DRR DNA

Paternal Ancestry

DNA Test Results

- familytreedna.com Big Y-700 results published 3 August 2020

- ancestry.com

- myheritagedna.com

- 23andme.com

- livingdna.com DNA test results awaited (2 May 2020)

- crigenetics.com DNA test results awaited (2 May 2020)

- Genetic Ancestry Testing (articles)

- Maternal ancestry

1. familytreedna.com DNA Test Results

| Product | Completed |

|---|---|

| mtFull Sequence | 26 May 2010 |

| Y-DNA67 | 30 March 2010 |

| Deep Clade-R | 27 May 2010 |

| L165 | 6 July 2011 |

| L176.2 | 6 July 2011 |

| DF19 | 4 October 2011 |

| Z196 | 18 July 2011 |

| L238 | 18 July 2011 |

| Big Y Raw Data | 9 December 2015 |

| Big Y-500 | 19 April 2018 |

| Y-DNA111 | 27 January 2016 |

| Family Finder | 18 January 2016 |

| DF27 | 13 May 2016 |

| R1b - DF27 SNP Pack | 19 August 2016 |

| Big Y-700 | 3 August 2020 |

The 'Big Y' is a familytreedna Y-chromosome direct paternal line test:

- designed to explore deep ancestral links on our common paternal tree by examining thousands of known branch markers as well as millions of places where there may be new branch markers;

- intended for expert users with an interest in advancing science;

- which may also be of great interest to genealogy researchers of a specific lineage.

However, it is not a test for matching one or more men with the same surname in the way that other familytreedna Y-STR tests do, such as Y-37, Y-67 or Y-111.

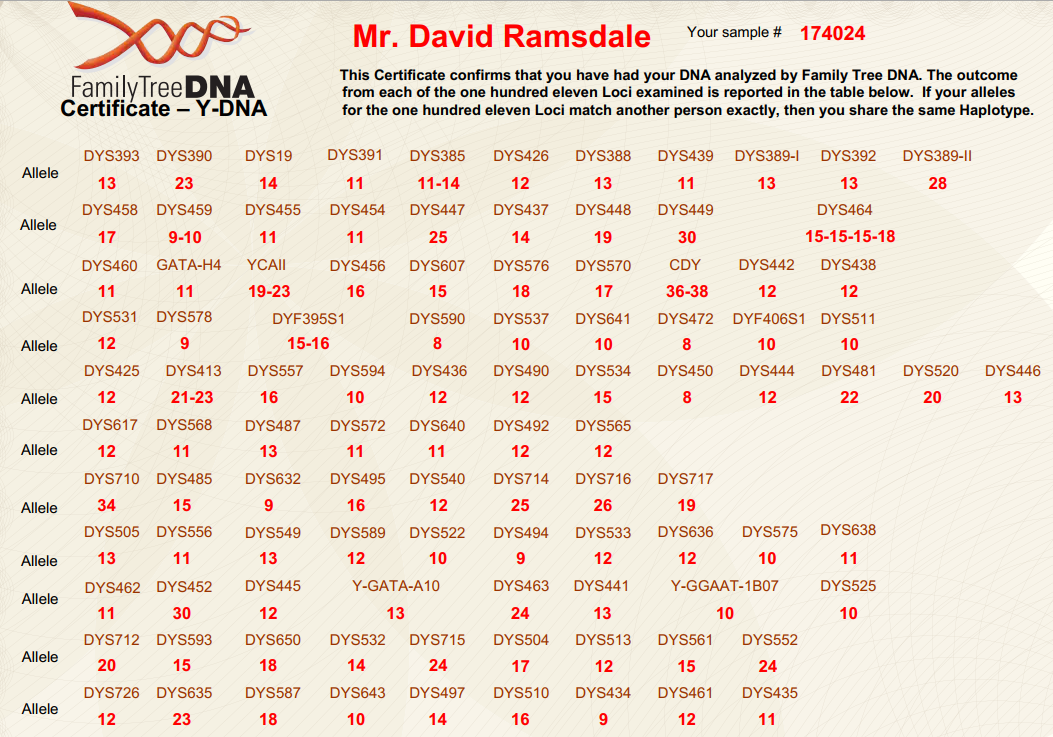

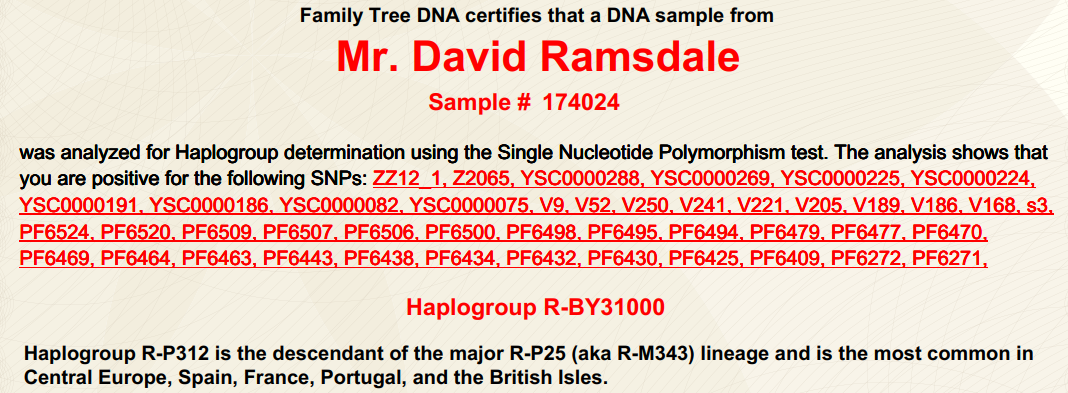

| DRR confirmed Haplogroup is R-FT31031 (formerly R-ZZ12_1, R1b1a2a1a1b* and R-BY31000) |  |

Haplogroup R-P312 is the descendant of the major R-P25 (aka R-M343) lineage and is the most common in Central Europe, Spain, France, Portugal, and the British Isles. |

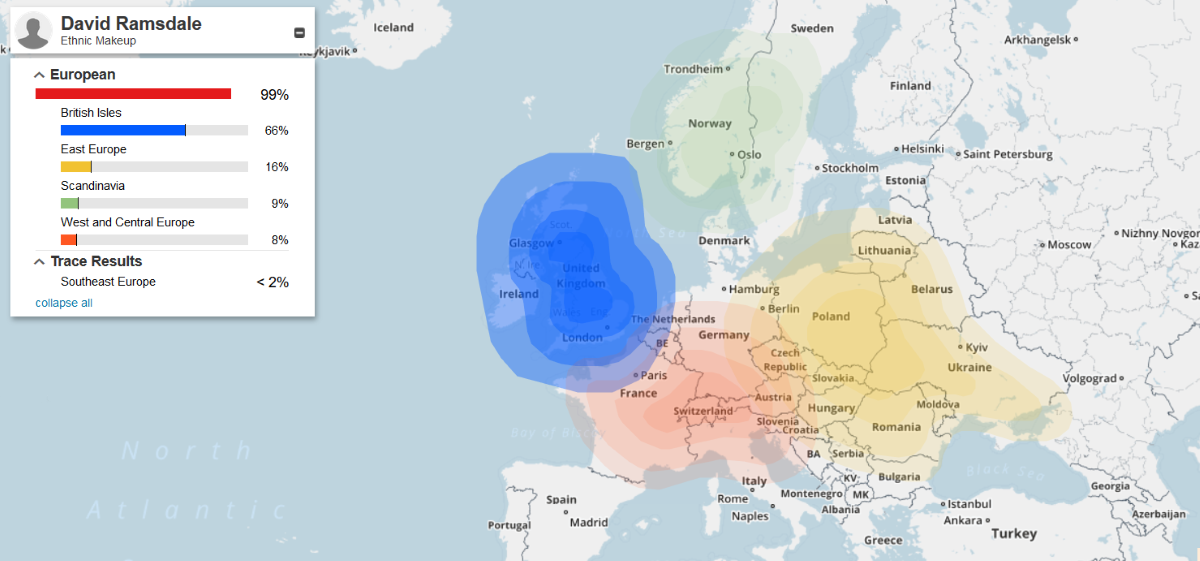

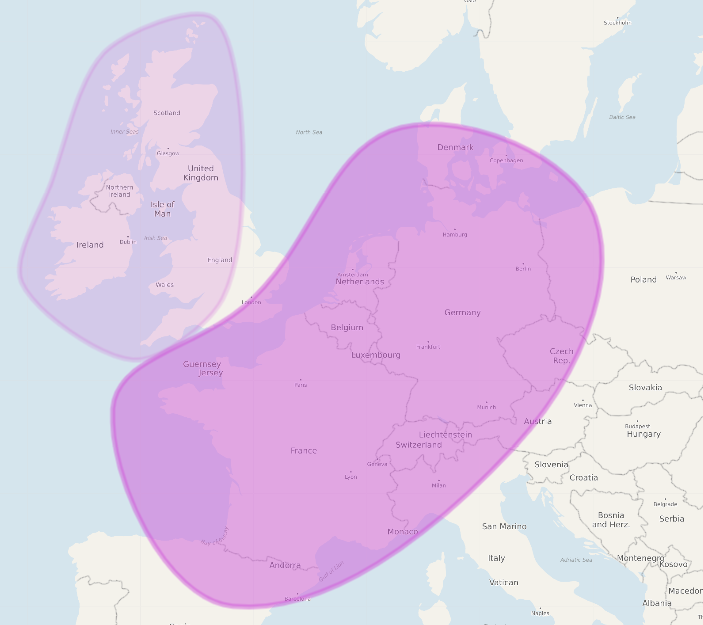

(above) DRR Ethnicity (familytreedna.com)

(above) DRR Y-DNA 12 marker matches: 33 (familytreedna.com)

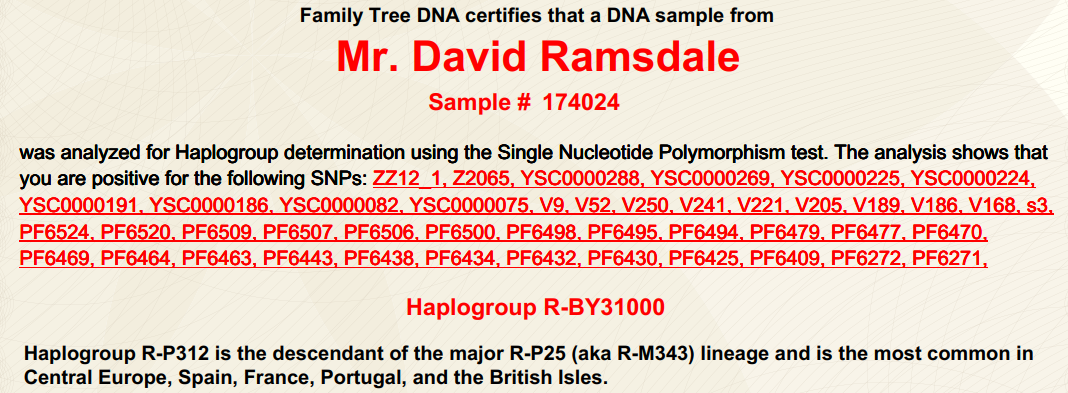

(above) Push pin match colours (familytreedna.com)

