-Roman amphorae, fragments of fine glass and a rim of Phocaean red-slip ware - the first shard of fine tableware ever discovered on the south side of the island. Archaeologists found evidence showing they drank wine from Turkey and olive oil from the Greek Aegean, using cups from France and plates made in North Africa.

Geophysical surveys carried out earlier this year found the walls and layers of buried buildings built between the 5th and 7th centuries. New excavations led by Cornwall Archaeological Unit (CAU) are shedding light on how and when the buildings were constructed. Researchers believe the 3 feet (one-metre) thick walls being unearthed are from a palace belonging to the rulers of the ancient south-west British kingdom of Dumnonia. The kingdom was centred in the area we now know as Devon, but included parts of modern Cornwall and Somerset, with its eastern boundary changing over time as the gradual westward expansion of the neighbouring Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex encroached on its territory.

"The discovery of high-status buildings - potentially a royal palace complex - at Tintagel is transforming our understanding of the site" said Win Scutt, English Heritage properties curator covering the West of England. "It is helping to reveal an intriguing picture of what life was like in a place of such importance in the historically little-known centuries following the collapse of Roman administration in Britain. This is the most significant archaeological project at Tintagel since the 1990s. The three week dig this summer is the first step in a five year research programme to answer some key questions about Tintagel. We'll be testing the dig sites to plan more advanced excavations next year, getting a much clearer picture of the footprint of early medieval buildings on the island, and gathering samples for analysis. It's when these samples are studied in the laboratory that the fun really starts, and we'll begin to unearth Tintagel's secrets."

This is the first time substantial buildings from the heart of the Dark Ages have been found in Britain. The Dark Ages is an imprecise period of time which describes the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. This means what the archaeologists have found is of major historical significance - irrespective of the potential connection to King Arthur. The facts around the real King Arthur are mired in myth and folklore, but historians believe he ruled Britain from the late 5th and early 6th centuries.

Who was King Arthur ?

The facts around the real King Arthur are mired in myth and folklore, but historians believe he ruled Britain from the late 5th and early 6th centuries. What is known is that during his reign as king he had to defend the land against Saxon invaders. He first appears in historical documents from the early 9th century, but much of what we know of the legendary king comes from the writings of Geoffrey Monmouth, who penned his history of Arthur in the 1100s. Links with the Holy Grail first appear in French accounts of the king, written circa 1180. Many historians agree that while the king was a genuine historical figure in early Britain, he could in fact be a composite of multiple people from an age of poor record keeping.

Tintagel Castle: steeped in legends of myth and magic

Tintagel Castle is a medieval fortification located on the peninsula of Tintagel Island, close to the village of Tintagel in Cornwall, England. The castle has a long association with the Arthurian legends, going back to the 12th century. In the 'Historia Regum Britanniae', a fictional account of British history written by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Tintagel is described as the place where Arthur was conceived. According to the tale, Arthur's father, King Uther Pendragon, was disguised by Merlin's sorcery to look like Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall and the husband of Ygerna, Arthur's mother. The book was extremely popular and other Arthurian tales were produced in the late medieval period which claimed the king was actually born at Tintagel. Merlin the magician was also said to live below the castle in a cave. In his Idylls of the King, Lord Alfred Tennyson also refers to the links between Tintagel and Arthur.

Despite these literary connections, no archaeologist has been able to find proof at the site that King Arthur existed or that the castle was linked to the legendary king. The archaeologist C A Ralegh Radford declared in 1935 that:

"No evidence whatsoever has been found to support the legendary connection of the Castle with King Arthur."

Many historians believe King Arthur was a completely mythical character, but others disagree, saying he may be based upon a British leader in the fifth century. In the 13th century, during the later medieval period, a castle was built on the site by Richard, Earl of Cornwall, which later fell into disrepair and ruin. Archaeologists in the 19th Century took interest in the site as it became a tourist attraction, with visitors coming to see the ruins of Richard's castle. Excavations in 1998 unearthed pottery from the 5th and 6th centuries at Tintagel Castle. Today Tintagel Castle is a popular tourist destination managed by English Heritage.

Did the legendary King Arthur really exist ?

Both the 'Historia Brittonum' (History of the Britons circa 828) and 'Annales Cambriae' (Welsh Annals circa mid-10th century), state that Arthur was a genuine historical figure, a Romano-British leader who fought against the invading Anglo-Saxons in the late 5th to early 6th century. The 9th Century 'Historia Brittonum' lists 12 battles that King Arthur fought, including the Battle of Mons Badonicus, where he is said to have killed 960 men - but some scholars have dismissed the reliability of this text.

