Index

- Background: Spring and Summer 1915

- The Second Action of Givenchy

- The First Attack on Bellewaarde

- The Actions of Hooge: Summary

- Analysis

- Casualties

- Hooge

- 6th Battalion the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

- Edmund Blunden

- The Riddle of the Rhine Chemical Strategy in Peace and War

- Hooge Crater Museum

- Frontline Hooge Museum

Background: Spring and Summer 1915

From the closing May days of the Battles of Ypres and Festubert, until the September opening of the Battle of Loos and the French attacks in Champagne, there was no general change in the situation on the Western Front. It was a period of static warfare, where the Army suffered average losses of 300 men a day from sniping and shellfire, while they continued to gradually improve and consolidate the trenches. Both sides increased the tempo of underground mine warfare, which was feared greatly by the infantry in the front positions.

At the request of French Commander-in-Chief Joffre, on the 7th to 8th June 1915, the British Second Army extended its left to Boesinghe, thus placing it for the first time in complete occupation of the Ypres salient. Late in May, the First Army also extended, southwards 5 miles from Cuinchy towards Lens. During August the Third Army was formed, taking over a 15-mile front from Curlu to Hébuterne, on the Somme. Further discussions about Allied dispositions and strategy took place at the 1st Inter-Allied Military Conference on 7th July 1915.

The Army continued to suffer from a shortage of material, notably heavy artillery and machine guns (although Lewis guns were officially issued from 14th July onward). Sir John French issued general orders to First Army to the effect that operations be limited to 'small aggressive threats which will not require much ammunition or many troops'.

Three New Army Divisions arrived during May: the 9th (Scottish), the 12th (Eastern) and the 14th (Light). Thirteen more were to arrive during the months July to September, including the 2nd Canadian. No development of a reserve was possible, the new units serving only to enable the extensions of the line held by the British Army.

Army Staffs issued new training doctrines in the instructional pamphlets "The Training of Divisions for Offensive Action", and "The Training and Employment of Bombers", amongst others.

The Second Action of Givenchy

Joffre was planning to renew the attack in Artois on 2nd June; the British would need to support by making a flank attack near Haisnes or Loos. However the Loos battlefield was dominated from the high ground near Violaines north of the La Bassée Canal. It was decided that IV Corps under Rawlinson would attack on the front between Chapelle St. Roch and Rue d'Ouvert, on 11th June, with the intention of seizing these heights. The action was postponed as it was learned that the French would not be ready for their attack until the 16th.

The attack was to be carried out by the 7th and 51st (Highland) Divisions, with the Canadian Division forming a defensive flank near the Canal. It was preceded by 48 hours slow bombardment, aimed at destroying trenches and wire; a heavier 12-hour fire would precede the infantry assault. Great attention was paid to air co-operation and observation, largely to ensure economy of use of ammunition.

The infantry advanced at 5.58pm on 15th June 1915, just after miners of the 176th Tunnelling Company RE had blown a 3,000 lb mine under the Duck's Bill position. There was no surprise, and the German trenches had hardly suffered. The leading 21st Brigade and 154th Brigade suffered heavy casualties from shelling, machine-gun and rifle fire, yet managed to enter the enemy front line in several places.

It proved virtually impossible to reinforce this minor success, as no man's land became swept by constant and heavy fire. Under pressure from the French, whose own attack was faltering, the British attack was repeated at 4.45pm on the 16th June, this time with a bombardment of only 2 hours which was all that shell supply could provide. The results were much the same. By the 18th, all the small gains had been relinquished: next day, Joffre ended the Second Battle of Artois.

The First Attack on Bellewaarde

A minor operation was planned to coincide with the attack at Givenchy, aimed at gaining ground to the Eastern side of the Bellewaarde lake, which enjoyed good observation over the British lines East of Ypres. V Corps (Allenby), which consisted of 3rd and 5th (Northumbrian) Divisions, with two Brigades of the 14th (Light) Division. Lessons previously learned were used: telephone lines were laid in triplicate in different routes, up to 6 feet deep; a system of visual signalling and a pigeon service was also prepared. High Explosive shell was used to cut enemy wire, and was effective. Eight lines of jumping-off trenches were dug behind the front line (unfortunately they were in full view of the enemy, and were heavily shelled). The 9th and 7th Brigades of the 3rd Division were to lead the attack. The first objective was the enemy front line; the second the Hooge to Bellewaarde Farm track; the final one the lake edge.

A bombardment of only 105 minutes preceded the advance at 4.15am. The first objective was soon gained - in fact so vigorous was the attack, with the second and third waves joining in, that the infantry ran into their own barrage. Trenches filled with men, units became mixed up and all control over the action was lost. The second line was reached, soon after which a strong German counterattack was repulsed. By 9.30am, the advanced parties were still under British shell fire and they retired to the German front line.

The 42nd Brigade of the 14th Division was ordered to push the attack forward after a fresh bombardment, at 3.30pm, but its movement to the front was delayed by a heavy German barrage. The main body did not get into position until 4pm, by which time only two battalions of 7th Brigade had actually attacked. This (made by 3rd Worcesters and 7th Royal Irish Rifles) was met by heavy machine-gun and artillery fire. By 6pm it was decided to consolidate the ground won, and to halt further attacks.