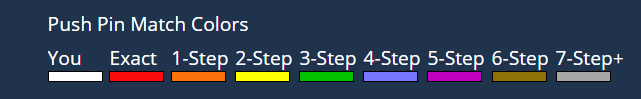

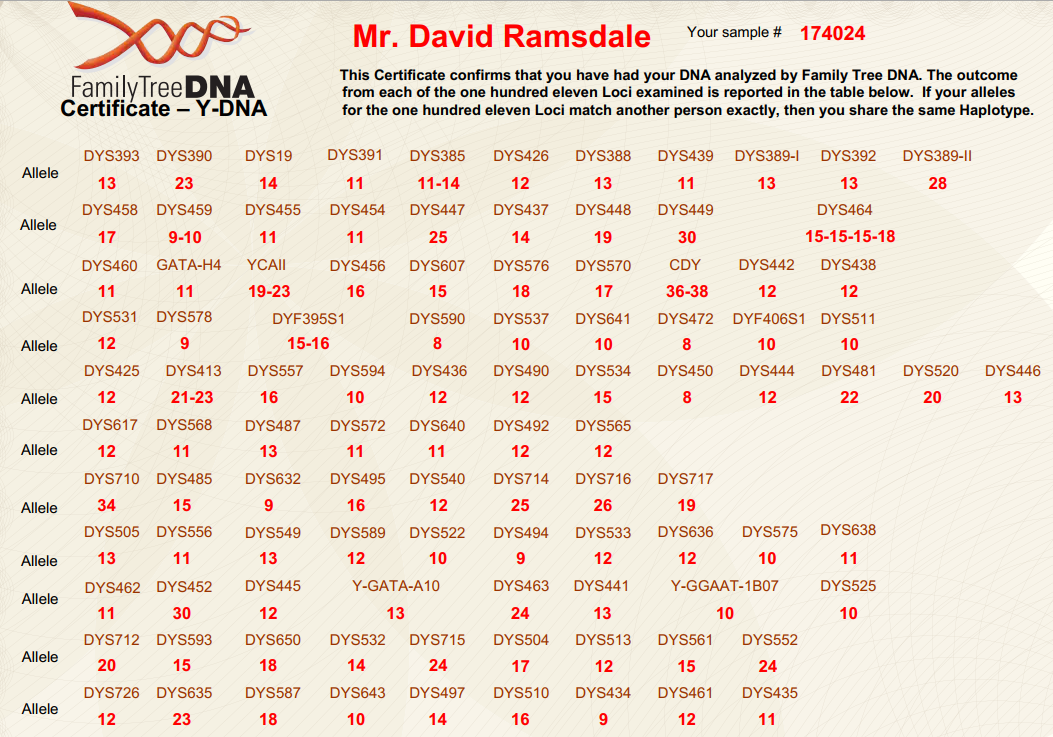

(above) DRR Y-DNA

(above) DRR DNA Haplogroup

(above) DRR Y-DNA

(above) DRR DNA Haplogroup

| SNP Tests Taken | ||

|---|---|---|

| SNP Name | Positive | Test |

| L21 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| L48 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| M153 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| M269 | True | Deep Clade-R |

| M65 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| P312 | True | Deep Clade-R |

| SRY2627 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| U106 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| U152 | False | Deep Clade-R |

| L165 | False | L165 |

| L176 | False | L176.2 |

| DF19 | False | DF19 |

| Z196 | False | Z196 |

| L238 | False | L238 |

| BY11750 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY12045 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY22302 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY27761 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY3070 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31000 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31001 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31002 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31003 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31004 | True | Big Y-500 |

| BY31005 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS10834 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS11985 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS12478 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS2664 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS3063 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS3358 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS3575 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS3654 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS4244 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS4368 | True | Big Y-500 |

| CTS623 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F115 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1209 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1329 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1704 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1714 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1753 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F1767 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2048 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2142 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2155 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2402 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2587 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2688 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2837 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F2985 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F3111 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F313 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F3136 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F3335 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F3556 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F3692 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F47 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F719 | True | Big Y-500 |

| F82 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L1090 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L11 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L132 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L136 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L15 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L150 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L16 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L23 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L265 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L278 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L350 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L388 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L389 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L407 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L468 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L470 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L478 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L482 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L483 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L498 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L500 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L502 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L506 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L51 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L52 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L585 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L747 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L752 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L754 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L761 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L768 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L773 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L779 | True | Big Y-500 |

| L82 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M168 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M173 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M207 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M213 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M235 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M269 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M294 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M299 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M306 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M343 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M415 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M42 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M45 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M526 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M74 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M89 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M9 | True | Big Y-500 |

| M94 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P128 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P131 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P132 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P133 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P134 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P135 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P136 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P138 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P139 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P14 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P140 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P141 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P143 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P145 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P146 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P148 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P149 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P151 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P157 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P158 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P159 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P160 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P161 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P163 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P166 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P187 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P207 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P224 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P225 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P226 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P228 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P229 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P230 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P231 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P232 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P233 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P234 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P235 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P236 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P237 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P238 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P239 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P242 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P243 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P244 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P245 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P280 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P281 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P282 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P283 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P284 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P285 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P286 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P294 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P295 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P297 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P310 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P311 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P312 | True | Big Y-500 |

| P316 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PAGES00026 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PAGES00081 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PAGES00083 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2591 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2608 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2611 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2615 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2643 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2745 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2747 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2748 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2749 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF2770 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF3561 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5471 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5869 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5871 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5882 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5886 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5888 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5953 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5956 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5957 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5964 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5965 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF5982 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6246 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6249 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6250 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6263 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6265 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6270 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6271 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6272 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6409 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6425 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6430 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6432 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6434 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6438 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6443 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6463 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6464 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6469 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6470 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6477 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6479 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6494 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6495 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6498 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6500 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6506 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6507 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6509 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6520 | True | Big Y-500 |

| PF6524 | True | Big Y-500 |

| s3 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V168 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V186 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V189 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V205 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V221 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V241 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V250 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V52 | True | Big Y-500 |

| V9 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000075 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000082 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000186 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000191 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000224 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000225 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000269 | True | Big Y-500 |

| YSC0000288 | True | Big Y-500 |

| Z2065 | True | Big Y-500 |

| DF27 | True | DF27 |

| A2145 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A2146 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A431 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A432 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A433 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A434 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A4658 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A4659 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A4670 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A6456 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A6458 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A7014 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A7380 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| A7385 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY2285 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3232 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3233 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3235 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3286 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3287 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3288 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3289 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3290 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3291 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3292 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3327 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3328 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3329 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3330 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3331 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY3332 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY653 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| BY834 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS1090 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS11567 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS1643 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS416 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS5885 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS6578 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS7768 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| CTS9952 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF17 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF27 | True | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF79 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF81 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF83 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| DF84 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC11369 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC11414 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC11419 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC13109 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC13110 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC13125 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14113 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14114 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14115 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14124 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14126 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14934 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC14951 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC17099 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC17102 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC17112 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC17114 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20556 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20747 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20748 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20755 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20761 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20764 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20767 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC20816 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC21115 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC21124 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC21129 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC23066 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC23071 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC23074 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC23079 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC23083 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC30918 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC30962 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC30964 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC30993 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC30994 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC31068 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| FGC8127 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| L617 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| L881 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| M225 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| M756 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| P312 | True | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| PH133 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| PH2047 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| S1041 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| S400 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| S7432 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| SK2109 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y13115 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y14084 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y14468 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y14469 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y15636 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y15637 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y15639 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y15924 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y15926 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y16018 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y16863 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y17221 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y17446 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y17787 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y4865 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y4867 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y5058 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y5072 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y5077 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y6949 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y6951 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y7363 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Y7364 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| YP4295 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z1513 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z1899 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z195 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z196 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z198 | No call or heterozygous call | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z209 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z20907 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z220 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z223 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z225 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z226 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z229 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2543 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2545 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2547 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2556 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2560 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2563 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2564 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2566 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2567 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2571 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z2573 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z268 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z274 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z296 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z29614 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z29624 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z29875 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z29878 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z29884 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z32156 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z32164 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z34609 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| Z37492 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| ZZ12_1 | True | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| ZZ12_2 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| ZZ19_1 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

| ZZ20_1 | False | R1b - DF27 SNP Pack |

2. ancestry.com DNA Test Results

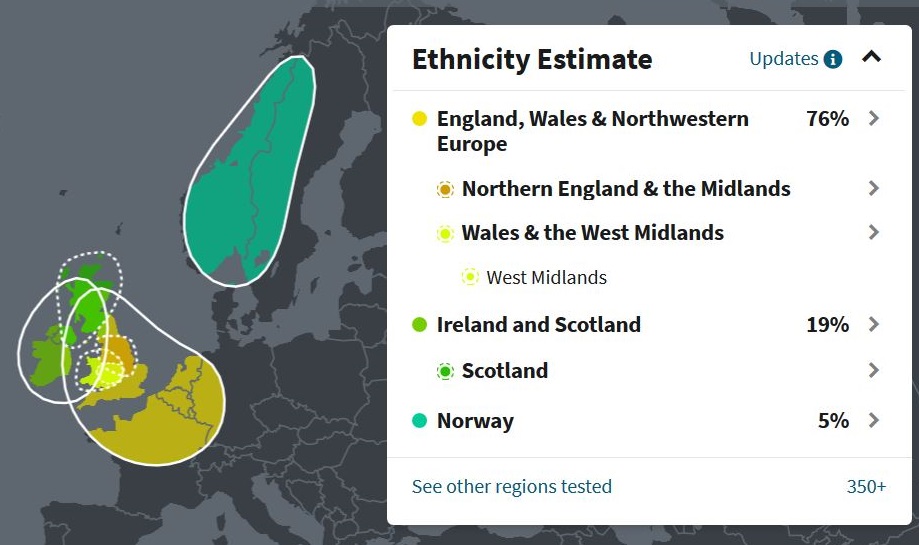

(above) DRR Ethnicity Estimate (ancestry.com)