Tintangel Castle is popularly thought to be the legendary birthplace of King Arthur based on the discovery of a slate engraved with 'Artognou' which was found at the site in 1998. Silchester was the site of King Arthur's coronation and was able to continuously defend itself against the Saxons. The Roman name for Silchester was Calleba - similar to the name given to Arthur's sword, Excalibur. One of Arthur's celebrated battles against the Saxons was fought at Chester or the City of the Legion, as it was known in the Dark Ages. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of battle at nearby Heronbridge, and recent excavations show the amphitheatre was fortified during this period, with a shrine to a Christian martyr at its centre. This fits a description of Arthur's Round Table, which was said to be a very large structure, seating 1,600 of his warriors.

During the 1960s, excavations by Philip Rahtz showed someone had inhabited the top of Glastonbury Tor during the so-called Arthurian period. According to the legends, this could have been King Meluas, who abducted Queen Guinevere to his castle at Glastonbury, or Arthur's warrior Gwynn ap Nudd, who was banished from his Palace on the Tor. In 1191, monks at Glastonbury Abbey found the body of a gigantic man, wounded several times in the head. The bones of his wife and a tress of her golden hair were also in the oak coffin.Found with the burial was an ancient lead cross, inscribed with:

"Here lies buried the famous king Arthur with Guinevere his second wife, in the Isle of Avalon."

In 1962, archaeological evidence was found supporting the story that a tomb within the ancient church had been disturbed centuries previously. The whereabouts of the cross and bones are no longer known. However, Arthur is not mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle or any documents written between 400 and 820 including Bede's 'Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum' (Ecclesiastical History of the English People circa 731).

"Royal palace discovered in area believed to be birthplace of King Arthur"

Daily Telegraph, 3rd August 2016

A royal palace has been discovered in the area reputed to be the birthplace of King Arthur. The palace discovered at Tintagel in Cornwall is believed to date from the sixth century - around the time that the legendary king may have lived. They believe the one-metre thick walls being unearthed are from a 6th century palace belonging to the rulers of the ancient south-west British kingdom of Dumnonia.

Excavations have been taking place at the site as part of a five-year research project being run by English Heritage at the 13th century Tintagel Castle in Cornwall to find out more about the historic site from the fifth to the seventh centuries. Using cutting edge techniques, Cornwall Archaeological Unit (CAU), part of Cornwall council, uncovered the walls of the palace and more than 150 fragments of pottery and glass which had been imported to the site from exotic locations across the globe indicating it was inhabited by wealthy individuals. Finds include sherds of imported late-Roman amphorae, fragments of fine glass, and the rim of a Phocaean red-slip ware which is the first piece of fine tableware found on the site. Made in western Turkey and dating from the 5th or 6th centuries, experts say it is the fragment of a bowl or a large dish which may have been used for sharing food during feasting. Win Scutt, English Heritage's properties curator for the West, said:

"This is the most significant archaeological project at Tintagel since the 1990s. The three-week dig is the first step in a five year research programme to answer some key questions about Tintagel and Cornwall's past. The discovery of high-status buildings - potentially a royal palace complex - at Tintagel is transforming our understanding of the site. We're cutting a small window into the site's history, to guide wider excavations next year. We'll also be gathering samples for analysis. It's when these samples are studied in the laboratory that the fun really starts, and we'll begin to unearth Tintagel's secrets."

The team dug four trenches in two previously unexcavated terrace areas of the island settlement and discovered buildings believed to date from the fifth centuries, when Romano-British rulers fought for control of the island against the Anglo-Saxon invaders. Geophysical surveys of the terraces earlier in the year detected the walls and layers of the buried buildings, and the archaeologists have discovered two rooms around 11 metres long and 4 metres wide.

Tintagel is one of Europe's most important archaeological sites. The remains of the castle, built in the 1230s and 1240s by Richard, Earl of Cornwall, brother of Henry III, stand on the site of an early Medieval settlement, where experts believe high-status leaders may have lived and traded with far-off shores, importing exotic goods and trading tin.

