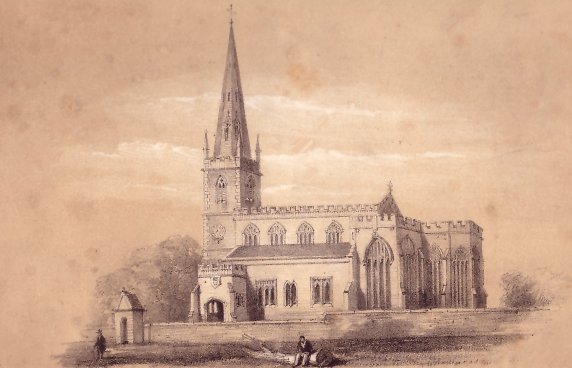

St Bartholomew's Church, Wednesbury (before 1827)

St Bartholomew's Church, Wednesbury, Interior (before 1827)

Samuel RAMSDALE was baptised on Tuesday, 12 December 1721 in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire. On Wednesday, 24 April 1751 Samuel RAMSDALE married Hannah BAGLEY at Saint Bartholomew, Wednesbury, Staffordshire.

Hannah RAMSDALE (née BAGLEY) is believed to have been buried on Sunday, 12 July 1795 in St John Baptist Church, Bromsgrove, Worcestershire. However, another entry in the register of this church records a burial on Sunday, 1 February 1801 for Hannah RAMSDALE described as the "wife of Samuel, pauper, buried in St John Baptist Church, Bromsgrove."

Children

- Sarah RAMSDALE, baptised in Saint Bartholomew, Wednesbury, Staffordshire on Monday, 1 March 1752

- Joseph RAMSDALE, baptised in Saint Bartholomew, Wednesbury, Staffordshire on Sunday, 16 December 1753. On Sunday, 27 October 1771 Joseph RAMSDALE married Anne ROWLASTON in Saint Bartholomew, Wednesbury.

- Edward RAMSDALE, baptised in Saint Bartholomew, Wednesbury, Staffordshire on Sunday, 25 January 1756, married Hannah ROSS (baptised on Sunday, 13 November 1757 in Saint Bartholomew, the daughter of John ROSS and Sarah STEVENSON (baptised on Friday, 24 February 1721) who were married in Saint Bartholomew on Sunday, 11 August 1751) in Saint Bartholomew on Saturday, 14 June 1777. Edward RAMSDALE is believed to have died in Staffordshire in 1835.

Wednesbury is one of the oldest parts of Sandwell. The "bury" part of the name indicates there may have been an Iron Age fort or "beorg" on Church Hill as long ago as 200BC, and the town was certainly a key defensive feature of the kingdom of Mercia.

In the Middle Ages the town was a rural village, with each family farming a strip of land and the heath nearby used for grazing. It was held by the King until the reign of Henry II, when it passed to the Heronville family. In the 14th century, while Wednesbury was still a farming community, local people began to mine their own coal and iron. By Tudor times, when local landowner William Paget was one of the most prominent men of the kingdom, pottery, metalwork and textiles were made. In the 17th century Wednesbury pottery - "Wedgbury ware" - was being sold as far afield as Worcester, while white clay from Monway Field was used to make tobacco pipes.

In the 18th century the town's main occupations were coal mining and nail making and with the canals came a big increase in population. The poor social conditions proved a fertile breeding ground for religious nonconformism, and in 1743 John Wesley first preached in the town. His views were not always well received - fears that he was trying to undermine society led to riots, and on one occasion he was chased out of the area.

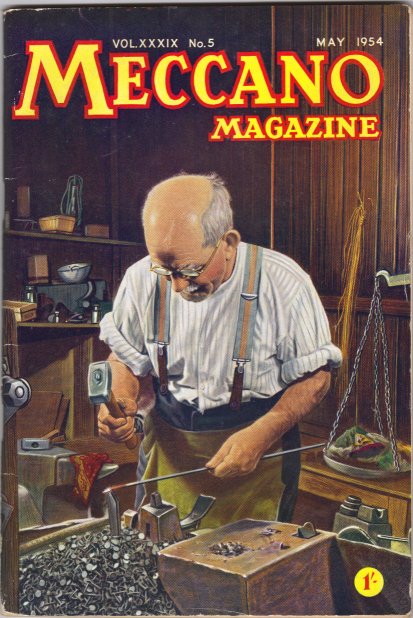

Mr Albert Crane, one of the last Worcestershire nailmakers, in 1951

Hand-Made Nails, Meccano Magazine, Volume XXXIX No 5, May 1954 by W. K. V. Gale

The making of nails by hand was a very old craft. References to nails made in Staffordshire, which eventually became the great centre of the trade, were made as early as the reign of King John, from 1199 to 1216. The trade was always domestic in character, the work being carried on in little workshops attached to the nailers' dwelling houses.

Over a long period nailing expanded, and from about 1750 onwards, when improved iron-making techniques made available increased quantities of iron rods suitable for nail making, the expansion was considerable. By about 1830, no less than 50,000 workers were engaged in nailing in south Staffordshire and north Worcestershire. The trade had then reached its peak.

Machine-made nails had been introduced some years earlier, and the machine competed with the hand worker with increasing success from that time onward. The result was a steady decline in the number of nailers at work. By 1900 only about 4,300 nailers remained, and in the following 50 years the trade became virtually extinct. A few nailers were still to be found in Worcestershire in 1951, and one of these survivors (Mr Albert Crane) of a once-great trade is shown at work above.

Like many other old trades, nail making had its own customs, some of them unique. Nailing was essentially a family enterprise, even the children being put to work as soon as they were big enough to be of use. Starting at a very early age, the nailer soon developed a high degree of skill, and it is of interest to note that a careful study of a nailer at work in 1951 showed that there was no possible means of improving his technique. By long practice he had become so fast and skilful at his work that only the machine could beat him.

The nailer's equipment was simple. He had a hand hammer, a small anvil, a "bore" or hollow tool in which the partly-finished nail was placed to have its head formed, and a treadle-hammer for heading. The iron rods were heated in a small hearth similar to that used by a black-smith, but much smaller. Some idea of the skill developed by long practice can be gained from the fact that the nailer shown above (Mr Albert Crane) made two brush nails, which are like large tacks, every six seconds. They were surprisingly uniform in size and shape, the more so as the nailer had no means of measuring, and judged the amount of iron on which he worked solely by eye.

The business of marketing the nails was very complex. It was undertaken by a nail master, who supplied the iron to the nailer, and bought his finished nails. The basis of trading was the "tale" or thousand nails but that was purely nominal, since the nailer had to deliver to the master 1,200 nails for every nominal thousand, while the master, in selling, used a count of 960 or 750 per thousand.