| Ethnicity Estimate: Original and Updated (ancestry.com) | ||

| Region | Original (September 2018) |

Updated (August 2019) |

|---|---|---|

| England [1], Wales and Northwestern Europe | 76% | 89% but possibly 84>100% |

| Ireland and Scotland | 19% | 5% but possibly 0>8% |

| Norway (and Iceland) | 5% | 3% but possibly 0>10% |

| Sweden | 0% | 3% but possibly 0>3% |

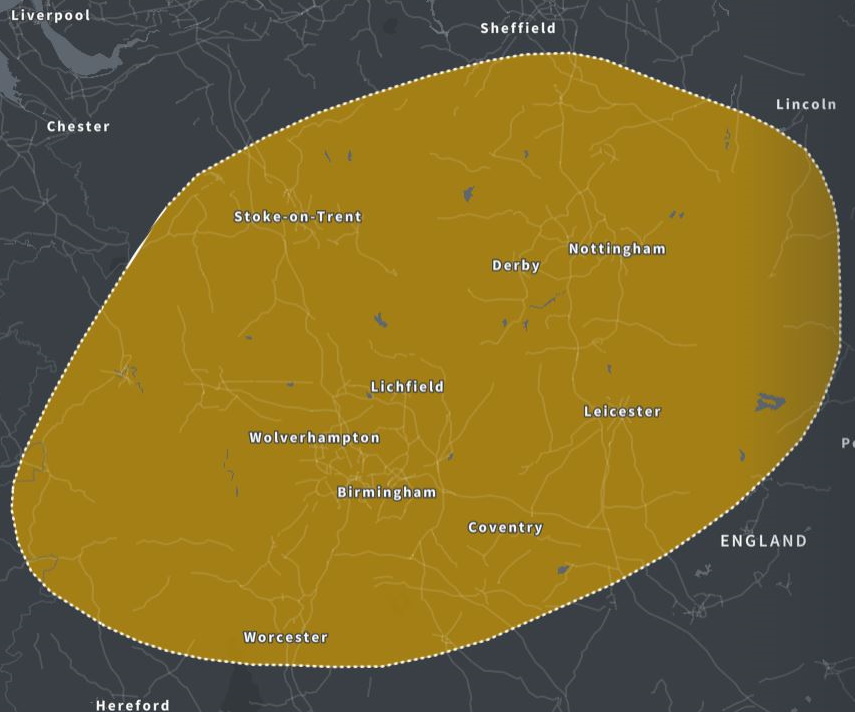

| [1] The Midlands, England. Members of this community are linked through shared ancestors and probably have family who lived in this area for years. | ||

(above) The Midlands (ancestry.com)

| Your DNA doesn't change, but our science does. Don't worry, your DNA doesn't change. What changes is what we know about DNA, the amount of data we have, and the ways we can analyze it. When that leads to new discoveries, we update your results. |

| How is my estimate calculated ? To calculate your estimate, we compare your DNA to a reference panel of DNA from around the world. As we get more samples in our panel, we can identify more world populations for you. |

| How might my estimate change ? You might see new regions, old regions replaced or split into new ones, changes in percentages, or just minor refinements. These changes could be large or small depending on what we're updating. |

| How do updates improve my result ? Updates take advantage of new technology, science, and data to make your results even more precise. Think of it as an upgrade to the latest model |

| How could one of my percentages change so much ? We've split some regions into smaller regions. We also have better ways of telling some neighbouring regions apart. Either could mean large changes to your percentages. |

| Why does the map look different ? Changes to the ethnicity map reflect data from our updated reference panel and refinements in how we show that data. Now, the shapes and shading on the map better represent our data for each ethnicity region. |

(above) DRR Ethnicity Estimate Updated August 2019 (ancestry.com)

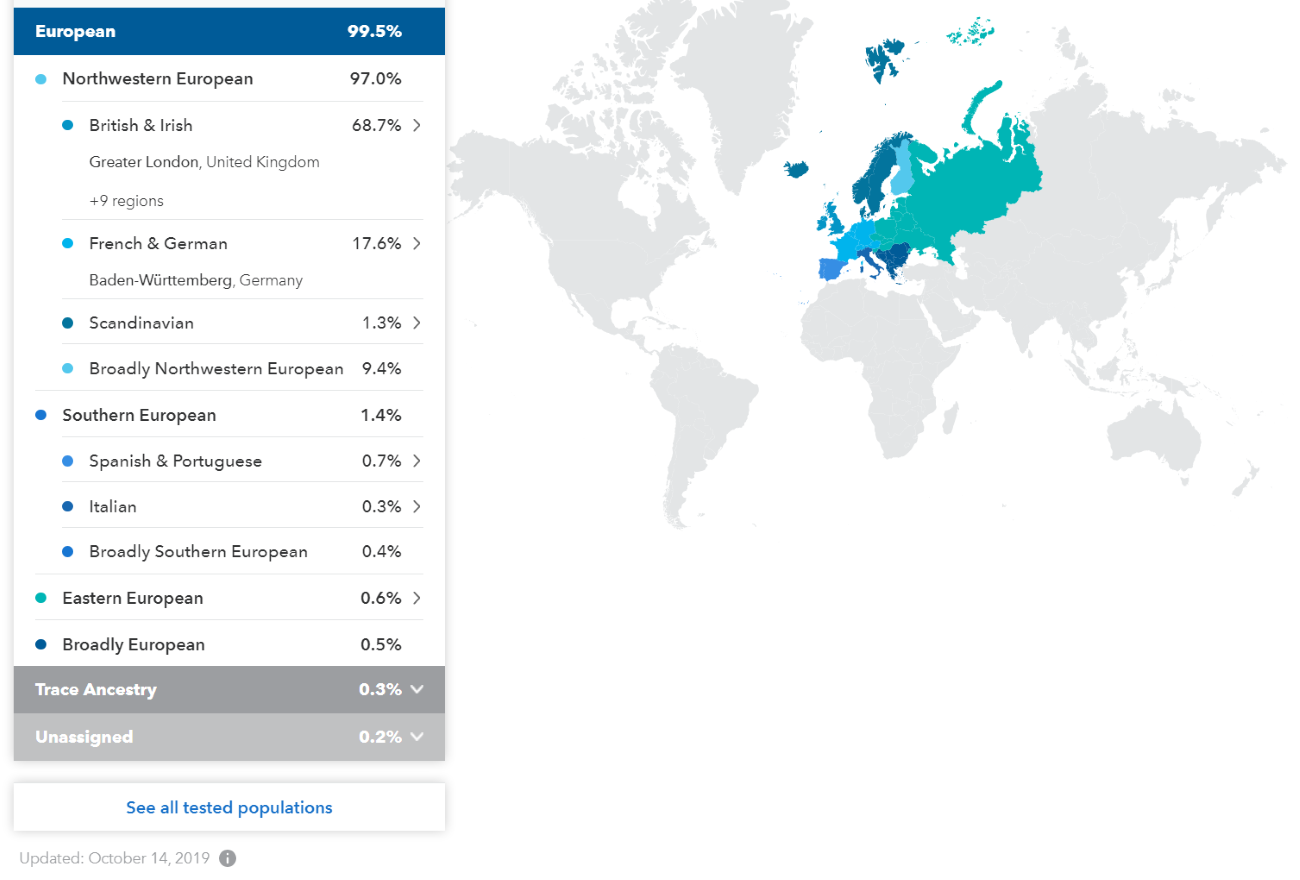

3. myheritagedna.com DNA Test Results

|

|

| (above) DRR Ethnicity (myheritagedna.com) | |

4. 23andme.com DNA Test Results

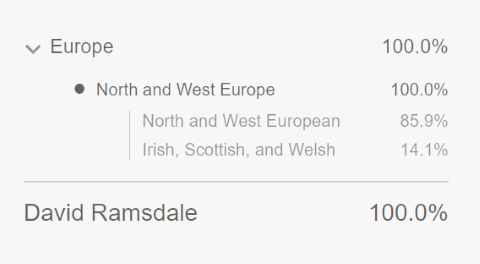

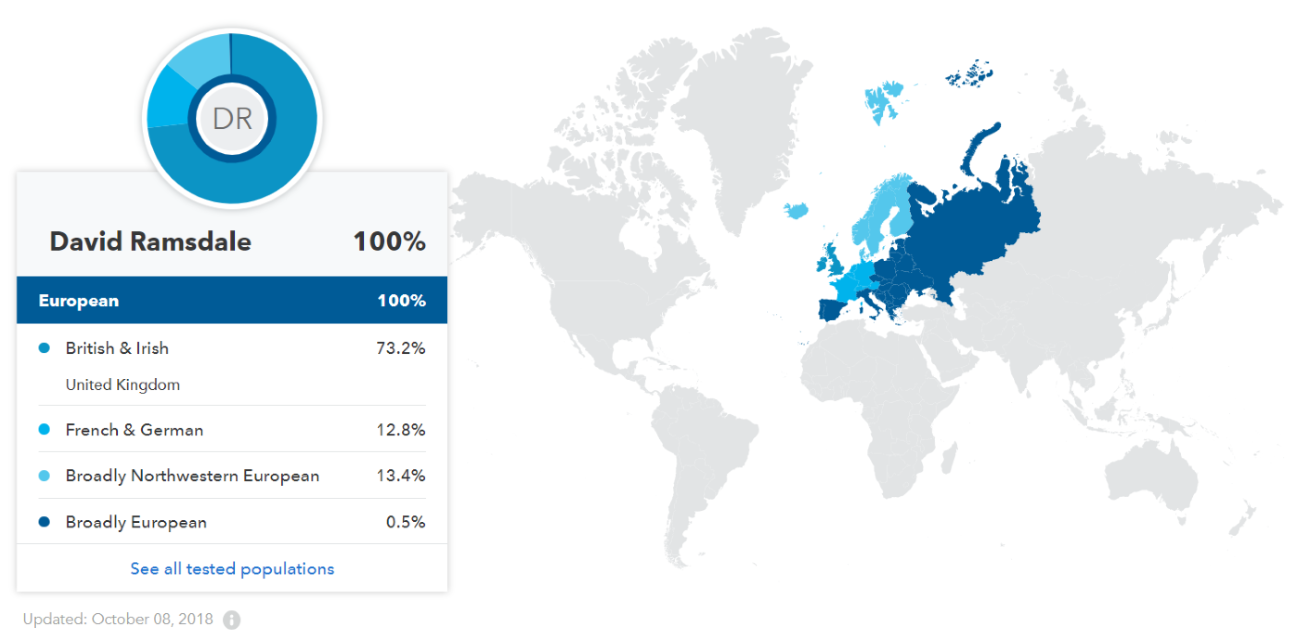

(above) DRR Ethnicity 8 October 2018 (23andme.com)

(above) DRR Ethnicity updated 14 October 2019 (23andme.com)

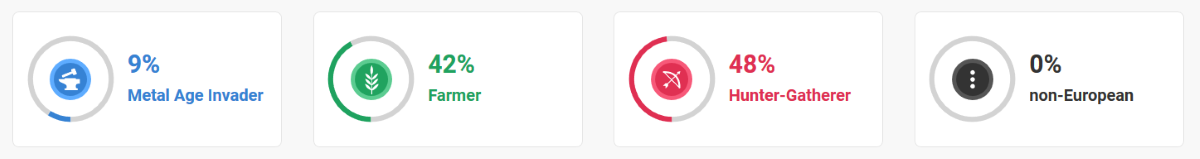

(above) DRR ancient European origins

The European continent has witnessed many episodes of human migration, some of which have spanned thousands of years. The most recent research into these ancient migrations on the European continent suggests that there were three major groups of people that have had a lasting effect on present day peoples of European descent: hunter-gatherers, early farmers, and metal age invaders. The image below displays the percentages of autosomal DNA that I still carry from these ancient european groups.