Previous excavations have uncovered thousands of pieces of pottery at Tintagel - with the vast majority dating from the fifth to seventh centuries and imported from the Mediterranean. The excavation team, directed by Jacky Nowakowski, principal archaeologist at CAU, is working with specialists from Historic England and geophysicists from TigerGeo Ltd. She said:

"CAU are very excited to be involved in English Heritage's research project at Tintagel. This new archaeological research project will investigate unexplored areas of the island in order to find out more about the character of the buildings on this significant post-Roman settlement at Tintagel. It is a great opportunity to shed new light on a familiar yet infinitely complex site where there is still much to learn and to contribute to active research of a major site of international significance in Cornwall. Our excavations are underway now, and will run both this summer and next, giving visitors the chance to see and hear at first hand new discoveries being made and share in the excitement of the excavations."

Excavations at Tintagel CastlePreviously researchers discovered a Roman amphitheatre in Chester which some experts believe was King Arthur's stronghold of Camelot.

The earliest accounts about King Arthur have come from the writings of the sixth century monk Gildas. A much fuller account of Arthur's life was written many centuries later by Geoffrey of Monmouth, which may have drawn on earlier sources but was suspected of being wildly embellished.

"A bridge fit for King Arthur: Breathtaking new footbridge planned for alleged birthplace of the legendary monarch is officially unveiled"

Daily Mail, 7th November 2016

Steeped in history, myth and folklore, it has been claimed the historic Tintagel Castle was the birthplace of King Arthur. And now the final CGI images have been unveiled for an imposing footbridge English Heritage plans to build at the historic fortification in Cornwall. The impressive structure will link the divided landscape of the famous site - but the £4 million project has caused controversy among historians who argue English Heritage is 'tampering' with Cornish history by trying to turn Tintagel Castle into a 'fairytale theme park' based on the legend of King Arthur.

The remains of the settlement can currently be seen on both the mainland and jagged headland which were once united by a narrow strip of land. The structure - made from a combination of steel, slate and oak wood - has been designed to follow the path of the original land bridge. The winning design by Ney & Partners Civil Engineers and William Matthews Associates has been selected from some 137 entries across 27 countries. It has gone on public display for the first time this week to test the public response. The bridge is due to be completed in 2019 - subject to planning and regulatory approval - and will be used by the castle's 200,000 annual visitors. English Heritage project manager Reuben Briggs said:

"There was a great deal of interest in the proposal to build a new bridge at Tintagel Castle when we announced the winner of our design competition in the spring. Over the seven months since then we have been conducting tests and investigations to ensure the proposed design would work and to minimise any potential impact on Tintagel's archaeology and ecology. Now we're inviting everyone interested in this project to come and view the proposals, hear about the results of our investigations and have their say on our plans. We hope anyone with an interest in this project will join us to find out more and to share their thoughts with us."

Winning planner William Matthews added:

"Tintagel Castle attracts visitors for many reasons: the dramatic landscapes and geological formations, the Dark Ages remains, the ruined 12th century castle and the legends of King Arthur and Tristan and Isolde. Together, they breathe an undeniable and powerful sense of life into the place - to be invited to contribute to that is a rare privilege and honour."

Other plans by English Heritage for further King Arthur attractions at the castle have attracted controversy. A group known as 'Kernow Matters To Us' expressed outrage when Merlin the Magician's face was engraved at the entrance to a rocky inlet near the castle earlier this year. A group of local historians accused the organisation of combining history with fantasy to promote its link with the king in a bid to drum up visitor numbers. The Cornwall Association of Local Historians, which has 200 members, said it was horrified that the head of the wizard Merlin has already been carved into a rock face at the medieval site.

"King Arthur's Legend" (February 2016) Miles Russell & Spencer Mizen, BBC History Magazine at pages 80 to 83

King Arthur. Heroic British warlord who led the fight against marauding Anglo-Saxons, or a figment of a writer's fertile imagination? It's a question that's been puzzling poets, chroniclers, historians and film-makers for more than 1,000 years.

And nowhere does this question have more resonance than on a small, wind-swept, rain-battered headland projecting into the sea off north Cornwall: Tintagel.

Numerous sites across north-west Europe - from Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset to the Forest of Paimpont in Brittany - have trumpeted their connections to King Arthur. Yet surely none are as intimately linked to the legendary warlord as Tintagel.

That this is the case is almost exclusively down to the endeavours of one man: a Welsh cleric going by the name of Geoffrey of Monmouth. In the 1130s, Geoffrey set about writing a history of the kings who had ruled the Britons over the preceding 2,000 years. The resulting Historia Regum Britanniae is among the greatest pieces of medieval history writing - though not an entirely reliable one. It tells us, for example, that Britain was founded by the Trojans, and introduces us to King Lear. Yet, most significant of all, says Miles Russell, senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology at Bournemouth University, is what it tells us about Arthur.