The Actions of Hooge: Summary

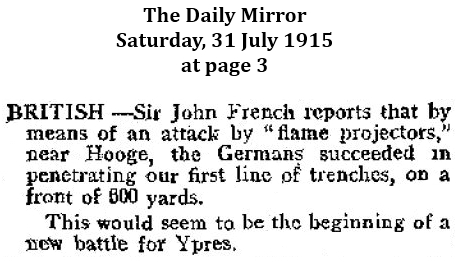

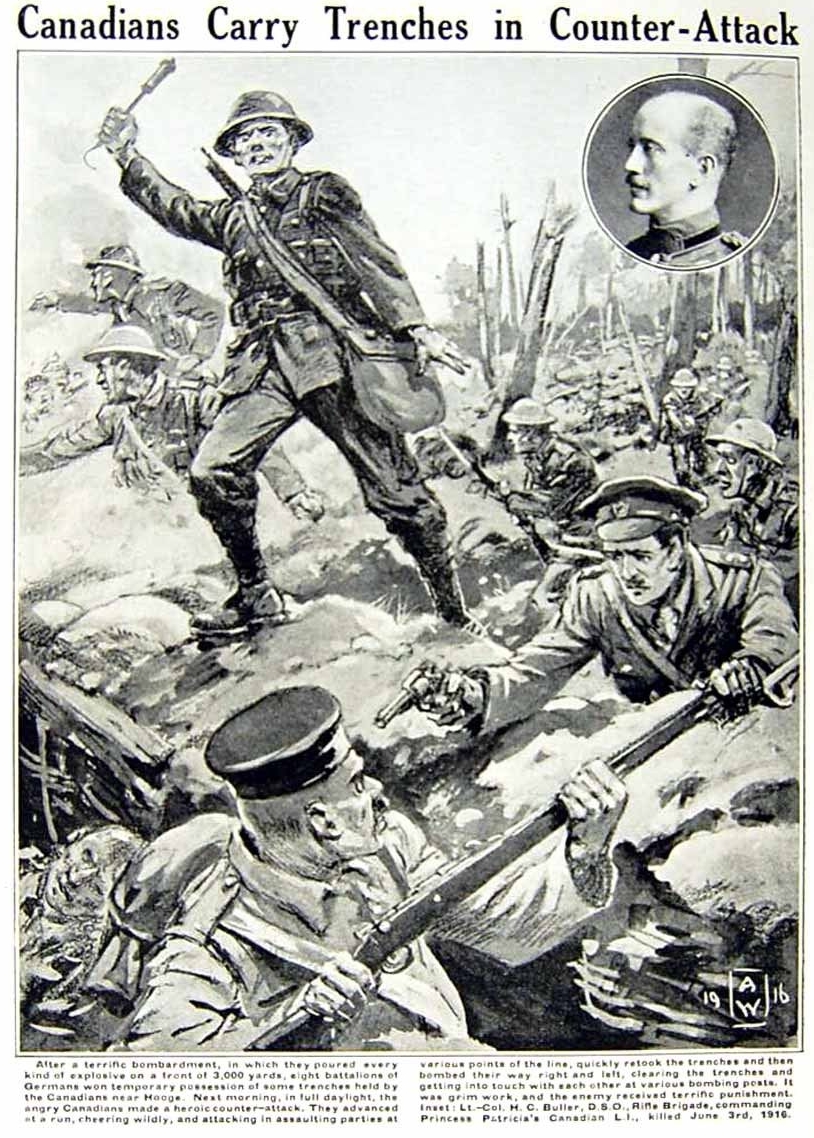

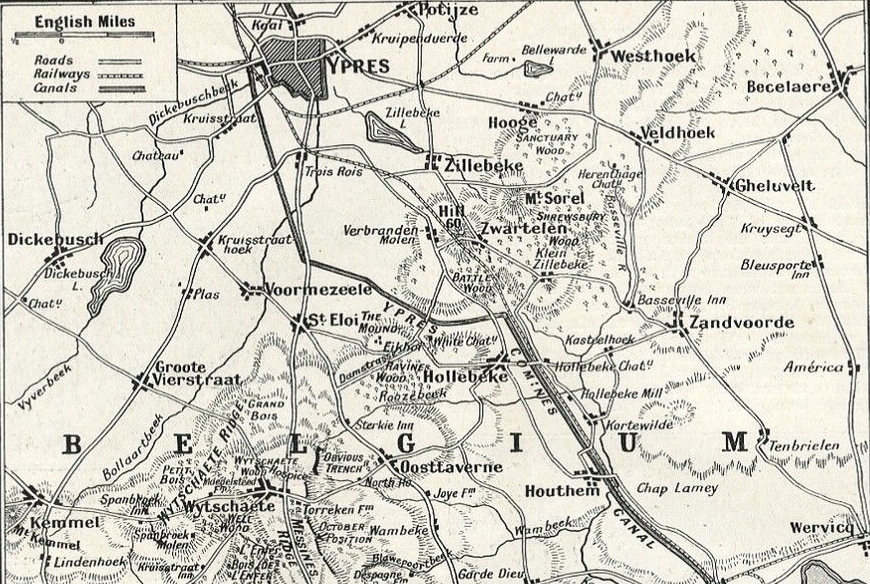

On 2nd June 1915, a severe German bombardment from 5am to noon, followed by an infantry attack from the Northeast, led to the loss of the ruins of the Chateau and Stables. At this time the position had been occupied by regiments of the 3rd Cavalry Division. During the evening, two Companies of the 1st Lincolns and one of the 4th Royal Fusiliers of 9th Brigade of the 3rd Division counter attacked and successfully recovered the Stables.

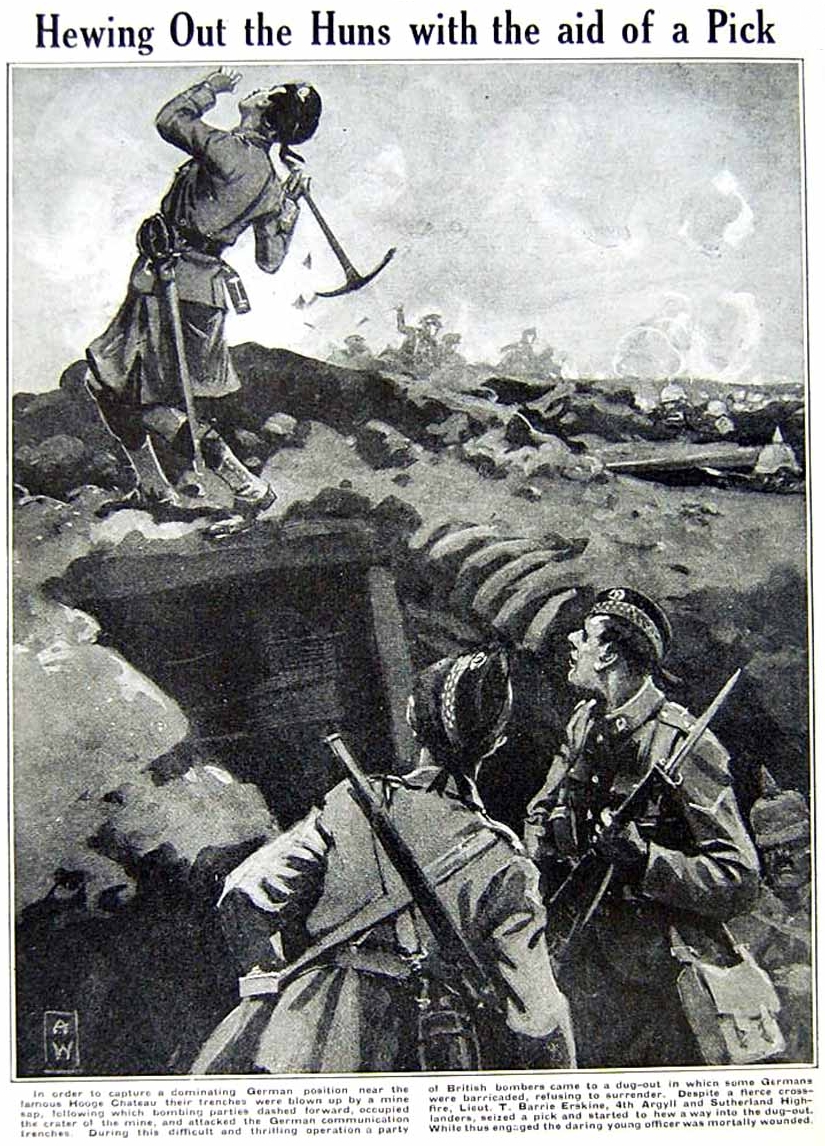

At 7pm on 19th July 1915, a large mine was exploded by 175th Tunnelling Company RE, under a German trench position. The spoil from the detonation threw up a lip 15 feet high, around a crater 20 feet deep and 120 feet wide. After the firing, it was immediately occupied by two Companies of the 4th Middlesex (8th Brigade, 3rd Division). British artillery quelled all signs of German attempts to recover the crater.

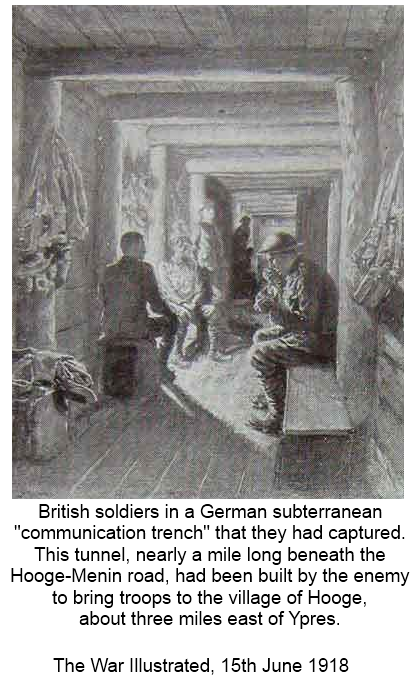

German retaliation came on 30th July 1915. The Hooge sector was being held by 41st Brigade of 14th Division, which had taken over the area only a week before. The 8th Rifle Brigade held the near crater lip, with the 7th KRRC on their right, across the road. These battalions had relieved the others of the Brigade during the night. At 3.15am, with dramatic suddenness, the ruins of the Stables were blown up, and jets of flame shot across from the German trenches. This was the first time in warfare that liquid fire flamethrowers had been used by the Germans against the British. Immediately a deluge of fire of all kinds fell on the Brigade, and on all support positions back to Zouave Wood and Sanctuary Wood. The ramparts of Ypres and the exits from the town were also shelled.

The Germans achieved complete surprise, but although the British front lines were evacuated, they did not follow beyond them. There was intensive hand to hand fighting in some trenches; eventually virtually all of the positions held by the Brigade were lost. The 42nd Brigade on the left was not attacked, and the left Battalion of the 46th Division on the right held on. Division rushed up reinforcements, and a new line along the edge of the woods was formed. At 11.30am, orders were issued for a counterattack by the 41st and 42nd Brigades. A feeble 45 minute bombardment preceded this. The 41st Division attack at 2.45pm, by the 6th DCLI, failed, with no man approaching closer than 150 yards the new German positions; the 9th KRRC of the 42nd fared better and recovered some of the lost lines. The 43rd Brigade relieved the badly-hit 41st during the late afternoon and evening. During the night, another flamethrower attack was repulsed, but further efforts by the 14th Division on the 31st came to nothing against heavy German shellfire.