Metal Age Invader 9%

Following the Neolithic Era (New Stone Age), the Bronze Age (3,000 to 1,000 BCE) is defined by a further iteration in tool making technology. Improving on the stone tools from the Paleolithic and Neolithic Eras, tool makers of the early Bronze Age relied heavily on the use of copper tools, incorporating other metals such as bronze and tin later in the era. The third major wave of migration into the European continent is comprised of peoples from this Bronze Age; specifically, Nomadic herding cultures from the Eurasian steppes found north of the Black Sea. These migrants were closely related to the people of the Black Sea region known as the Yamnaya.

This migration of Bronze Age nomads into the temperate regions further west changed culture and life on the European continent in a multitude of ways. Not only did the people of the Yamnaya culture bring their domesticated horses, wheeled vehicles, and metal tools; they are also credited for delivering changes to the social and genetic makeup of the region. By 2,800 BCE, evidence of new Bronze Age cultures, such as the Bell Beaker and Corded Ware, were emerging throughout much of Western and Central Europe. In the East around the Urals, a group referred to as the Sintashta emerged, expanding east of the Caspian Sea bringing with them chariots and trained horses around 4,000 years ago.

These new cultures formed through admixture between the local European farming cultures and the newly arrived Yamnaya peoples. Research into the influence the Yamnaya culture had on the European continent has also challenged previously held linguistic theories of the origins of Indo-European language. Previous paradigms argued that the Indo-European languages originated from populations from Anatolia; however, present research into the Yamnaya cultures has caused a paradigm shift and linguists now claim the Indo-European languages are rooted with the Yamnaya peoples.

By the Bronze Age, the Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b was quickly gaining dominance in Western Europe (as we see today) with high frequencies of individuals belonging to the M269 subclade. Ancient DNA evidence supports the hypothesis that the R1b was introduced into mainland Europe by the Bronze Age invaders coming from the Black Sea region. Further DNA evidence suggests that a lactose tolerance originated from the Yamnaya or another closely tied steppe group. Current day populations in Northern Europe typically show a higher frequency of relatedness to Yamnaya populations, as well as earlier populations of Western European Hunter-Gatherer societies.

Farmer 42%

Roughly 8,000 to 7,000 years ago, after the last glaciation period (Ice Age), modern human farming populations began migrating into the European continent from the Near East. This migration marked the beginning of the Neolithic Era in Europe. The Neolithic Era, or New Stone Age, is aptly named as it followed the Paleolithic Era, or Old Stone Age. Tool makers during the Neolithic Era had improved on the rudimentary "standard" of tools found during the Paleolithic Era and were now creating specialized stone tools that even show evidence of having been polished and reworked. The Neolithic Era is unique in that it is the first era in which modern humans practiced a more sedentary lifestyle as their subsistence strategies relied more on stationary farming and pastoralism, further allowing for the emergence of artisan practices such as pottery making.

Farming communities are believed to have migrated into the European continent via routes along Anatolia, thereby following the temperate weather patterns of the Mediterranean. These farming groups are known to have populated areas that span from modern day Hungary, Germany, and west into Spain. Remains of the unique pottery styles and burial practices from these farming communities are found within these regions and can be attributed, in part, to artisans from the Funnel Beaker and Linear Pottery cultures. Ötzi (the Tyrolean Iceman), the well-preserved natural mummy that was found in the Alps on the Italian/Austrian border and who lived around 3,300 BCE, is even thought to have belonged to a farming culture similar to these. However, there was not enough evidence found with him to accurately suggest to which culture he may have belonged.

Although farming populations were dispersed across the European continent, they all show clear evidence of close genetic relatedness. Evidence suggests that these farming peoples did not yet carry a tolerance for lactose in high frequencies (as the Yamnaya peoples of the later Bronze Age did); however, they did carry a salivary amylase gene, which may have allowed them to break down starches more efficiently than their hunter-gatherer forebears. Further DNA analysis has found that the Y-chromosome haplogroup G2a and mitochondrial haplogroup N1a were frequently found within the European continent during the early Neolithic Era.

Hunter-Gatherer 48%

The climate during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 YA) fluctuated between episodes of glaciation (or ice ages) and episodes of warming, during which glaciers would retreat. It is within this epoch that modern humans migrated into the European continent at around 45,000 years ago. These Anatomically Modern Humans (AMH) were organized into bands whose subsistence strategy relied on gathering local resources as well as hunting large herd animals as they travelled along their migration routes. Thus these ancient peoples are referred to as Hunter-Gatherers. The timing of the AMH migration into Europe happens to correspond with a warming trend on the European continent, a time when glaciers retreated and large herd animals expanded into newly available grasslands.

Evidence of hunter-gatherer habitation has been found throughout the European continent from Spain at the La Brana cave to Loschbour, Luxembourg and Motala, Sweden. The individuals found at the Loschbour and Motala sites have mitochondrial U5 or U2 haplogroups, which is typical of Hunter-Gatherers in Europe and Y-chromosome haplogroup I. These findings suggest that these maternally and paternally inherited haplogroups, respectively, were present in the population before farming populations gained dominance in the area.

Based on the DNA evidence gathered from these three sites, scientists are able to identify surviving genetic similarities between current day Northern European populations and the first AMH Hunter-Gatherers in Europe. The signal of genetic sharing between present-day populations and early Hunter-Gatherers, however, begins to become fainter as one moves further south in Europe. The hunter-gatherer subsistence strategy dominated the landscape of the European continent for thousands of years until populations that relied on farming and animal husbandry migrated into the area during the middle to late Neolithic Era around 8,000 to 7,000 years ago.

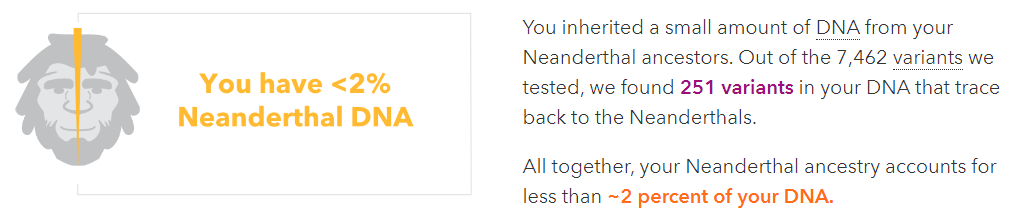

Neanderthal DNA ancestry

(above) Neanderthal DNA Ancestry (23andme.com)

More Neanderthal DNA (∼ 2%) than 68% of other 23andme customers. Neanderthals were prehistoric humans who interbred with modern humans before disappearing around 40,000 years ago.

5. livingdna.com DNA Test Results

DNA test results awaited (2 May 2020)

6. crigenetics.com DNA Test Results

DNA test results awaited (2 May 2020)

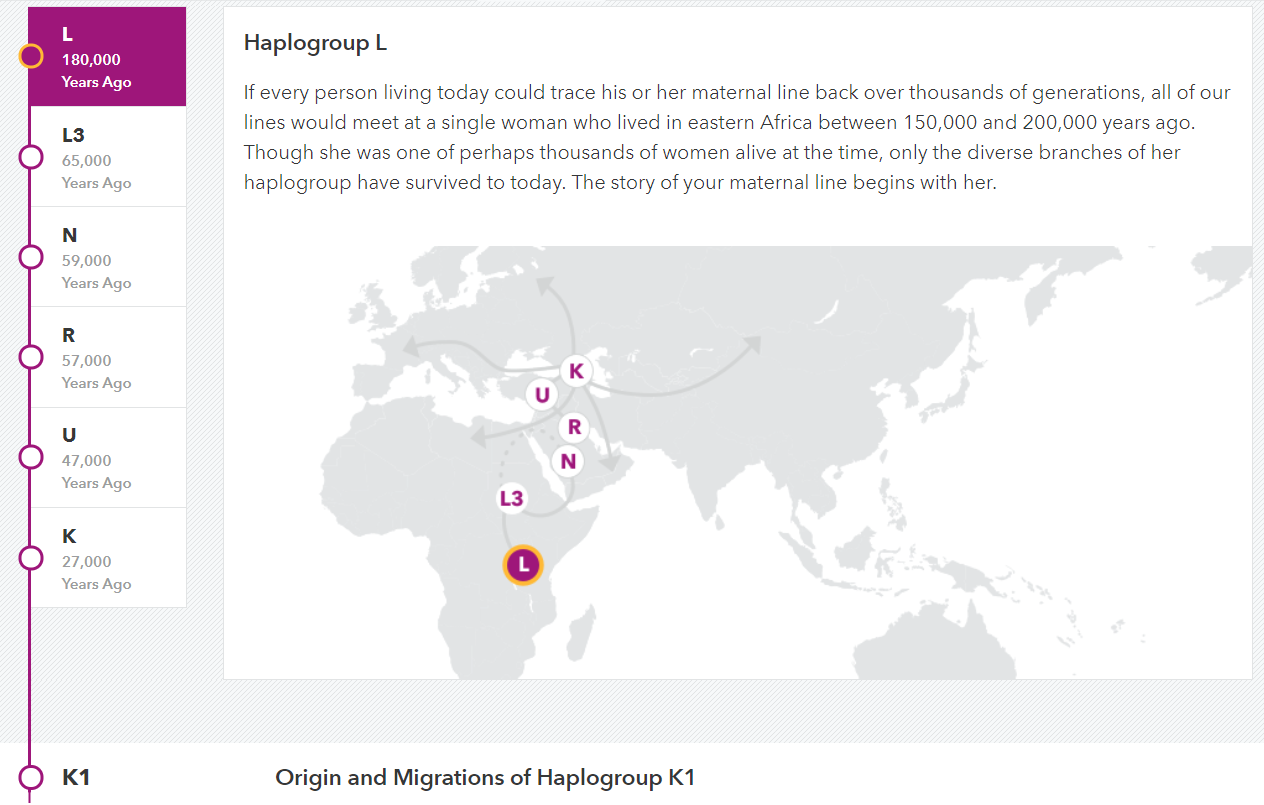

Maternal ancestry

(above) DRR maternal haplogroup migrations (23andme.com)