"In his Historia Regum Britanniae Geoffrey gathered together a series of legends from western Britain to come up with a single narrative of the past," says Miles. "So, in the case of Arthur, he related a tale that had been passed down by word of mouth through the generations. In this story, Uther Pendragon is besotted with Igraine, beautiful wife of Gor-lois, Duke of Cornwall. Uther is determined to have Igraine for himself and so, with the help of the wizard Merlin, assumes the image of Gorlois and tricks his way into Gorlois' castle at Tintagel. And it is here, Geoffrey tells us, that Arthur is conceived."

It's not hard to divine why Geoffrey chose Tintagel as the site of a key, dramatic scene in his retelling of a shadowy, mythical past. The modern world can seem a long way away when you venture out onto the island fortress on a dark winter's day the wind whipping around you and the sea raging below. Yet there's more to Tintagel's links to Dark Age Britain than atmosphere.

"Geoffrey's decision to choose Tintagel as the site of Arthur's conception would have been informed by history every bit as much as legend", says Miles. "We know that there was a lot of mining activity - primarily for tin - around here in the Iron Age. And, as Tintagel is such a dominant part of the local landscape, it's more than possible that there was an Iron Age fort up here - perhaps ruled by an Arthur-like warlord."

What's beyond dispute is that, by the sixth century, Tintagel was a bustling port - a key link in a thriving trade network that stretched from southern Britain down the Atlantic seaboard to the Mediterranean coastline.

"You would have had ships coming in here from all over southern Europe to buy tin and copper," says Miles, "and, in return, they brought with them exotic goods such as wine and olive oil".

That this is the case is attested by the hundreds of pieces of fifth to seventh-century pottery that have been discovered all over the island. Faint remains of what is thought to have been the residence of a Dark Age ruler also suggest that Tintagel was a site of some importance.

Yet, following its brief heyday, Tintagel slipped back into obscurity - a draughty outpost on the edge of the kingdom. And there it probably would have stayed if it hadn't been for the arrival on the headland of Earl Richard of Cornwall - brother of King Henry III - in the early 13th century.

The great building project that Richard initiated here in the 1230s still dominates Tintagel today. At its centrepiece is his castle and, though it's now nothing more than a ruin, much of Richard's handiwork - including two courtyards, a curtain wall and a gate tower - continue to defy everything that the Cornish weather can throw at them. But the question is, why did Richard choose to build at Tintagel?

"Like many Norman aristocrats, Richard was entranced by the romance of the Arthur legend," says Miles. "So when he decided to set up residence in northern Cornwall, what better way of establishing a bond with a heroic, Dark Age warlord - and, in doing so, effectively controlling the Cornish people - than by choosing the site where Arthur was conceived? For Richard, building a castle at Tintagel was a canny political move."

Richard's desperation to establish himself as a latter-day Arthur is even reflected in the design of the castle itself.

"Its walls are thin, and it's built out of slate in a mock antiquated style," says Miles. "This tells us that Richard wasn't attempting to build a highly defensible stronghold but a romantic building that harks back to Arthur - part of what you could call a medieval theme park."

If Richard was obsessed with King Arthur, he was far from alone. Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae was hugely popular in the Middle Ages - and Arthur was its most feted hero.

"The Normans loved Arthur, and that's partly because he is said to have defeated the Anglo-Saxons, just like they'd done," says Miles. "By identifying with Arthur, the Normans were saying: 'We've got a kinship with an ancient line of British kings, so don't dare question our legitimacy.' You can see this in Henry II's decision to commission Glastonbury's monks to excavate the supposed graves of Arthur and Guinevere."

Polite society

Yet the real genius of Geoffrey of Monmouth's text is that it transformed a blood-soaked warlord, battling through the mud of western Britain into a universal hero, celebrated in polite society across Europe. Within decades, Arthur was being championed as a Christian hero during the crusades and celebrated as an icon of knightly chivalry by French writers. And this, says Miles, was a phenomenon with staying power.

"More than 300 years after Geoffrey died, Henry VII named his eldest son Arthur to bolster his hold on the English throne. Henry VIII even used the Arthur legend - and its link to a form of British Christianity that predates the papacy - to justify his break with Rome."