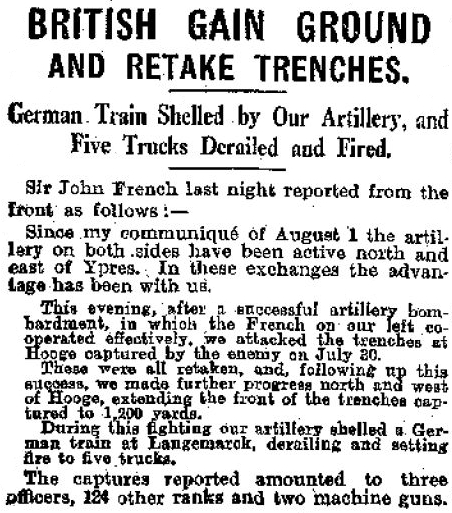

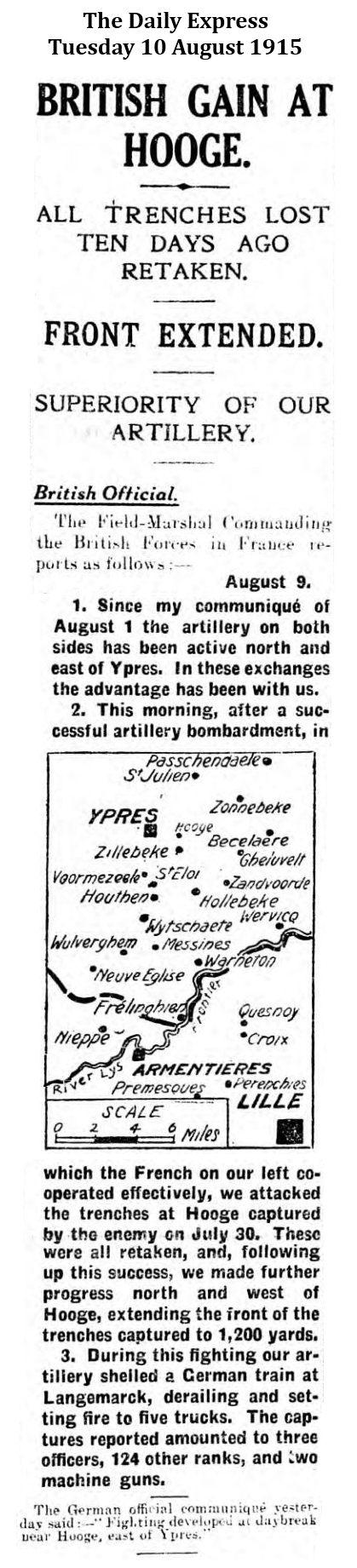

A surprise attack by 6th Division on 9th August 1915 regained all of the ground lost, including the ruins of the Chateau Stables.

Casualties

At Givenchy, IV Corps suffered over 2,700 casualties. At Bellewaarde, the 3rd Division alone lost over 3,500. Both attacks were characterised by very high losses among officers and senior NCOs. The 14th Division lost just under 2,500 on 30th July at Hooge.

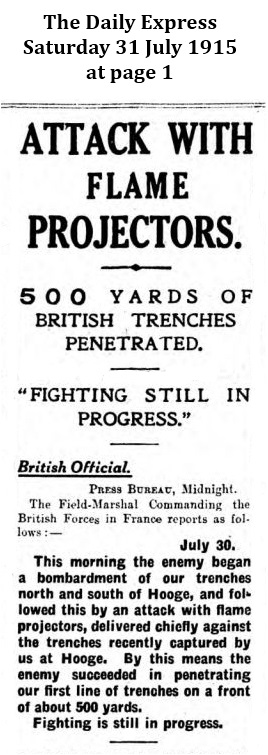

TIDINGS WANTED

Stocking - No 1961. A/Corporal Charles Stocking,

O Company, 8th Rifle Brigade, 41st Infantry Brigade,

14th Division. Reported wounded and missing

night of liquid fire attack at Hooge on July 30.

Mother anxiously seeks news.

100 Chaseside, Old Southgate, London N.

Analysis

- no significant gains of ground or improvement of the tactical positions was achieved

- the losses of officers and NCOs was to hurt the British Army badly in the coming months

- the surprise deployment of a new military technology (flame-throwers) gained little of significance for the German Army

- lines of infantry, attacking "over the top" into unassailable machine guns proved to be a poorly planned and highly questionable strategy

- the participants fought gallantly and with heavy losses, to little avail

Hooge

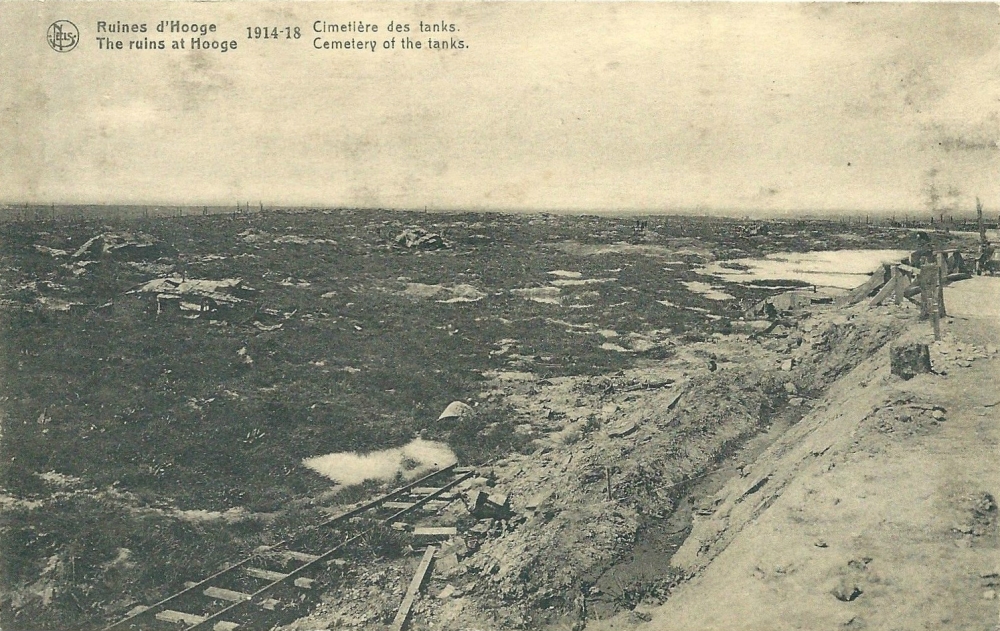

Hooge ('high' in Flemish/Dutch) was where the Germans chose to launch their first attack against the British aided by the use of flamethrowers; they had used them on a number of other occasions against the French. They were highly successful at Hooge, and caused much confusion and panic amongst the British defenders. The Germans launched their attack at the end of July 1915, with the aim of establishing control over the remaining dominant ground held by the British in the area around Hooge Chateau.

The rigorous German pressure on the British in their crater continued, making it untenable. Apologies for trenches, damaged by the incessant shell fire, ran up to the lip on either side, but with no definite connection between them around the crater (the original defence was essentially a sandwich of sandbags in which the British sat). The relief of battalions was allowed to go undisturbed, despite the extreme proximity of the trenches in places, so that bombs could have wrought great damage, especially in the confusion of the hand over. This was ominous. Stand to - the practice of all men equipping themselves with their kit and manning their posts ready to expel an attack - took place as customary half an hour before dawn. The men would expect to hold this position for an hour or so - the most vulnerable time in the trenches, when the enemy might be expected to use the tricks of light at this time to effect a surprise.

Streams of liquid death spat out from the German lines on the morning of 30 July 1915

heralding an assault on the British positions around Hooge

At 3:15 am on Friday, 30 July 1915 the Germans (Württemberg Infanterie-Regiment 126, part of the 39th (Alsatian) Infanterie-Division) launched their attack. The remnants of the stables were blown up, whilst simultaneously men of the 8th Rifle Brigade (at battalion strength) were subject to jets of flame streaming from the German parapets rather like water might come from a large hose. At the same time a massive bombardment of shells and mortars, grenades and machine-guns was opened on the communication trenches and the 300 yards or so of ground between the front line and the support lines in Zouave and Sanctuary Woods.

|

|

The defenders were hustled from their trenches; but the Germans stopped immediately to consolidate their position, and tried to extend it eastwards by launching an all-out assault on the 7th King's Royal Rifle Corps (also a battalion), which unit eventually succumbed to the pressure and surrendered most of its trenches. Further south 1/8th Sherwood Foresters was attacked, but managed to hold on to its position to the north of Sanctuary Wood. Not a single "flame thrower pioneer" died in combat or of wounds in that attack, described in the 2 August edition of the (London) Daily Chronicle as "The Flame Fight".