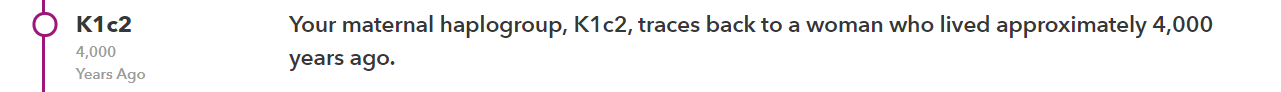

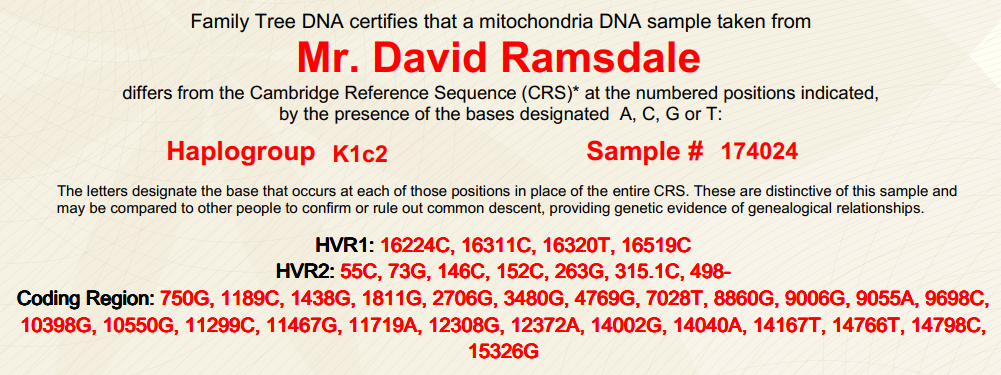

(above) DRR maternal haplogroup K1c2 (23andme.com and familytreedna.com)

Origin and Migrations of Haplogroup K1

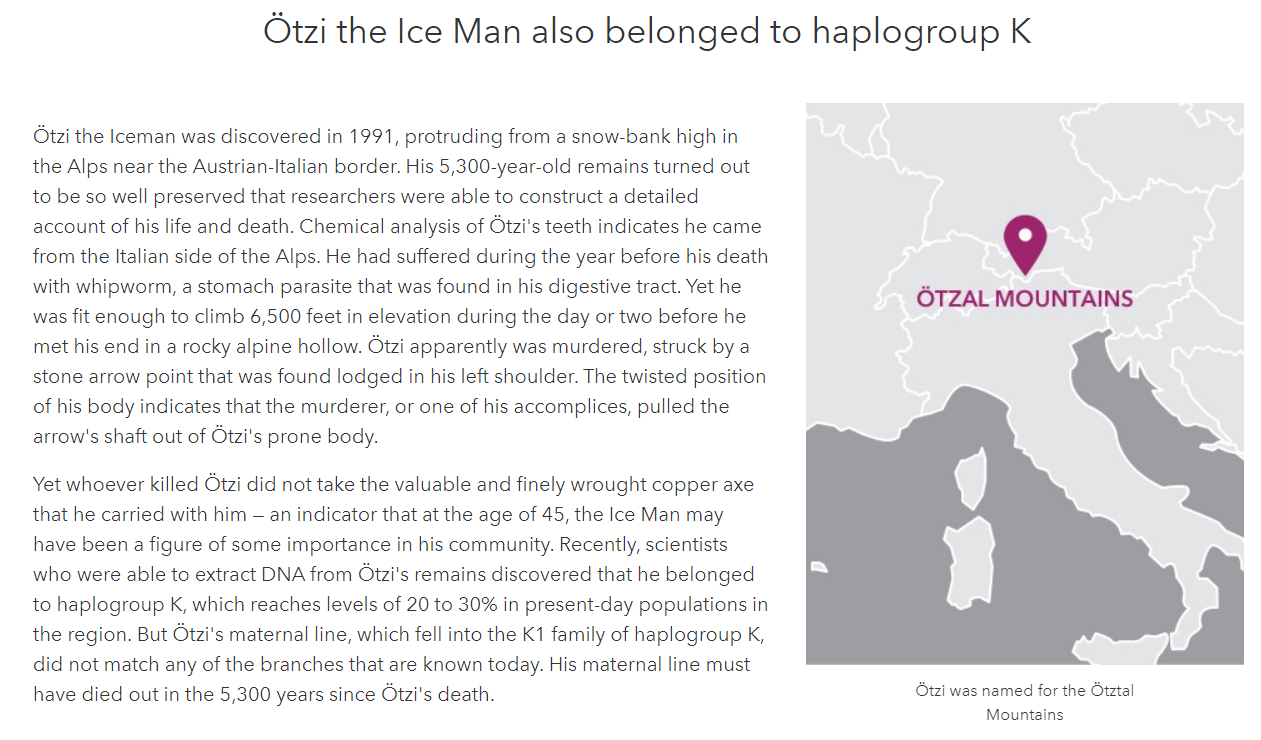

Haplogroup K1 is a relatively old branch of haplogroup K that traces back to a woman who lived approximately 22,000 years ago. She and her early descendants likely lived in the Middle East, where the K haplogroup traces its origins and continues to have a strong presence. Then, about 12,000 to 15,000 years ago, some women carrying K1 likely joined early migrations that moved west into Europe. The Ice Age was ending and temperate forests spread over the previously frigid continent. Human populations that had been blocked by massive ice sheets now expanded into the interior. Others came later, entering Europe with the spread of agriculture from the Middle East about 8,000 years ago. Today, members of K1 can be found throughout Europe, the Middle East, and even in Central Asia.

(above) Ötzi and Haplogroup K (23andme.com)

(above) DRR mtDNA HVR1 matches: 206 (familytreedna.com)

(above) DRR mtDNA Haplogroup K1c2 (familytreedna.com)

9. Genetic Ancestry Testing (articles)

"Population Replacement in Early Neolithic Britain", 18th February 2018, Selina Brace et al

Abstract

The roles of migration, admixture and acculturation in the European transition to farming have been debated for over 100 years. Genome-wide ancient DNA studies indicate predominantly Anatolian ancestry for continental Neolithic farmers, but also variable admixture with local Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. Neolithic cultures first appear in Britain circa 6000 years ago (kBP), a millennium after they appear in adjacent areas of northwestern continental Europe. However, the pattern and process of the British Neolithic transition remains unclear. We assembled genome-wide data from six Mesolithic and 67 Neolithic individuals found in Britain, dating from 10.5-4.5 kBP, a dataset that includes 22 newly reported individuals and the first genomic data from British Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. Our analyses reveals persistent genetic affinities between Mesolithic British and Western European hunter-gatherers over a period spanning Britain's separation from continental Europe. We find overwhelming support for agriculture being introduced by incoming continental farmers, with small and geographically structured levels of additional hunter-gatherer introgression. We find genetic affinity between British and Iberian Neolithic populations indicating that British Neolithic people derived much of their ancestry from Anatolian farmers who originally followed the Mediterranean route of dispersal and likely entered Britain from northwestern mainland Europe.

Discussion

The genomes of the six British Mesolithic individuals examined here appear to be typical of WHGs, indicating that this population spread to the furthest northwestern point of early Holocene Europe after moving from southeastern Europe, or further east, from approximately 14,000 years ago. It is notable that this genetic similarity among British Mesolithic and Loschbour individuals spans a period in Britain (circa 10.5-6 kBP) that includes the cultural transition to the Late Mesolithic, the potentially catastrophic Storegga landslide tsunami, and the separation of Britain from continental Europe as sea levels rose after the last ice age. This finding is inconsistent with the hypothesis of pre-circa 6 kBP gene flow into Britain from neighbouring farmers in continental Europe.

Our analyses indicate that the appearance of Neolithic practices and domesticates in Britain circa 6 kBP was mediated overwhelmingly by immigration of farmers from continental Europe, and strongly reject the hypothesised adoption of farming by indigenous hunter-gatherers as the main process. British farmers were substantially descended from Iberian Neolithic-related populations whose ancestors had expanded along a Mediterranean route, although our analyses cannot rule out the possibility that they also inherited a minority portion of their ancestry from the Danubian route expansion through Central Europe. Indeed, a recent study that investigated continental Neolithic farmer-related ancestry components in Neolithic Britain estimated ⅔ Mediterranean and ⅓ Danubian route, which may be consistent with the association between Britain's more easterly-distributed Carinated Bowl tradition and the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France, as Neolithic people in these regions of mainland Europe are thought to have interacted with populations of Central European Neolithic ancestry. The varied Neolithic cultures of northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands, the most likely continental sources for the British Neolithic, may represent a genetically heterogeneous population who shared large but variable proportions of their ancestry with Neolithic groups in Iberia via Atlantic and southern France.

Editor's note: Carinated Bowl - carinate is a shape in pottery defined by the joining of a rounded base to the sides of an inward sloping vessel. Made by some of the first people to settle and farm in the British Isles, carinated bowls were among the earliest known pots to be made in Britain and appeared around 6 kBP. Used by these Neolithic settlers to cook and store food, this style of pottery was one of the longest-lived styles to exist in Britain. Widely distributed across the British isles carinated bowls are characterised by their lack of decoration and their curved bases, which allow the pots to sit comfortably in the embers of an open fire, or upon any rough surface.

We caution that our results should not be interpreted as showing the Iberian Neolithic-related ancestry in British Neolithic people derives from migrants whose ancestors lived in Iberia, as we do not have ancient DNA data from yet unidentified source populations - possibly located in southern France - that were ancestral to both Iberian and British farmers. Available Middle Neolithic Iberian individuals are too late to represent the source population for early British farmers, and there is no archaeological evidence for direct immigration from Iberia. The lack of genome-wide data from Neolithic northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands means that it is not currently possible to identify proximal continental source populations.

The limited regional variation in WHG ancestry we see in the British Neolithic samples could reflect subtle but differing degrees of regional admixture between farmers and foragers, and/or multiple continental source populations carrying varying levels of WHG ancestry colonising different regions of Britain. What is clear is that across Britain all of our estimates for admixture between hunter-gatherers and farmers are very small, and that we find no evidence of WHG ancestry increasing as the British Neolithic progressed over time. In contrast, the resurgence of WHG ancestry in all available continental European Middle Neolithic samples, prior to the British Neolithic transition and including a population sample from southern France, means that the level of WHG ancestry we see in most British Neolithic farmers could be accounted for entirely in continental source populations.