But beneath the chivalry, the romance, and the political agendas, there remain questions: Where did the idea of King Arthur come from? Could the legend be based on a historical figure?

"The trouble with this is that it takes us back to one of the most shadowy eras in British history - the chaotic, confused period that would have followed the departure of the Romans," says Miles Russell. "Sure, there could have been a king going by the name of Arthur - this was, after all, a time of warlords, of kingdom fighting kingdom, of the Anglo-Saxon invasion. Yet the reality is that, such is the dearth of evidence, we can never know. There is, for example, no earliest primary source that we can say contains the first secure reference to Arthur. A poem called The Gododdin, possibly from AD 600, compares one of its lead characters to Arthur, which suggests that he may have existed as a model of heroism by the start of the seventh century."

"But the fact is, Geoffrey of Monmouth's Arthur is a composite character. He's created from multiple different heroes. There could be elements of Magnus Maximus - the Roman commander of Britain who led a massive rebellion against the emperor Gratian. Then there's a British general called Ambrosius Aurelianus. He is a prominent figure in the writings of a sixth-century British monk called Gildas, who described how Aurelianus defeated the English at a great (and seemingly historical) battle at a place called Badon."

Could this English-slaying freedom fighter have been the primary inspiration for the mythical figure that became King Arthur? Again, we may never know. But the fact that men such as Aurelianus lived in the period following Rome's fall - an age when Tintagel was a thriving port and probably a power base - only serves to strengthen the site's association with Arthur.

And it is an association that has drawn visitors to Tintagel for centuries. After Earl Richard's death, the island-fortress went into a long decline and the castle became a romantic ruin. That's how it stayed until the 18th and 19th centuries when a series of artists such as Alfred Tennyson - fired up by a renaissance in interest in ancient Britain - began championing Tintagel's connections to the Arthurian legend through paintings and literature. By the end of the 19th century, tourists were flocking here to witness 'Arthur's castle' and 'Merlin's cave'.

Celebrated creation

While most modern historians agree that it is simply impossible to establish a historical link between Tintagel and Geoffrey of Monmouth's most celebrated creation, those tourists keep coming. Tintagel is now one of English Heritage's top five attractions, drawing up to 3,000 visitors a day in the peak summer season.

With a new outdoor interpretation of Arthur's legend (featuring interactive exhibits and artworks) set to be unveiled in 2016, and plans in place to build a new, 72-metre-long footbridge to link the mainland with the island in 2019, the future is looking bright for this Dark Age site. And that, says Miles Russell, is also the case for Arthur.

"He's moved beyond his status as an obscure British king to one of the world's great mythological figures, and so there will always be another element of his legend that can be drawn out. I don't think his story will ever end".

King Arthur: 5 more places to explore

- Cadbury Castle, Somerset, where an ancient fort was upgraded. This Iron Age fortress was first linked with Arthur in 1542, when the antiquary John Leland claimed that Cadbury had been 'Camelot'. Excavations here in the late 1960s demonstrated that there was indeed significant remodification of the prehistoric fort in the post Roman period, but whether this was the headquarters of a monarch who inspired the myth of Arthur is unknown.

- Glastonbury Abbey, Somerset, where 'Arthur' was reburied. Glastonbury today has strong popular associations with King Arthur. This is in part due to the romantic setting of both the ruined abbey and the Tor, but also because it was here, in 1191, that monks disturbed two graves, supposedly those of Arthur and Guinevere, establishing Glastonbury as 'Avalon'. The bones were reburied by the high altar, providing a lucrative pilgrimage attraction.

- The Great Hall, Winchester, where a round table hangs. On the wall of the Great Hall of Winchester hangs a large round table. The round table was added to Arthur's story in the 12th century, and has become a potent aspect of the myth. Dendrochronology suggests that it dates from the late 13th century and it may have been commissioned by Edward I, who was a great Arthur enthusiast.

- Caerleon, Gwent, Where Arthur may have won a battle. Geoffrey of Monmouth, who may have grown up nearby, frequently mentions Caerleon's Roman legionary fortress in the Historia Regum Britanniae, describing it as a powerful city in Arthur's time. Caerleon could also be the 'City of the Legions', one of the many victories in battle credited to Arthur.