Counter attacks were launched as soon as practicable, in this case at 2:45 pm; always a feature of the Great War, and often questioned nowadays, the purpose behind such attacks was that the enemy should be attacked whilst he was off balance and prevented from settling into his new position. In this case they were partially successful, 9th King's Royal Rifle Corps regaining some trenches; but the attack from the south failed dismally, men not getting within 150 yards of the new German positions.

One of the casualties was Lieutenant Gilbert Talbot, now buried at Sanctuary Wood Cemetery. A member of 7th Rifle Brigade, his battalion counter-attacked from Zouave Wood. The Battalion War Diary comments on 31st July:

"A correct casualty list is very hard to prepare without details from the Clearing Stations and owing to many being killed and wounded beyond reach."

Talbot's Company (C) attacked to the left of the Old Bond Street communication trench. The War Diary has him listed as "missing believed killed". Subsequently a note has been added, "Body found. Killed." Doubtless his was one of the many bodies recovered when the line was recaptured on 9th August. For the moment the British licked their wounds and planned their next move.

C Company of 8th Rifle Brigade, to the right of the crater, seemed to have been almost completely obliterated very early on in the attack. 8th Rifle Brigade went into the line with 24 officers and 745 other ranks; it lost 19 officers and 469 other ranks killed, wounded and missing.

The 7th King's Royal Rifle Corps held the line near the stables, running south to Sanctuary Wood. The flamethrower attack was not directed specifically at them, though the position held near the stables did suffer from the extreme easterly part of the seeming wall of flame and clouds of smoke. An attack against the trenches to the south of the Menin road from the east was quickly suppressed by defensive fire, but were then subjected to very heavy machine-gun and shell fire. What did happen, though, was that the Germans who had captured the crater area now poured over the Menin road and attacked the G3 trenches in the rear and from the south. Meanwhile, further south, just above Sanctuary Wood, the Germans launched a flamethrower attack on G1 and a very exposed position - the Sap. However, the Germans who attempted to rush across the 20 yards between the trenches succumbed to the fire from the British. They tried once more with bombs, but once more failed.

Meanwhile, in the complex of trenches between Zouave and Sanctuary Woods scenes of extraordinary chaos and individual initiative were taking place as bombing and counter-bombing took place, with even a spare group of Royal Engineers being thrown into the fray.

One can only feel sorry for the two battalions that had been relieved earlier - 8th King's Royal Rifle Corps and 7th Rifle Brigade. 7th Rifle Brigade had only reached its rest billets at Vlamertinge (several kilometres to the west of Ypres) at 3:45 am; at 4:45 am it was put on the alert, and by 5:30 am they were ordered back to Ypres - tired, unwashed, not fed or rested, and probably with a clear idea of what was likely to be in store for them. 7th King's Royal Rifle Corps was eventually forced to retire back to the northern edge of the woods, having spent almost the whole day being fired at from front, back and flanks by all manner of weapons.

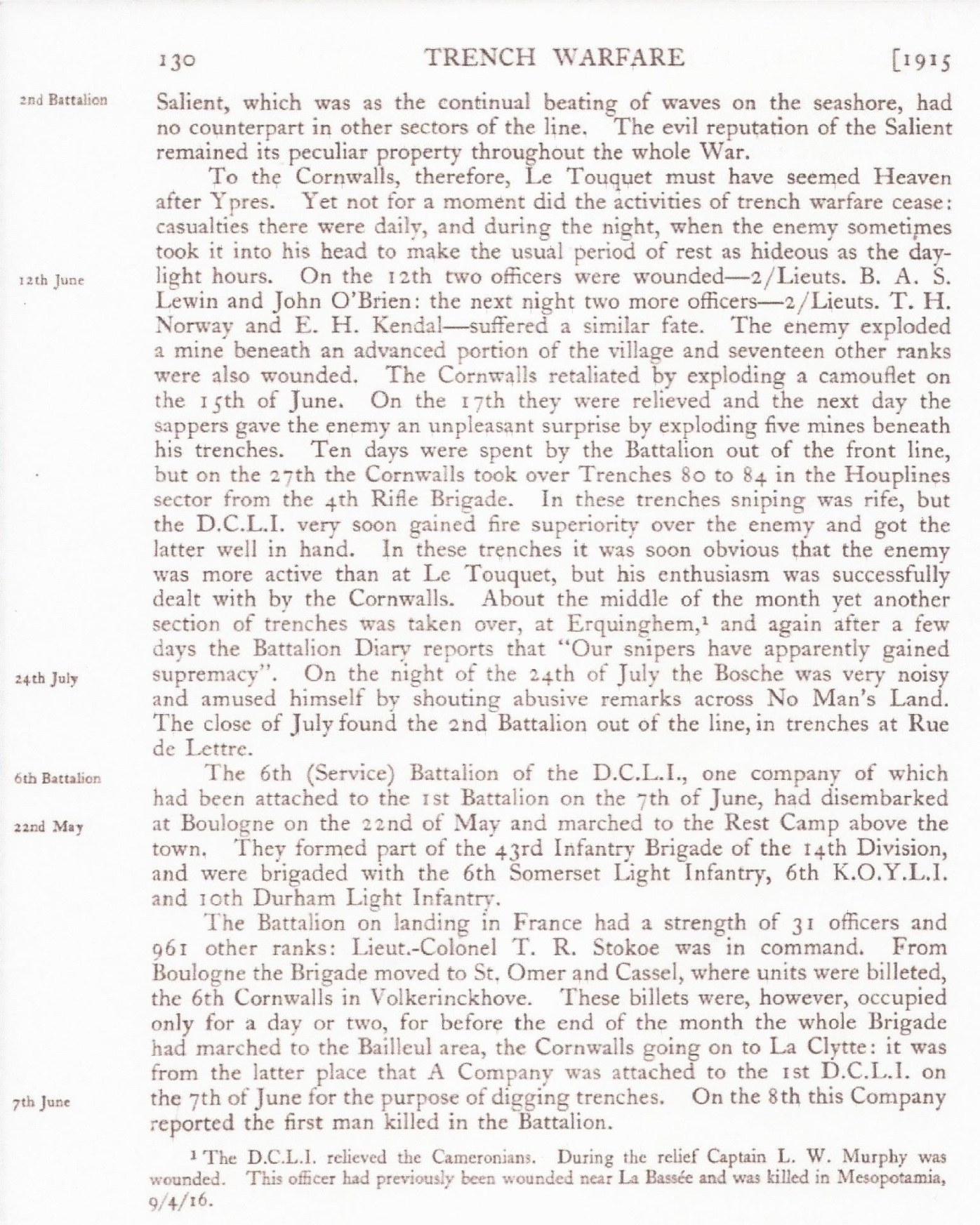

6th Battalion the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

Various battalions were rushed up to hold the line, amongst them the 6th Battalion the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry (DCLI). Their part in the holding battle was told in a letter from the adjutant, Lieutenant Blagrove (killed in action on 12th August 1915), to his commanding officer, Colonel Stokoe, who had been wounded a few days earlier. The Battalion's task was to secure the front in the northern fringes of the Sanctuary and Zouave Woods.

"They lined Zouave Wood and held it. They were grand, and nothing could move them. At dusk (of 30th July) the battle ended for a while. The Germans lined the high ground facing us, and completely commanded us at about 300 yards. We were really in an impossible position, but were ordered to hold on at all costs.

At about 2 am next morning in the dark the Germans tried to bomb us out of the two trenches leading from us to them (old communication trenches). The artillery on both sides opened rapid fire, the din was awful. The Germans then used liquid fire but fortunately failed to get any into the trenches. Our men were dropping in all directions, and I am grieved to say the following officers were killed - Aston, Hulton-Sams, Challoner, Birch and the Doctor (McCallum). The only thing that will comfort you (and which does comfort those of us who survive) is that our men were glorious and, even though the Durhams fell back on our left, they held their ground. We were in this woeful position all the following day - the 31st - and were crumped from three directions all the time. We had no food or water for forty-eight hours.

One incident I must tell you. When they used some liquid fire some of C Company (whose officers and NCOs were all knocked out) broke from about 30 yards of front and fell back (small blame to them). The machine-gunners (under Sergeant Silver) who were just in the rear, yelled to them that if they did not go back to the line they would open fire on them and that the 6th Cornwall's were going to "bloody well stick it". So the few men of C Company re-occupied their line of trench."