Evidence for only low levels of WHG introgression among British Neolithic people is striking given the extensive and complex admixture processes inferred for continental Neolithic populations. Low levels of admixture between these two groups on the wavefront of farming advance in continental Europe have been attributed to the groups maintaining cultural and genetic boundaries for several centuries after initial contact. Similarly, isotopic and genetic data from the west coast of Scotland are consistent with the coexistence of genetically distinct hunter-fisher-gatherers and farmers, albeit for a maximum of few centuries. The resurgence in WHG ancestry after the initial phases of the Neolithic transition in continental Europe indicates that the two populations eventually mixed more extensively. However there is no evidence for a WHG resurgence in the British Neolithic up to the Chalcolithic population movements associated with the Beaker phenomenon (circa 4.5 kBP). This is consistent with the lack of evidence for Mesolithic cultural artefacts in Britain much beyond 6 kBP and with a major dietary shift at this time from marine to terrestrial resources; particularly apparent along the British Atlantic coas.

In summary, our results indicate that the progression of the Neolithic in Britain was unusual when compared to other previously studied European regions. Rather than reflecting the slow admixture processes that occurred between ANFs and local hunter-gatherer groups in areas of continental Europe, we infer a British Neolithic proceeding with little introgression from resident foragers - either during initial colonization phase, or throughout the Neolithic. This may reflect the fact that farming arrived in Britain a couple of thousand years later than it did in Europe. The farming population who arrived in Britain may have mastered more of the technologies needed to thrive in northern and western Europe than the farmers who had first expanded into these areas. A large-scale seaborne movement of established Neolithic groups leading to the rapid establishment of the first agrarian and pastoral economies across Britain, provides a plausible scenario for the scale of genetic and cultural change in Britain.

"One in 33 men can claim to be direct descendants from the Norse warriors", Daily Mail, 10th March 2014

Around 930,000 people can claim to be of direct Viking descent …

A study compared Y chromosome markers to estimated Viking DNA patterns …

The Viking DNA patterns are rarely found outside Scandinavia …

Almost one million Britons alive today are of Viking descent, which means one in 33 men can claim to be direct descendants of the Vikings. Around 930,000 descendents of warrior race exist today, despite the Norse warriors' British rule ending more than 900 years ago. A genetic study carried out by BritainsDNA compared the Y chromosome markers - DNA inherited from father to son - of more than 3,500 men to six DNA patterns that are rarely found outside of Scandinavia and are associated with the Norse Vikings.

Records estimate that the first Viking longships landed in Britain in 793 AD and that the Vikings went on to rule parts of England until the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Vikings left behind buildings, culture and words that are still used in the English language today. Key findings from the research include that men from the Shetland (29.2%) and Orkney (25.2%) Islands, heavily populated by the Northmen in the Viking Age, are most likely to have Viking in their bloodlines. South of Scotland Yorkshire (5.6%) and Northern England (4%) are the most prominent areas of the country for Norse Viking ancestry with more than 300,000 Northern men able to claim direct descent - accounting for almost a third of descendants.

Further south the percentage of Viking descendants drops significantly, with South West England home to as few as 40,000 father line descendants. Despite being a known hotspot for the Vikings when they first landed, Ireland has very little sign of a Norse genetic contribution today, with only 1.4% of men from the Emerald Isle thought to have Viking connections. Leinster has a lower count of Viking bloodlines than any other part of Britain or Ireland. Doctor Jim Wilson, chief scientist at BritainsDNA, said:

"Despite arriving well over 1,000 years ago the Viking legacy still remains strong in Britain and Ireland. The research suggests that the concentration of Norse blood is quite variable, but as the Y chromosome only relates to the nation's male population and only to one ancestral lineage for each man, there is a very real chance that many more of us are related to the Vikings."

Regions with highest percentage of Viking descendants:

- Shetland: 29.2%

- Orkney: 25.2%

- Caithness: 17.5%

- Isle of Man: 12.3%

- Western Isles: 11.3%

- North West Scotland and Inner Hebrides: 9.9%

- Argyll: 5.8%

- Yorkshire: 5.6%

- North East Scotland: 4.9%

- North England: 4%

- East England: 3.6%

- South West Scotland: 3.2%

- South East Scotland: 2.7%

- Central England: 2.6%

- Central Scotland: 2.2%

- South East England: 1.9%

- South West England: 1.6%

- Ireland (Ulster): 1.4%

- Ireland (Munster): 1.3%

- Ireland (Connacht): 1.2%

- Wales: 1%

- Ireland (Leinster): 1%

"To claim someone has 'Viking ancestors' is no better than astrology", Mark Thomas, The Guardian, Monday, 25th February 2013

Exaggerated claims from genetic ancestry testing companies undermine serious research into human genetic history.

You may have missed the latest genetic discovery. As reported by The Daily Telegraph on Friday: "One million British men may be directly descended from the Roman legions". The story reappeared on Sunday, at the Who Do You Think You Are - Live event at London's Olympia, when it was repeated by Alistair Moffatt, the managing director of BritainsDNA, the company behind the claims.

Such stories are becoming increasingly common in newspapers, on television and radio. Last week on the BBC miniseries Meet the Izzards we were told that Eddie Izzard is a Viking descendant on his mother's side and an Anglo-Saxon descendant on his father's. Last year The Observer reported that Tom Conti has Saracen origins and is a relative of Napoleon Bonaparte.

And for upwards of £150 you too can have your DNA "tested" by any of a number of direct-to-consumer ancestry companies. But how reliable are these claims? The truth is that there is usually little scientific substance to most of them and they are better thought of as genetic astrology.

For some time it has been possible to compare DNA sections among individuals; and in a broad sense greater genetic similarity means greater relatedness. But you have inherited different sections of your DNA from different ancestors, and as we look back through time the number of ancestors you have almost doubles with each generation (it would double exactly were it not for the fact that we are all somewhat inbred).

This means that you don't have to look very far back before you have more ancestors than sections of DNA, and that means you have ancestors from whom you have inherited no DNA. Added to this, humans have an undeniable fondness for moving and mating - in spite of ethnic, religious or national boundaries - so looking back through time your many ancestors will be spread out over an increasingly wide area. This means we don't have to look back much more than around 3,500 years before somebody lived who is the common ancestor of everybody alive today.

And perhaps most surprisingly, it has been reasonably estimated that around 5,000 years ago everybody who was alive was either the common ancestor of everybody alive today, or of nobody alive today; at this point in history we all share exactly the same set of ancestors.

What does this say about the descendants of the Roman legions ? It says almost everybody in Britain is one, as well as being the descendant of Vikings, Celts, Anglo-Saxons, Arabs, Jews, Saracens, Goths, Vandals, or whatever ethnic group you want to choose in Europe and its vicinity over the last few thousand years. Nobody is pure this, or pure that, and a substantial proportion of human ancestry is common to all of us. Ancestry is complicated and very messy.

Claims like those mentioned at the beginning of this article are usually based on only two sections of DNA: the mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited solely through the female line, and the male line equivalent, the Y chromosome. It is possible to compare these and make reasonable estimates of how long ago two individuals share a common ancestor through the male or female line, although such estimates are usually rather imprecise.

But saying where, and in what ethnic group, that common ancestor lived is considerably more speculative. In the hands of "genetic ancestry testing" companies this speculation almost invariably comes from the murky world of interpretative phylogeography - an approach to "reading" our genetic history that is easily steered by subjective biases, has never been scientifically shown to work and, in some forms, has been explicitly shown not to work.

So saying this or that Y chromosome came to Britain with the Roman legions, or that Oprah Winfrey has Zulu mitochondrial DNA, is just storytelling. Stories are fine if it is made clear that is all they are. But science isn't about telling stories, it's about testing them (in science we prefer the term hypothesis testing).

The simplicity of how Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA are inherited is part of their appeal in ancestry testing: you don't have to worry about that inconvenient doubling of your ancestors with each generation back in time. You only have one father, one father's father, etc.

But the price of that simplicity is irrelevance: those two lineages represent a rapidly diminishing fraction of your ancestry the further back in time you go. It may be the case that your mitochondrial DNA lineage came to Britain with the Vikings - although that would be extremely difficult to demonstrate scientifically - but if true, this would still say very little about your origins.

There are some situations where Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA information can be useful. It is, for example, reasonable to use large samples of these DNA types to say something about the histories of populations, if analyses are performed carefully and at the population level. Also, if genealogical research (parish records, surnames, etc.) suggests that two men share a common male line ancestor in the 16th century, the Y chromosome could be used to support or reject this claim. But individual Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA types provide no more than the vaguest hint about where their ancestors lived hundreds, or thousands of years ago.

So why do newspapers report these claims and why do TV and radio programme makers base documentaries on them ? After all, there are plenty of experts who are engaged in scientifically cautious research on our genetic history and will point out their absurdity. One reason is that, being simple "just so" stories, they have a popular appeal that cannot be matched by the more rigorous population level testing of migration histories. The bias is always towards the story rather than the science.

Another possible reason is that "ancestry testing" is aimed at individuals, although in reality the statements made are sufficiently general that they could be true for a large number of people. This is reminiscent of the "Forer effect" in psychology - the observation that individuals will tend to believe descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored specifically for them, but are in fact vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people. The same effect has been used to explain the popularity of horoscopes.

Yet another possible reason for the popularity of genetic ancestry stories is that because of the inherently random nature of the way genes are passed on to offspring, and mutation - the processes that generate genetic differences - very different population histories can give rise to the same patterns of genetic differences between individuals. This means that one set of genetic similarities cannot equate to only one possible history and we have no choice but to use statistical models. But statistical models give the sort of probabilistic answers that only statisticians find sexy.

"Genetic astrology" stories are often promoted by people with financial interests in genetic ancestry testing companies, those concerning "Roman legions" and "Meet the Izzards" being no exception. On 9th July 2012 Alistair Moffat - co-founder of the ancestry testing company BritainsDNA and Rector of St Andrews University - appeared on BBC Radio 4's Today Programme to make several claims about genetic ancestry that were wildly inaccurate, so that even his business partners, under pressure, eventually accepted that errors had been made.

My colleague Prof David Balding and I wrote to the BBC and to the two main scientists at BritainsDNA - both of whom we knew - expressing our concerns about the claims being made. Our expressions of concern over accuracy were met with threats of legal action for defamation by Mr Moffat's solicitors.

Perhaps it is harmless fun to speculate beyond the facts, armed with exciting new DNA technologies ? Not really. It costs unwitting customers of the genetic ancestry industry a substantial amount of hard-earned cash, and it disillusions them about science and scientists when they learn the truth, which is almost always disappointing relative to the story they were told.

Exaggerated claims from the consumer ancestry industry can also undermine the results of serious research about human genetic history, which is cautiously and slowly building up a clearer picture of the human past for all of us.

Many of the commercial companies plant stories in the media that sound exciting and seem scientific. But very often they are trivial or wrong, are not published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, and just serve as disguised PR for the company.

Mark Thomas is professor of evolutionary genetics at University College London

"If that's genetics, then I'm the Queen of Sheba, James Gillespie, The Sunday Times, 23rd December 2012

BBC Radio 4 is caught up in a row over its airing of 'dubious' science

When James Naughtie presented a gentle item on the Radio 4 Today programme (Monday, 9th July 2012 at 07:19) about tracing ancestors through DNA testing, it hardly seemed likely to cause a stir. Instead it has plunged the veteran broadcaster into a row involving warring academics and the Queen of Sheba.