- Birdoswald, Cumbria, where it's claimed Arthur was slain. Birdoswald was the Roman fort of Banna, an outpost at the western end of Hadrian's Wall. Some have suggested that the fort provided the basis for the battle of Camlann, where Arthur fell in battle fighting the treacherous Mordred but, as with all things Arthurian, this is much disputed.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology with over 30 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. He graduated from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London in 1988 and worked as a field officer for the UCL Field Archaeology Unit and as a project manager for the Oxford Archaeological Unit, joining Bournemouth University in 1993. He has conducted fieldwork in England, Wales, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Germany, Sicily and Russia. He is currently director of Regnum and co-director of the Durotriges Project, both investigating the transition from the Iron Age to Roman period across south-east and south-west Britain. He gained his doctorate, on Neolithic monumental architecture, in 2000 and was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2006. Miles is a regular contributor to television and radio, his most recent appearances being in Time Team, Time Team: Big Roman Dig, Timewatch, The Seven Ages of Britain, Landscape Mysteries, The One Show, Digging for Britain, Witness, Rome's Lost Legion, Operation Stonehenge: what lies beneath, Discovery, A History of Ancient Britain, The Big Spring Clean, Making History, The Sacred Landscapes of Britain, Border Country: the story of Britain's lost Middleland, Secrets from the Sky and Underground Britain.

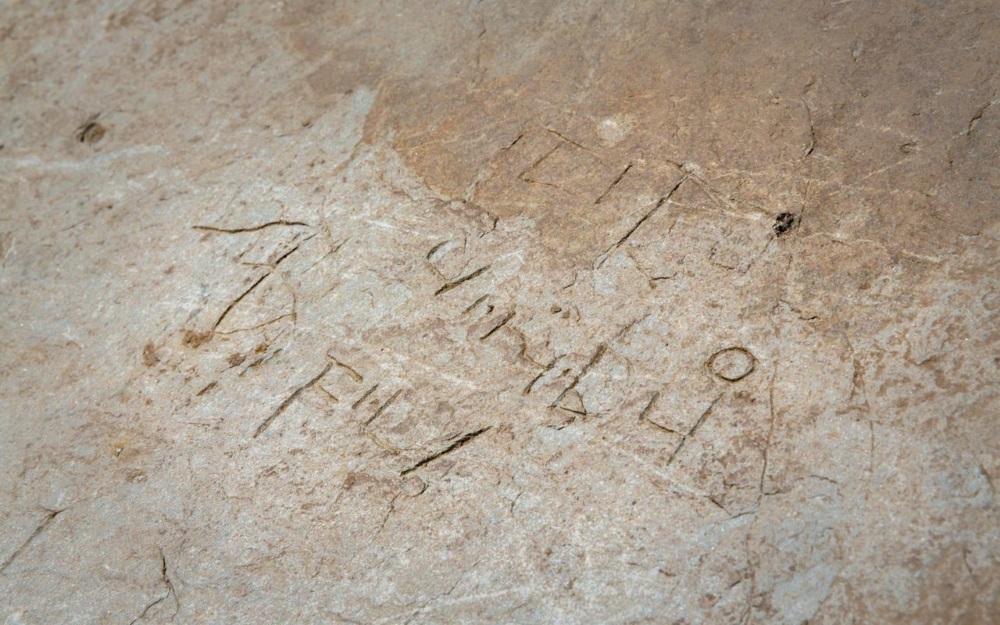

"Ancient doodle discovered on windowsill at Tintagel Castle is evidence of 'King Arthur's court'"

The Telegraph, 15th June 2018

For centuries, historians have searched for evidence that Tintagel Castle was the birthplace of King Arthur.

Perched on a rocky outcrop on the Cornish coast, the windswept site seemed an unlikely location for a royal court. But the discovery of a 1300-year-old windowsill has lent credence to the idea that Tintagel was, after all, the home of kings.

The two-foot long slate bears a mix of Latin and Greek with Christian symbols, in a decorative script similar to those found in illuminated Gospel manuscripts of the time, showing that the writer was familiar with those texts.

English Heritage, which manages Tintagel, said the find "lends further weight to the theory that Tintagel was a royal site with a literate Christian culture".

The writing is believed to have been the work of someone practising their handwriting, perhaps carving words into the stone while gazing out to sea. It includes the Roman and Celtic names "Tito" and "Budic", and the Latin words "fili", or son, and "viri duo", meaning "two men". The Greek letter delta also appears.

The discovery will delight those who believe in the Arthurian legend, which has made Tintagel a popular tourist attraction, although for naysayers it provides no more concrete evidence that Arthur actually existed.