The above account is an excerpt from "The History of the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, 1914-1919", 1932, E. Wyrall at pages 130 to 136

The following 50 non-commissioned ranks of the 6th Battalion DCLI were either killed in action ("kia") or died subsequently of their wounds received in the liquid fire attack ("dow"):

| Name | Rank | Serial Number | Killed in Action (kia) Died of Wounds (dow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Henry Bakes | Corporal | 12366 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Richard Brenton Bate | Private | 17189 | 31 July 1915 (dow) |

| George Bond | Private | 10457 | 1 August 1915 (dow) |

| Martin Orme Bowman | Sergeant | 12467 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Edward Carlyle | Private | 12350 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Leopold Macdonald Castle | Sergeant | 11380 | 3 August 1915 (dow) |

| George William Chappell | Private | 10977 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Horace Henry Currey | Private | 3/5918 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Arthur Davis | Private | 10444 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Ephrain Dunstan | Private | 10483 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Dennis Alfred Earl | Private | 13880 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Henry Few | Private | 10758 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Henry Ford | Private | 10931 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Edward Hammett | Lance Corporal | 12382 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Ernest Holloway | Private | 3/5442 | 1 August 1915 (dow) |

| Leonard David Ivory | Private | 12875 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Albert Jackson | Private | 18627 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Richard George Jacobs | Private | 11478 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Arthur Edward Jones | Lance Corporal | 10771 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Thomas Kelleher | Private | 10494 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Frank King | Private | 12038 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Joseph Lee | Private | 12447 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Horace Frederick Martin | Private | 12290 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| William Henry Martin | Private | 17200 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Albert May | Private | 10640 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Samuel Maynard | Private | 11925 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| John Henry Melaney | Private | 10625 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Walter Harper Murphy | Private | 10622 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Edward Ewart Nott | Private | 19665 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Cyril Horace Orman | Private | 11462 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Fred Parton | Private | 11266 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Robert Parsons | Lance Corporal | 10614 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Charles Pearce | Private | 17179 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Charles Alfred Phelps | Warrant Officer Class II | 3/5981 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Walter James Pratt | Lance Corporal | 14846 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Wilfred Purbrick | Private | 11763 | 4 August 1915 (dow) |

| Arthur Quinlin | Private | 3/5757 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Harry Redding | Private | 8424 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Percy George Rowley | Private | 13010 | 1 August 1915 (kia) |

| Joseph Salisbury | Private | 15549 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| John Saunders | Private | 11714 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Arthur Sayer | Lance Sergeant | 10845 | 1 August 1915 (dow) |

| Charles Alfred Searle | Private | 11757 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Abrahan Simmonds | Corporal | 16171 | 30 July 1915 (kia) |

| Cecil Henry Snow | Private | 10911 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Charles Edward Towner | Private | 11723 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

| Sidney James Turle | Private | 17169 | 1 August 1915 (dow) |

| William Webster | Lance Corporal | 11185 | 2 August 1915 (dow) |

| Maurice Williams | Corporal | 11286 | 30 July 1915 (dow) |

| George Daniel Wright | Private | 11692 | 31 July 1915 (kia) |

Lieutenant Blagrove was killed on 12 August 1915 whilst trying to rescue men from the cellars of the cloisters of St Martin's Cathedral in Ypres - men trapped by a deluge of shells. After the war the bodies of some 40 soldiers were discovered in a cellar under the Cloth Hall. They were men of B Company 6th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, killed as a result of this bombardment.

Reservoir Cemetery is the largest cemetery in Ypres and is located in the north-west of the town adjacent to an Advanced Dressing Station where many casualties transferred from the front lines were buried. The cemetery was begun in October 1915, and used from then on throughout the war, and contained around 1,100 graves after the Armistice. It now contains 2,613 graves, over 1,000 of which are unidentified. The register records the graves of the men in Plot 5 Row AA being those of 16 soldiers from the 6th Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry who were killed on the 12th of August 1915. They were billeted in the vaults of the cathedral and killed by shelling from what was known as the "Ypres Express", a large calibre German gun firing from the Houthulst Forest. The bodies were not recovered until after the Armistice.

Some 29 non-commissioned ranks of the 6th Battalion DCLI were also killed in action on 12 August 1915:

- Private Frederick Arthur Andrews (11514)

- Private William Albert Charles Ansell (16151)

- Lance Corporal Albert Henry Armer (11850)

- Private Thomas Crowle Arthur (10403)

- Private Silas Bailey (18634)

- Private John Chadwick (12091)

- Corporal Frederick Arnold Chamberlain (10106)

- Private Thomas Collins (17183)

- Lance Corporal Frank Dubbins (10587)

- Sergeant Frank McNevin Duff (16560)

- Private Henry Lewis Duplock (13811)

- Private Henry James Eades (12250)

- Lance Corporal Bernard Jeffery (19643)

- Private David John (10553)

- Lance Corporal William Jones (10537)

- Private William Kay (19349)

- Lance Corporal Richard Lee (11682)

- Private Alfred Albert Lever (18951)

- Private Austin Ley (16888)

- Private Gregory Liddicoat (16668)

- Lance Corporal Herbert Edward May (11847)

- Private Gilbert James Murray (14966)

- Private Leonard Harry Payne (11308)

- Private Daniel Rowe (10468)

- Private (?) George William Scholes (19636)

- Private William John Smith (11798)

- Private William Henry Swain (21109)

- Lance Corporal Howard Taylor (12077)

- Private William Wilton (19781)

After the chaos of the events of 30th and 31st July it was decided that nothing but a carefully worked-out plan would resolve the impasse at Hooge which had existed since the German Offensive at the Second Battle of Ypres. This offensive had made Hooge the vital point of the Ypres Salient as it reached an apex here, and thus it became the focus of attention - or rather more accurately, bitter fighting - as both sides struggled to extract maximum benefit. For the British this meant a tolerable line that could be both defended and supported without excessive casualties; for the Germans it meant domination of the British lines in this sector.

One thing the British attack did achieve on 9th August 1915 and that was the line here remained pretty well static after the battle until it was lost by the Canadians in June 1916.

Extracted from "Sanctuary Wood & Hooge" (1995) Nigel Cave (Leo Cooper, London) at pages 50 to 56

Extract from de Ruvigny's The Roll of Honour 1914-1918 Part 2 Page 58:

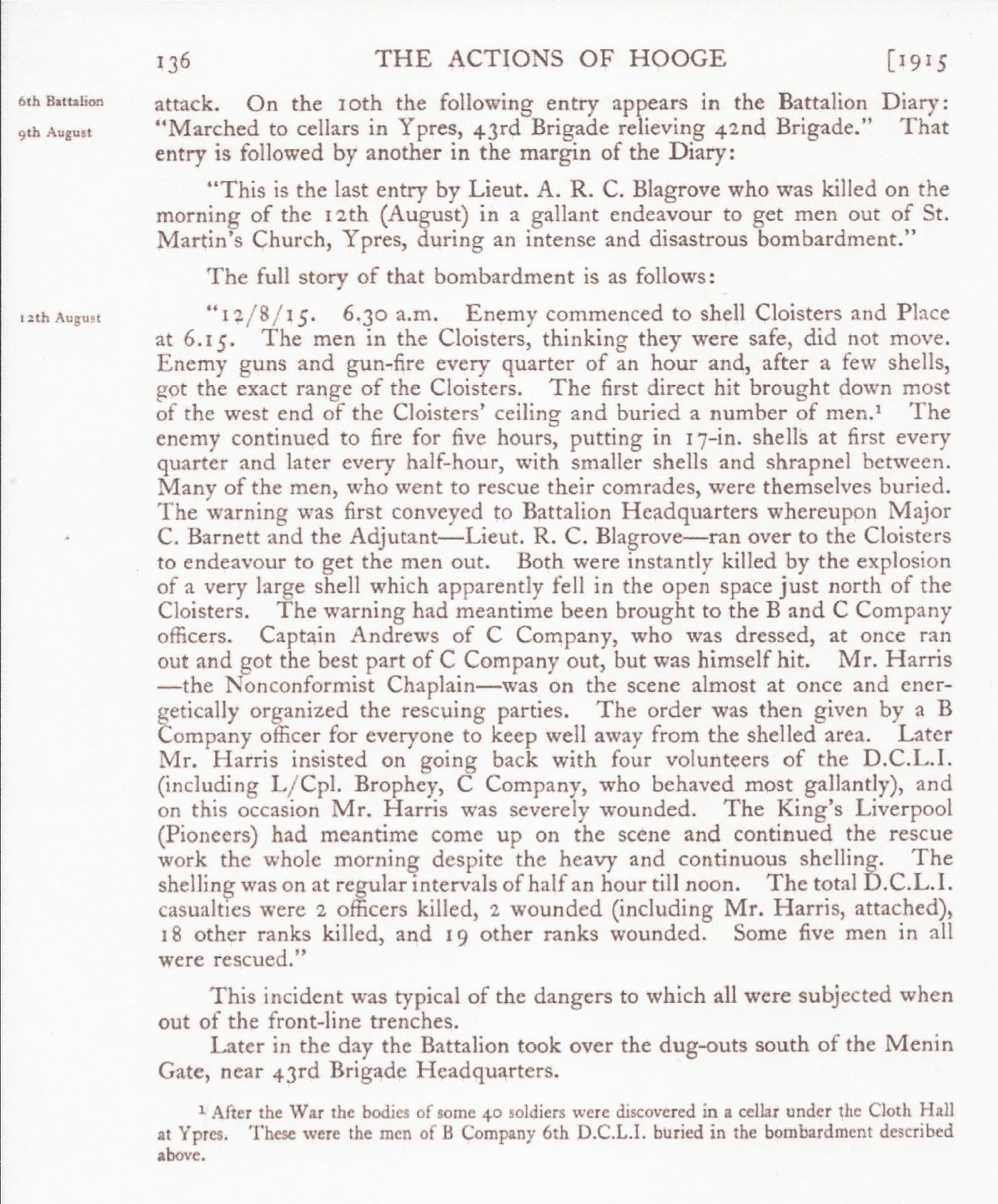

CARMICHAEL, DOUGLAS, Captain, 9th (Service) Battallion, The Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own), eldest son of James Carmichael, of Redclyffe, Streatham Park, London, J.P., by his wife, Annie Reid, daughter of James Reid Ruthvin, of county Perth; born Wandsworth, London, S.W., 17 January 1894; educated Lys School (sic.), Cambridge, and Jesus College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A.; volunteered his services on the outbreak of war, and was gazetted 2nd Lieutenant The Rifle Brigade, 9 September 1914, and promoted Lieutenant 1 October, and Captain 4 March, 1915; went to France in May, and was killed in action at Hooge 26 September following. Lieutenant-Colonel W. Villiers-Stuart wrote on 29 August 1915:

"I am taking the liberty of writing you to tell you about Douglas. From the very beginning he was quite exceptionally valuable, and his capacity and industry were amazing. But he has in the last month been compelled to show himself as he really is - no longer to hide his magnificent qualities under his modest demeanour. The battalion was very badly knocked about in the fighting at … Your son's first act was to collect men of another Regiment, who, by his personality and fearlessness, he rallied and kept with him till long afterwards they were able to rejoin their unit. As time wore on, the incessant bombardment and continued drain in wounded officers began to affect the battalion, and so your son, who had already organized in the most excellent way everything within reach, was sent to steady two companies. Many of the N.C.O.s and riflemen have told me that while your son was near they were perfectly happy. He carried out every kind of duty under incessant shell fire till we were relieved, and I don't think he can have slept at all for many days.

Since then I have had more opportunity than before of seeing his work, and the more I see, the more extraordinarily capable I know (not think) him to be. I have recommended him for some mark of distinction, and he thoroughly deserves such a mark … I would much like you to know that I, an old soldier of many years' service in wild and rough places, would give command of the battalion over to your son today, with the knowledge that he is a better and more capable soldier than any I have seen in twenty-five years' service. His capacity you would know; his coolness is phenomenal, and his bravery quite exceptional."

And again after his death:

"He was killed on 25 September in action near … I saw him last at twelve o'clock midnight, and he was killed next morning about nine o'clock. His bravery is a byword in the division. He fought that day with infinite courage. I have no words, and no one else would have any, to express his magnificent bravery. For long he has done everything for me, and he knew be was absolutely trusted. I shall never see a soldier like him again. It is quite impossible that anyone so fearless could ever be found. He carried four lines of trenches with his company under a most desperate artillery and machine-gun fire, and, when masses of Germans came against him, by his wonderful personality he kept his men, now reduced to a handful, in good spirit, and led them again and again to the attack. They say it was glorious to see him throw himself on the packed masses of Germans and almost alone forced them back. He rallied the men over and over again, and they stuck to him till the end. He was wounded early in the day, about 5 am., but, just like him, made nothing of it. He was killed instantaneously by a bullet in the forehead as he was once more leading a bomb charge. We tried to bring in his body in the evening, but it had been completely destroyed by high-explosive German shells. I will try and tell you better in a few days about it all, but we are so worn out just now that words will not come. He would have earned the V.C. ten times had he lived. He was the most capable and bravest officer of the old army or the new army I have ever or shall ever see, and I can never look on his like again. It is heartrendingly sad that he had to go. Two divisions were attacking. You will know that Douglas carried more German trenches than any other officer on the whole front. Others could not carry any. He at once time carried five lines. If it is possible for you to have any consolation in losing your son, he had become well known for his devotion to duty, bravery and capacity, and I have lost my very best officer and my great friend, who I admired so greatly."

Sergeant W. Walker, Machine Gun Section, also wrote:

"There was not a man in our battalion who would not have followed him anywhere. To cut a long story short, he was in command of the whole attack on the morning of the 25th, and right well did he lead us until he was hit in the leg. Then we pushed forward alone, as he refused to have any assistance; but just after I saw him hopping on one leg towards the next line of German trenches under a murderous fire. We took three lines in all, but had to retire. Your son was still in command, absolutely refusing to be taken back. On reaching the original German front line he rallied the small handful of men left, and told us to hold it at all costs, which we did against masses of Germans until almost every man was either killed or wounded. Your son was killed with a machine gun, and I was twice wounded at the same time. It was instantaneous, and his last words were: 'For God's sake hold them back!'. He earned the V .C. 50 times over. No officer could be loved more or held in higher esteem by his men than your gallant son. A more gallant leader or fearless man never led men on the field of battle." Unm.

Edmund Blunden (1896 to 1974)

| Trench Raid near Hooge | |

|

At an hour before the rosy-fingered Morning should come To wonder again what meant these sties (skies?), These wailing shots, these glaring eyes, These moping mum, |

| Through the black reached strange long rosy fingers All at one aim Protending, and bending: down they swept, Successions of similars after leapt And bore red flame |

|

| To one small ground of the eastern distance, And thunderous touched. East then and west false dawns fan-flashed And shut, and gaped; false thunders clashed. Who stood and watched |

|

|

Caught piercing horror from the desperate pit Which with ten men Was centre of this. The blood burnt, feeling The fierce truth there and the last appealing, "Us? Us? Again?" |

| Nor rosy dawn at last appearing Through the icy shade Might mark without trembling the new deforming Of earth that had seemed past further storming. Her fingers played, |

|

| One thought, with something of human pity On six or seven Whose looks were hard to understand, But that they ceased to care what hand Lit earth and heaven. |

|

| Edmund Blunden's notebook for poetry in the trenches | Poetica, Vol. [1], No 3, April 1925 Undertones of War, November 1928 (revised) |

Edmund Blunden's poem 'Trench Raid Near Hooge' visualises false untimely "rosy-fingered" dawns with false thunders which are, in reality, caused by deadly gunfire, bombs, shells and the "long rosy fingers" of the German flammenwerfer.