In July, Naughtie interviewed his old friend Alistair Moffat, whose business interests include BritainsDNA, which traces the "deep ancestry" of individuals through a saliva test. The relationship between the two men was not revealed to listeners.

During the interview Moffat claimed his company had found that Marina Donald, 69, of Edinburgh was a descendant of the Queen of Sheba and that Ian Kinnaird, a retired lecturer living in the Highlands, was the first person in western Europe who could trace his descent directly from the first woman on earth: an "Eve" who lived 190,000 years ago.

"It's extraordinary, Jim," Moffat said on air. "What we have discovered is the Bible, the Old Testament, beginning to come alive."

The BritainsDNA finds may have gone largely unremarked (except in the columns of The Daily Telegraph and the Scottish edition of The Sunday Times) but they caused a stir among geneticists at University College London.

"Complete and utter nonsense," said David Balding, a professor of statistical genetics at the university's genetics institute. "We were shocked by the pathetic, lame interviewing [and the claims]."

Balding fired off a complaint to the BBC which responded:

"We interviewed Mr Moffat in good faith. It's fair to point out that the questioning was exploratory rather than directly challenging."

Balding added:

"I am appalled by how bad the interview was, but my complaint was dismissed so lightly. I made it clear I was a professor with relevant experience and they just dismissed it with no real argument at all. It was just a vacuous reply."

The row has featured on scientific websites. BritainsDNA employs geneticists to conduct the £170 DNA tests. Moffat himself is not a scientist but a writer and broadcaster. He gave his company website address during the broadcast. Balding maintains that the science available cannot back up the claims about the Queen of Sheba or Eve. "Absolutely not," he said.

"Most of this stuff is based on a tiny bit of evidence. Basically they found a genetic type that is now common in east Africa. The Queen of Sheba was in east Africa but she was there 3,000 years ago, so there's no basis for linking those two. That genetic type is common in east Africa and rare in Europe. But it still exists all over Europe so there's no reason to link it to the Queen of Sheba. It's just a story with a 1% overlap with the facts."

It is not the first time that Naughtie and Moffat have appeared together on the Today programme. They did an item last year in which DNA was used to suggest that Naughtie, a Scot, is really an Englishman.

Moffat's recent book carries an introduction by Naughtie and a YouTube video posted in October last year shows the BBC presenter endorsing Moffat's bid to become rector of St Andrews University. "He's a good guy, a fun guy," Naughtie says in the video, describing Moffat as "an old friend".

Moffat said yesterday:

"My appearance on the Today programme was not a personal favour or aimed at promoting the business. I was invited to discuss the science and history behind our work, which is what I did. What we do attracts huge interest and we have done items on many radio and TV programmes and have our work reported, including in The Sunday Times. We welcome debate. Dr Jim Wilson [the chief scientist at BritainsDNA] responded to the scientific points raised [by geneticists] at the time but has had little response. Our work is intended as a combination of history and genetics, using the one to inform the other. We believe that this is extremely worthwhile and not something to be undermined by ill-informed comment."

Yesterday the BBC and Naughtie were sent a series of questions. The only reply was:

"Alistair Moffat appeared on the Today programme to discuss the UK's genetic heritage. He was interviewed by Jim Naughtie as one of the presenters on the programme that morning and was questioned on the findings of his project."

There was no response to any of the criticisms levelled by the scientists.

In its response to Balding's complaint the BBC said:

"Today regularly interviews commercial firms about their products - the criterion we use is whether the story is interesting in its own right."

Contributors' summaries (20th December 2012):

"That really is outrageous. It's a blatant advert for the company of a friend presented uncritically as leading edge science. Even if Naughtie is gullible enough to believe this stuff, the editors should have stepped in with some real questions about evidence and peer acceptance and questioned the commercial aspect of the work. The BBC is not in a good place at the moment. They have been crucified by a parliamentary committee and their editorial standards have been called chaotic and totally inadequate. Yet no-one gets sacked - the worst of them get huge pay-offs at our expense. One wonders what interests lie behind many of the other questionable reports that crop up on BBC news. Shocking."

"I think this is one of the most shocking aspects of the story. Jim Naughtie has interviewed his friend Moffat more than once on BBC radio, without to my knowledge the friendship connection being mentioned. Moffat seems to have little relevant expertise, and has taken the opportunity to promote his business interests without making it clear that there was a business interest involved. From what I've heard, Naughtie has not asked his friend any kind of probing question, and no qualified scientist was invited to comment on Moffat's dubious claims. And when I complained to the BBC about this, the complaint was dismissed with no real response to the issues raised (I wasn't aware of the friendship at the time of the complaint)."

The rise and fall of BritainsDNA: a tale of misleading claims, media manipulation and threats to academic freedom : Genealogy, 2nd November 2018

Abstract: Direct-to-consumer genetic ancestry testing is a new and growing industry that has gained widespread media coverage and public interest. Its scientific base is in the fields of population and evolutionary genetics and it has benefitted considerably from recent advances in rapid and cost-effective DNA typing technologies. There is a considerable body of scientific literature on the use of genetic data to make inferences about human population history, although publications on inferring the ancestry of specific individuals are rarer. Population geneticists have questioned the scientific validity of some population history inference approaches, particularly those of a more interpretative nature. These controversies have spilled over into commercial genetic ancestry testing, with some companies making sensational claims about their products. One such company - BritainsDNA - made a number of dubious claims both directly to its customers and in the media. Here we outline our scientific concerns, document the exchanges between us, BritainsDNA and the BBC, and discuss the issues raised about media promotion of commercial enterprises, academic freedom of expression, science and pseudoscience and the genetic ancestry testing industry. We provide a detailed account of this case as a resource for historians and sociologists of science, and to shape public understanding, media reporting and scientific scrutiny of the commercial use of population and evolutionary genetics. View full text

- The Moffat/BritainsDNA saga : UCL Molecular and Cultural Evolution Lab

Blog 9th July 2012 to 3rd July 2017 - How I discovered I wasn't genetically Scottish by Alistair Moffat : BioNews

20th March 2011 - Buyer beware in ancestry testing! : Gene Expression

Pingback on 18th December 2012 at 06:34 - Abuses of genomic screening, advertising on the BBC and a shocking legal threat : DC's Improbable Science

Pingback on 20th December 2012 at 16:54 - BritainsDNA - Caveat Emptor | DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Pingback on 20th December 2012 at 17:42 - Mitochondrial Eve: a de facto deception ? : Gene Expression

Pingback on 4th January 2013 at 17:43 - Genealogy, DNA marketing, truth, and fiction in family history | Onward To Our Past

Pingback on 2nd March 2013 at 13:34 - Prince William may have little to no Indian ancestry : Gene Expression

Pingback on 14th June 2013 at 23:35 - You might be a Pict if … | DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Pingback on 24th August 2013 at 15:13 - "Scientism" and Ways Forward | merovingianworld

Pingback on 30th August 2013 at 11:11 - Exaggerations and errors in the promotion of genetic ancestry testing : Genomes Unzipped

17th December 2012

"Genetic Ancestry Testing" (7th March 2013), Sense about Science

Read our guide Sense About Genetic Ancestry Testing

Part of a rapidly growing market for genealogy, commercial 'genetic ancestry tests' offer people a profile of their genetic history based on a DNA sample for around £200. The test findings tell people that they have links to groups such as Aboriginals or Vikings, to particular migrations of people and sometimes to famous figures such as Napoleon or Cleopatra. But genetics researchers warn that such histories are either so general as to be personally meaningless or they are just speculation from thin evidence.

Our guide explains why DNA tests are used in population research and why they do not provide accurate information about an individual's ancestry:

- Our individual ancestry is much shallower than people might imagine - the best estimate is that the most recent person from whom everyone alive today is descended lived just 3,500 years ago.

- As we look back through time we quickly accumulate more ancestors than we have sections of DNA, which means we have ancestors from whom we have inherited no DNA.

- There are millions of possible 'stories' of your ancestry. To know whether any one of them is likely to be true, it would need to be tested statistically for its likelihood against other possibilities.

- The genetic ancestry business uses a phenomenon well-known in other areas such as horoscopes, where general information is interpreted as being more personal than it really is.

The proliferation of companies obtaining DNA data from people interested in ancestry or disease profiles has raised serious concerns about privacy and openness about the use of these data. These are described in an award winning article in Scientific American "23andMe is terrifying, but not for the reasons the FDA thinks: The genetic-testing company's real goal is to hoard your personal data".

Some comments from genetic scientists:

David Balding, Professor of Statistical Genetics, UCL Genetics Institute: "Be wary of news items about genetic history - that someone famous is related to the Queen of Sheba or a Roman soldier. Often these come from PR material provided by genetic testing companies and can be trivial, exaggerated or just plain wrong. Genetic relatedness isn't very meaningful beyond a handful of generations away, because the amount of DNA you share with a very distant relative is negligible compared with the huge amount of DNA we all share from our common ancestors."

Mark Thomas, Professor of Evolutionary Genetics, Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, UCL: "Ancestry is complicated and very messy. Genetics is even messier. The Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA contain little information about an individual's ancestry. The idea that we can read our ancestry directly from our genes is absurd. In recent months there has been a spate of newspaper, TV and radio stories about famous people being descended from other famous people, or cool groups like Vikings. But these claims are usually planted by the companies that provide these so-called tests and are not backed up by published scientific research. This is business, and the business is genetic astrology".

Professor Mark Jobling, Professor of Genetics, University of Leicester: "Over-interpretation is always a pitfall in studies of genetic history, and particularly so when the history is of individuals. Some suppliers of individualised tests have been guilty of telling punters what they want to hear, by spinning implausibly specific stories about ancestry, such as Viking or Celtic origins for their Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA. Information and demystification is clearly needed".

Tracey Brown, Director, Sense About Science: "Genetics researchers are telling us that you are better off digging around in your loft than doing a DNA ancestry test if you want to find out about your family tree. We tend to see DNA tests as providing specific personal information, because of their use in crime detection and medical diagnosis. The genetic ancestry business trades on this".

Steve Jones, Emeritus Professor of Human Genetics, Evolution & Environment, UCL: "On a long trudge through history - two parents, four grandparents, and so on - very soon everyone runs out of ancestors and has to share them. As a result, almost every Briton is a descendant of Viking hordes, Roman legions, African migrants, Indian Brahmins, or anyone else they fancy".

Lounes Chikhi, CNRS Senior Scientist (Directeur de Recherche) at the Evolution and Biological Diversity lab, Paul Sabatier University, Toulouse, France: "The interpretation of genetic data is already difficult where geneticists try to reconstruct aspects of our recent evolutionary history, and becomes desperately so when we try to do the same for specific individuals. Unfortunately, many claims made by ancestry companies are closer to ‘folk genetics' than real population genetics. Everybody wants to be related to Genghis Khan or the Vikings (well I actually don't). The good news is that they all probably are".