The Riddle of the Rhine Chemical Strategy in Peace and War

Being an "account of the critical struggle for power and for the decisive war initiative. The campaign fostered by the great Rhine factories, and the pressing problems which they represent. A matter of pre-eminent public interest concerning the sincerity of disarmament, the future of warfare, and the stability of peace" written by Victor Lefebure and first published in 1923. The following is an extract from a section headed "The Flammenwerfer":

The Flammenwerfer

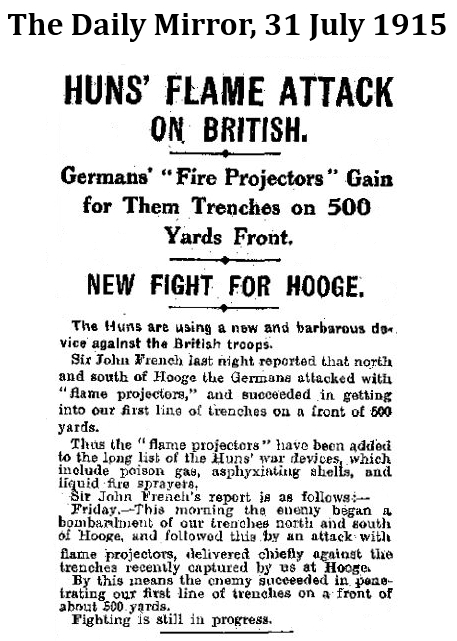

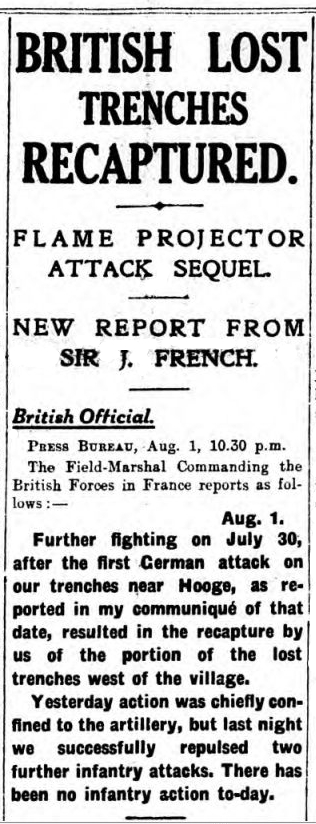

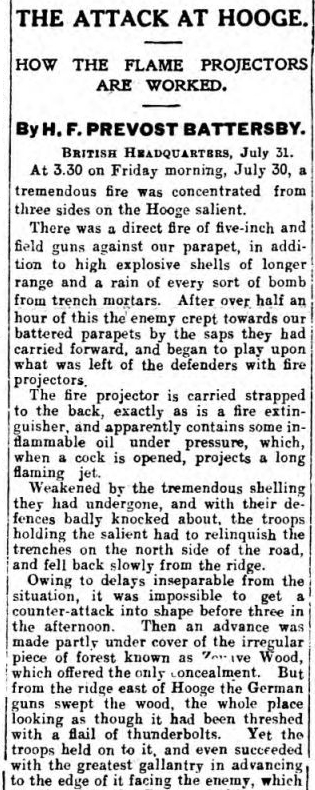

There can be no doubt that this period marks increasing German willingness to live up to their "blood and iron" theories of war, and, in July 1915, another device with a considerable surprise value was used against us: the flame projector, or the German flammenwerfer. Field-Marshal Sir John French signalled the entry of this new weapon as follows:

"Since my last despatch a new device has been adopted by the enemy for driving burning liquid into our trenches with a strong jet. Thus supported, an attack was made on the trenches of the Second Army at Hooge, on the Menin Road, early on 30th July. Most of the infantry occupying these trenches were driven back, but their retirement was due far more to the surprise and temporary confusion caused by the burning liquid than to the actual damage inflicted. Gallant endeavours were made by repeated counter-attacks to recapture the lost section of trenches. These, however, proving unsuccessful and costly, a new line of trenches was consolidated a short distance farther back."

Although this weapon continued to be used right through the campaign, it did not exert that influence which first acquaintance with it might have led one to conclude. At the same time, there exists a mistaken notion that the flame projector was a negligible quantity. This may be fairly true of the huge non-portable types, but it is certainly not true of the very efficient portable flame projector which was the form officially adopted by the German, and later by the French, armies. On a number of occasions Germany gained local successes purely owing to the momentary surprise effect of the flame projector, and the French made some use of it for clearing out captured trench systems over which successful waves of assault had passed. Further, the idea of flame projection is not without certain possibilities for war.

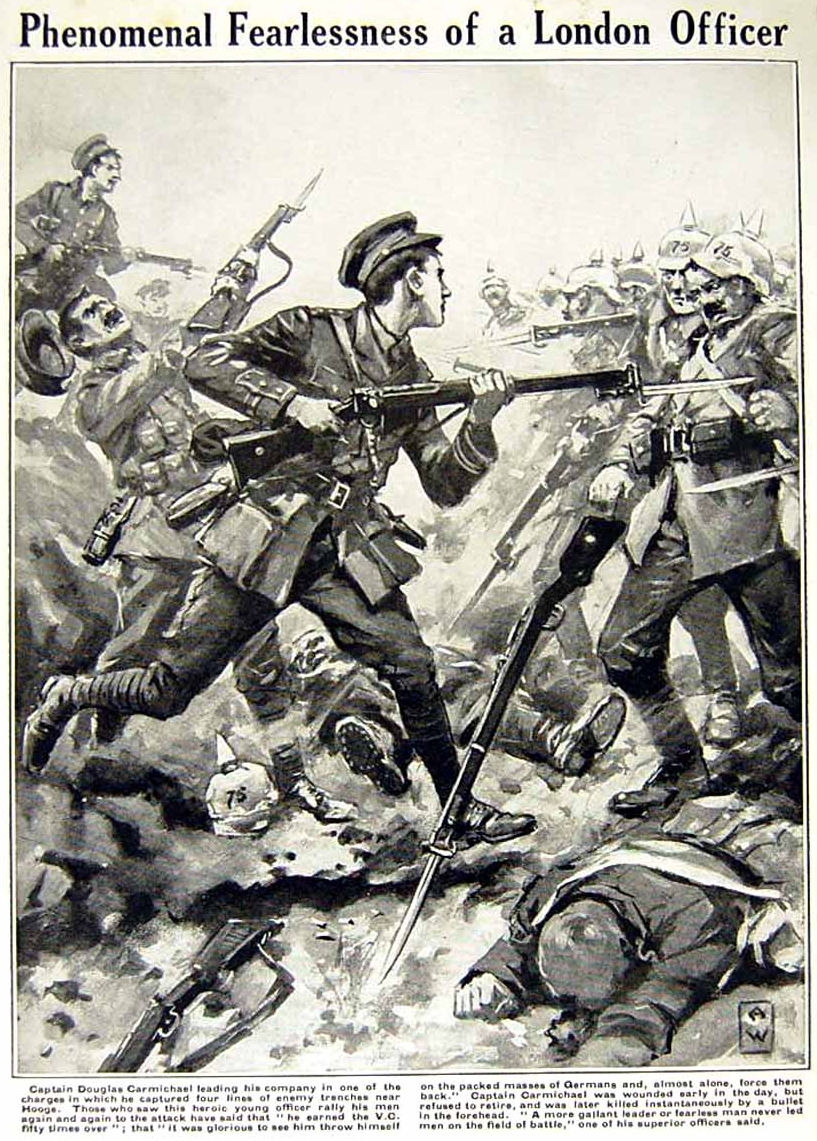

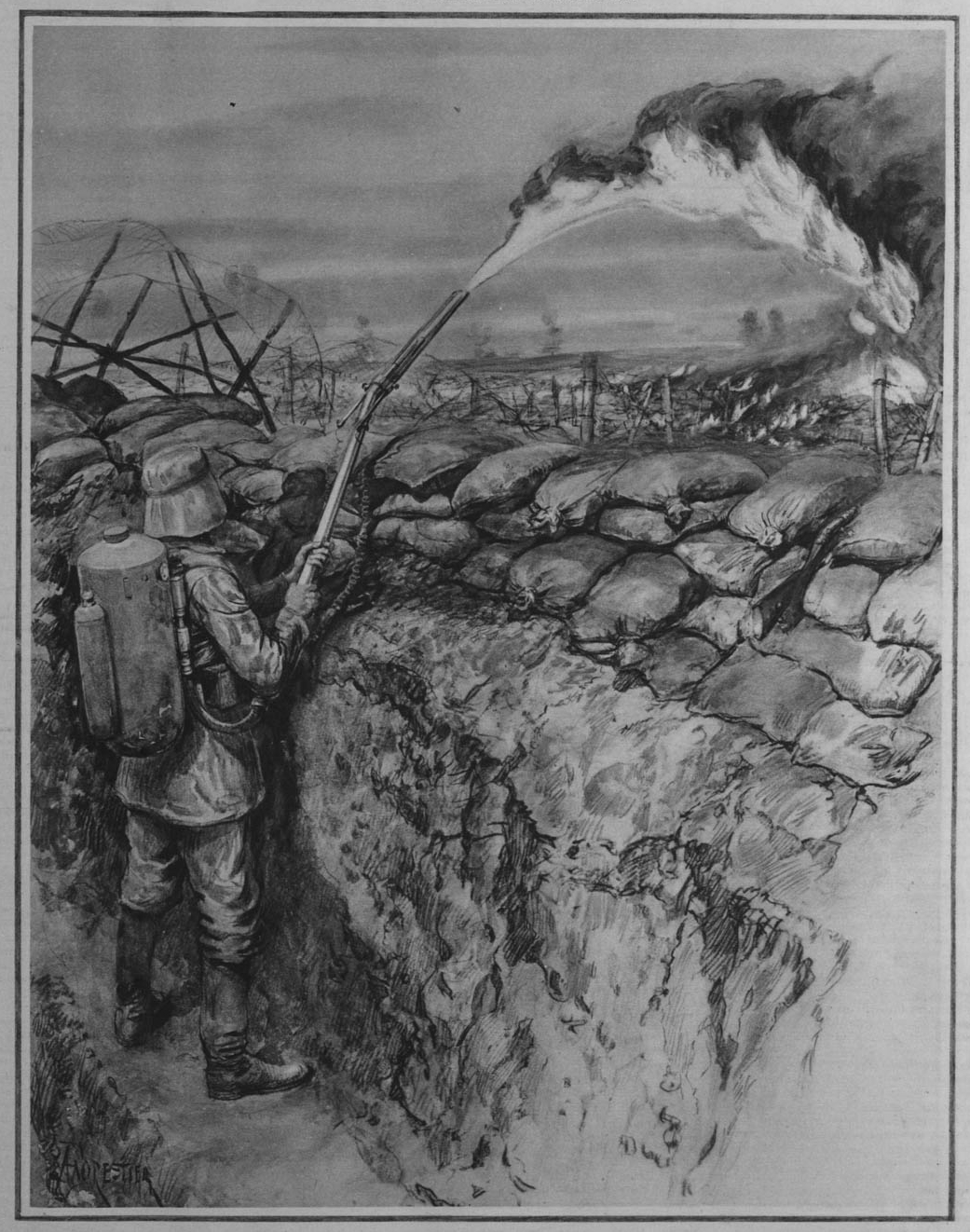

The Illustrated London News, Saturday 21 August 1915

Spraying Liquid Fire: The German "Flammenwerfer" in Action

How the enemy took some British trenches (since recaptured) at Hooge: A flame-projector, one of the diabolical instruments invented by German chemical science, in use by a German soldier.

In a recent despatch Sir John French said:

"The enemy began a bombardment of our trenches north and south of Hooge, and followed this by an attack with 'flame-projectors'. By this means the enemy penetrated our first line of trenches on a front of about 500 yards".

Later, Sir John was able to announce the recapture of these trenches.

Our artist has illustrated (from a source which we are not at liberty to mention, but which is absolutely reliable) one of these diabolical flame-projectors, or Flammenwerfer, and the German method of using it.

We are informed that the apparatus consists of a reservoir, containing petrol mixed with a small proportion of kerosene (to give body to the liquid), and attached thereto are a cylinder of highly compressed air, a pressure-gauge, a starting-valve and an electric battery with induction-coil. Connected to the reservoir by a flexible coupling is a long spraying-tube, which may be pointed to any angle. To the end of the tube are attached two rods which terminate in an electrical spark gap, so that, when the main valve is opened, the liquid is forced out by great air-pressure and is ignited by the spark. Frequently the liquid is directed on to the Allies' trenches in its raw state, and is afterwards ignited by the burning stream. The effective range of a flame-projector is about thirty yards.

Hooge Crater Museum

|

| Hooge Crater Museum, Ypres, Belgium |

| Museum Hooge Crater, Meenseweg 467, B-8902 Zillebeke-Ieper, Belgium |

| The Hooge Crater Museum is situated just in front of the Hooge Crater Cemetery, about a half mile from the Bellewaerde theme park along the Menin Road (N8) |

| Telephone +32 (0)57 46 84 46 |

| Fax +32 (0)57 46 87 12 |

| email: info@hoogecrater.com |

| Open daily 10 am to 6 pm (closed Monday) and 10 am to 9pm Sunday from 28 January to 22 December (closed 12 to 19 August). Outside these hours open only for groups (minimum 20 persons) by prior reservation |

| Admission charges are €4.50 (adult) and €2 (child). The group rate for adults is €3 (each) and for students €2 (each) |

| There is a café and toilets. Books and postcards are for sale. |

A privately owned museum containing a very good collection of First World War uniforms, displays and artefacts. Besides the traditional pictures, weapons and equipment this new museum shows reconstructions of war scenes with life-size horses and soldiers in the uniforms of the involved nations. Location: leave Ypres via its eastern gate (Menin Gate). At the traffic lights turn right onto the Ieper-Menen road (Menin Road). The museum is located approximately 4 kilometres east of Ypres on the north side of the Menin Road in the converted Hooge chapel.

Frontline Hooge Museum

During 1915 the fighting around Hooge was brutal. There was constant fighting for the remains of the Chateau and its stables. Mine warfare was also an early feature here and the 3,500 pound mine detonated on 19th July 1915 was, for a time, the largest on the western front. The German army counter-attacked on 30th July using, for the first time, liquid fire. "Armageddon Road: A VC's Diary" by Billy Congreve VC describes this battle. His father, General Walter Congreve VC, wrote about Hooge:

"Everywhere dead men, some days old and some blown to bits. You step over them in the trenches and see them wherever you look out of the trenches."

Billy had been up at Hooge on many occasions but after the successful German attack he wrote in his diary that he was glad his father was up at Hooge and not he.

After the war a new chateau was built on the site of the former stables. In later years this chateau became a hotel. In the grounds of this hotel the remains of the fighting can be seen including the famous Hooge crater (full of water) and British and German concrete bunkers. In 1997 the Frontline Hooge (entrance charge £1.50) - not to be mistaken with the Hooge Crater Museum - was set up in the grounds, part of which is an archaeological excavation of a World War One trench, the guide to which reads as follows:

You are now looking at the only First World War trench ever to be the subject of an archaeological excavation. Please do not cross the yellow tape, the excavation is still progressing. This section of the trench has been restored to its original condition. Note the following features:

The Fire-step - This is the step upon which the soldiers would stand to look over the parapet towards the German lines. If necessary they would fire through the spaces in the sandbags.

The Dugout - For most of the troops in the frontline there was absolutely no shelter from the appalling weather. They would huddle under a waterproof cape whilst sitting on the fire-step. If they were more fortunate then they would squeeze into a dugout such as the one you see before you.

You will notice that the trench was built to a zig-zag plan. This offered a greater protection against exploding shells. A trench comprising of a simple straight line would be vulnerable to firing along its length if any enemy soldier managed to enter a part of it.

As you look down into the trench you will see the original wooden walkways (duckboards) still in their original position. There is a communication wire running down one side of the trench. It was by following these duckboards that the line of the trench was determined during the excavation. These duckboards have been left in position to prove the authenticity of the trench.

This frontline trench was initially built by the Germans in early 1915 and was captured by British troops on 19 July the same year as the Germans were pushed back 50 metres after the first mine was detonated. Eleven days later at 3.15am on 30 July the Germans regained the position with the help of flame-throwers, their new 'terror weapons'. This was the first time that British troops had ever faced flame-throwers and in the chaos and the darkness they were driven back to just over the Menin Road.

Ten days later the tide of battle turned yet again and the trench was retaken by the British with the Germans then digging in where the waterslide now stands. It was in this attack that steel helmets were first used.

After preparing for 6 weeks an attempt was made by the British to capture the German trenches. Early in the morning of 25 September thousands of men went 'over the top' from this trench and others to either side of it. The attack failed and 4,000 men were lost. After months of deadlocked trench warfare the situation suddenly changed in June 1916 when the trench was lost to a sudden German offensive. It remained in German hands until 31 July 1917. As the British successfully pushed the Germans eastwards Hooge became relatively quiet for a few months with only the occasional shell smacking into the sodden soil. Suddenly, in the spring of 1918 the Germans were back, smashing through the British lines and fighting their way through Hooge to be stopped only at the very gates of Ypres. Finally, on 28 September 1918 Hooge shook to the sounds of battle yet again as the Germans retreated for the last time. Tens of thousands of men had died here by the time the war ended. Today, as you look about you it is difficult to imagine a more peaceful scene. Yet beneath the soil lie the bodies of hundreds of soldiers of both sides who fell in the battles of 80 years ago and whose graves are 'known unto God'.

|

|

|

The Daily Express, Monday 2 August at page 1 |

||

|

|

|