Mike Weale, Reader in Statistical Genetics, Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, KCL: "I know it's only a tiny part of my true ancestry, but I would still love to know whether my male line ancestors were Vikings, or Celts, or both, or neither. Or at least be reasonably certain. Same goes for my female line. It's a shame there's no valid way to do that".

"Sense About Genealogical DNA Testing", Debbie Kennett, 15th March 2013

The announcement of the publication of Sense About Science's new briefing on Sense About Genetic Ancestry Testing attracted substantial media coverage. However, some of the articles did not give the wider context which may have given the false impression that all DNA ancestry tests are "meaningless". This left some readers to wonder about the scientific credibility of the DNA testing used in the investigation of the presumed remains of Richard III or the tests taken by genealogists as part of their family history research. However, the briefing made it clear that "There are credible ways to use the genetic data from mtDNA or Y chromosomes in individual ancestry testing, such as to supplement independent, historical studies of genealogy". This combination of genealogical research with DNA testing is known as genetic genealogy, and is a more specific and rigorous application than the generalised 'deep' ancestry tests critiqued in Sense About Genetic Ancestry Testing.

There are three different types of DNA tests that are applicable for family history purposes:

- Y-chromosome DNA tests explore the direct paternal line and are typically interpreted within the context of a surname study.

- Mitochondrial DNA tests can be used for genealogical matching purposes on the direct maternal line.

- Autosomal DNA tests, which currently sequence up to one million markers, can be taken to find genetic matches with close relatives, and sometimes more distant cousins, on all the different lines, through both males and females.

Good genealogy research examines and assesses all available sources, and DNA testing is just one type of record that can be weighed up with all the other evidence before drawing any conclusions.

Such is the popularity of genealogical DNA testing that the largest collections of mtDNA sequences and Y-chromosome haplotypes are available not in scientific databases but in genetic genealogy databases. Deep-rooted pedigrees compiled by genealogists can be consulted to inform the interpretation of research findings from population genetics studies, and there is considerable scope for further collaboration between genetic genealogists and population geneticists.

A single DNA test on its own provides only a limited amount of information, and the greater value of a test lies in the comparison process. This has led to the growth of large genetic genealogy databases and a proliferation of volunteer-run DNA projects, many of which are studying surnames. Y-chromosome DNA testing can be used to establish whether or not two men with the same surname share a common ancestor within a genealogical timeframe. Y-DNA testing can also help to confirm relationships deduced from traditional genealogical research and to establish which variant spellings of a surname are related. Many such studies are being carried out by members of the Guild of One-Name Studies. Mitochondrial DNA tests can be taken to compare relationships on the direct maternal line. MtDNA testing was used in the case of Richard III, and the preliminary results provided strong support for the identity of the remains found in the Leicester car park. The DNA evidence alone does not prove the case, as many press reports suggested; it supports other evidence, and further DNA analysis is ongoing.

An autosomal DNA test can be taken to verify whether or not two people share the expected amount of DNA for the presumed relationship, and can be used, for example, to confirm that two people share the same grandfather or great-grandmother. DNA tests do not confirm specific relationships but instead rely on probabilities to estimate the likely range within which a common ancestor might have lived or, in the case of autosomal DNA tests, the degree of kinship between two people. The more markers that are compared the more secure the verification.

While most people wishing to research their family tree would in the first instance be best advised to "dig around in their loft" before purchasing a DNA test, for some people, such as adoptees, this is not an option. For males a Y-chromosome DNA test can provide clues to the person's biological surname. A growing number of adoptees, both male and female, are finding matches with close family members in the large commercial autosomal databases.

While the inferences drawn from deep ancestry DNA tests may sometimes be speculative or so generalised as to be meaningless, genealogical DNA tests can be used effectively and legitimately as an additional tool in family history research.

- King TE & Jobling MA "What's in a name? Y chromosomes, surnames and the genetic genealogy revolution", Trends in Genetics 2009 25;351-360.

- Congiu A, Anagnostou P, Milia N et al "Online databases for mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms in human populations", Journal of Anthropological Sciences 2012 90;1-15

- Larmuseau MHD, Van Geystelen A, van Oven M, and Decorte R "Genetic genealogy comes of age: perspectives on the use of deep-rooted pedigrees in human population genetics", American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2013 Feb 26 [Epub ahead of print]

- Details of the genealogical research and DNA testing used in the case of Richard III can be found on the University of Leicester's website. The detailed research will be submitted for publication to a scientific peer-reviewed journal when the ancient DNA analysis has been completed. See also John Ashdown-Hill, The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of his DNA, The History Press, 2013 edition.

- Huff CD, Witherspoon DJ, Simonson TS et al "Maximum-likelihood estimation of recent shared ancestry (ERSA)", Genome Research 2011 21:768-74

- Rincon P "Adoptees use DNA to find surnames" BBC News online, 18th June 2008

- "War baby searches for father" ABC News, 5th October 2012

- "Finding family" Case history published on 23andMe blog

- "23andMe's tools help solve ancestry mystery" 23andMe blog

- CeCe Moore "Adoptee reunites with birth family at 23andMe" Your Genetic Genealogist, 21st December 2011

"Sense About Genetic Ancestry Testing" (7th March 2013) Sense About Science

There are now many companies which offer to tell you about your ancestors from a DNA test. You send off a sample of your DNA and £100-200 ($150-300), and in return you receive a report. The results of these tests may find a connection with a well-known historical figure. They might tell you whether you are descended from groups such as Vikings or Zulus, where your ancient relatives came from or when they migrated.

Adverts for these tests give the impression that your results are unique and that the tests will tell you about your specific personal history. But the very same history that you receive could equally be given to thousands of other people. Conversely, the results from your DNA tests could be matched with all sorts of different stories to the one you are given.

It is well known that horoscopes use vague statements which recipients think are more tailored than they really are (referred to as the 'Forer effect'). Genetic ancestry tests do a similar thing, and many exaggerate far beyond the available evidence about human origins. You cannot look at DNA and read it like a book or a map of a journey. For the most part these tests cannot tell you the things they claim to - they are little more than genetic astrology.

What can we know about your personal ancestors by looking at your DNA ?

Not much. Genetic ancestry tests use some techniques that have been developed by researchers for studying differences in DNA across many groups of people. The things we know about genetic ancestry, almost without exception, are about the genetic history of whole populations.

Companies use techniques from this field and sell their findings to people who want to find out about their personal history The techniques were not designed for this. The information they give is not unique to any individual. While there are other, more specific flaws with these testing services, that fundamental point alone means that the very concept of individual genetic ancestry tests is unsound.

What is genetic ancestry testing ?

There are different types of test. All of them use a small sample of a person's DNA, usually taken from a mouthwash or a cheek swab, and compare sections of it to the DNA of others for whom we have information about ethnicity and geographic location. Different tests look at different parts of an individual's DNA:

- Y chromosome DNA (this is only found in men and is inherited along the male line)

- mitochondrial DNA, 'mtDNA' (this is found in men and women, inherited along the female line)

- autosomal DNA (this is 98% of your DNA and can come from any ancestor)

Each of us has just one ancestral lineage for mtDNA, and each man just one for Y chromosome DNA . These are inherited as a unit - so in ancestry terms they are passed on like a single gene. On the other hand autosomal DNA is made up of thousands of sections of DNA, each with its own history.

What do we mean when we talk about ancestors ?

The DNA ancestry tests appeal to our interest in our family trees. However, our DNA is not the story of our family tree. It is a mosaic of genetic sequences that have been inherited via many different ancestors. With every generation you (nearly) double your number of ancestors because every individual has two parents - going back just 10 generations (200-300 years) you are likely to have around a thousand ancestors. We don't have to look back very far in time before we each have more ancestors than we have sections of DNA, and this means we have ancestors from whom we have inherited no DNA.

When genetics researchers talk about common ancestry between people they usually mean that they are tracing the inheritance of particular sections of DNA or genes. And we know that different sections of our DNA have different patterns of genetic ancestry. This means that researchers can get very different estimates of how recently we share ancestors, depending on what they are looking at:

- Researchers look at mtDNA to follow ancestry passed along the female line. For mtDNA, everyone alive today shares a common ancestor who lived between 160,000 and 200,000 years ago.

- When researchers look at Y chromosome DNA to follow ancestry through the male line, the most recent estimate is of a common ancestor who lived between 240,000 and 580,000 years ago.

- If we look at sections of DNA from other parts of the genome (autosomal DNA), the date of a 'common ancestral section of DNA' (that is, a section of DNA that everyone alive today has inherited) varies from gene to gene, but has been estimated to average around 1 million years ago.

There are some things genetic ancestry tests can tell you quite accurately

There are credible ways to use the genetic data from mtDNA or Y chromosomes in individual ancestry testing, such as to supplement independent, historical studies of genealogy. If, for example, two men have identified - through historical research, possibly involving surnames - a common male line ancestor in the sixteenth century, it would be reasonable to use their Y chromosome data to test this. There are some ancestry testing companies that offer this service.

To answer a specific question about individual ancestry with any degree of confidence requires a combination of historical records and genetic information. If, however, you look for the most recent person that everyone alive today is descended from, the best current estimate is that the individual lived only 3,500 years ago - which is much more recently than you might imagine.

Can genetic ancestry testing tell you that you are related to a historical figure ?

A company might tell you that you are related to the Queen of Sheba or Napoleon. The short response to this is, yes, you probably are! We could say this for many people alive today in connection with many people from the past without having to do any genetic test at all. We are all related, it's a matter of degree. Not only is our common ancestor estimated to have lived 3,500 years ago, but reasonable estimates show that every individual alive around 5,000 years ago was either a common ancestor of everyone alive today, or of no one alive today. So at that point in the past we all have exactly the same set of ancestors.

If you are told that you are genetically related (share a genetic marker) to someone who lived a long time in the past, it may well be true but is not very meaningful. In reality, all share the vast majority of our DNA through remote common ancestors - and we may have little DNA that is directly inherited from an ancestor who lived even just a few generations ago.

Can genetic ancestry testing tell you that your ancestors came from a particular group of people or part of the world ?

Genetic ancestry testing presents a simplified view of the world where everyone belongs to a group with a label, such as 'Viking' or 'Zulu'. But people's genetics don't reflect discrete groups. Even strong cultural boundaries, such as between the Germanic and Romance language groups in Europe, do not have very noticeable genetic differences. The more remote and less-populated parts of the UK, such as the Scottish Highlands, do have some genetic differences from the bulk of the population, but they are not big. There is no such thing as a 'Scottish gene'. Instead groups show a story of gradual genetic change and mixing.