The modern European gene pool was formed when three ancient populations mixed within the last 7,000 years. Blue-eyed, swarthy hunters mingled with brown-eyed, pale skinned farmers as the latter swept into Europe from the Near East. But another, mysterious population with Siberian affinities also contributed to the genetic landscape of the continent. The findings are based on analysis of genomes from nine ancient Europeans.

Agriculture originated in the Near East - in modern Syria, Iraq and Israel - before expanding into Europe around 7,500 years ago. Multiple lines of evidence suggested this new way of life was spread by a wave of migrants, who interbred with the indigenous European hunter-gatherers they encountered on the way. But assumptions about European origins were based largely on the genetic patterns of living people. The science of analysing genomic DNA from ancient bones has put some of the prevailing theories to the test, throwing up a few surprises.

Genomic DNA contains the biochemical instructions for building a human, and resides within the nuclei of our cells. In the new paper, Prof David Reich from the Harvard Medical School and colleagues studied the genomes of seven hunter-gatherers from Scandinavia, one hunter whose remains were found in a cave in Luxembourg and an early farmer from Stuttgart, Germany.

The hunters arrived in Europe thousands of years before the advent of agriculture, hunkered down in southern refuges during the Ice Age and then expanded during a period called the Mesolithic, after the ice sheets had retreated from central and northern Europe. Their genetic profile is not a good match for any modern group of people, suggesting they were caught up in the farming wave of advance. However, their genes live on in modern Europeans, to a greater extent in the north-east than in the south.

The early farmer genome showed a completely different pattern, however. Her genetic profile was a good match for modern people in Sardinia, and was rather different from the indigenous hunters. But, puzzlingly, while the early farmers share genetic similarities with Near Eastern people at a global level, they are significantly different in other ways. Prof Reich suggests that more recent migrations in the farmers' "homeland" may have diluted their genetic signal in that region today:

"The only way we'll be able to prove this is by getting ancient DNA samples along the potential trail from the Near East to Europe … and seeing if they genetically match these predictions or if they're different. Maybe they're different - that would be extremely interesting."

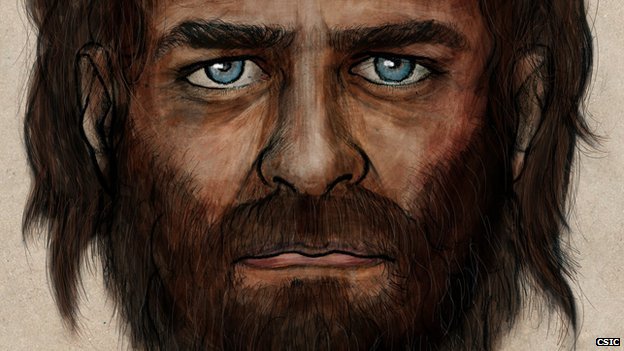

Pigmentation genes carried by the hunters and farmers showed that, while the dark hair, brown eyes and pale skin of the early farmer would look familiar to us, the hunter-gatherers would stand out if we saw them on a street today.

"It really does look like the indigenous West European hunter gatherers had this striking combination of dark skin and blue eyes that doesn't exist any more" Prof Reich said.

Dr Carles Lalueza-Fox, from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC - UPF) in Barcelona, Spain, who was not involved with the research, comments:

"If you look at all the reconstructions of Mesolithic people on the internet, they are always depicted as fair skinned. And the farmers are sometimes depicted as dark-skinned newcomers to Europe. This shows the opposite."

So where did fair pigmentation in present-day Europeans come from? The farmer seems to be on her way there, carrying a gene variant for light skin that's still around today.

"There's an evolutionary argument about this - that light skin in Europe is biologically advantageous for people who farm, because you need to make vitamin D" said David Reich. "Hunters and gatherers get vitamin D through their food - because animals have a lot of it. But once you're farming, you don't get a lot of it, and once you switch to agriculture, there's strong natural selection to lighten your skin so that when it's hit by sunlight you can synthesise vitamin D."

When the researchers looked at DNA from 2,345 present day people, they found that a third population was needed to capture the genetic complexity of modern Europeans. This additional "tribe" is the most enigmatic and, surprisingly, is related to Native Americans. Hints of this group surfaced in an analysis of European genomes two years ago. Dubbed Ancient North Eurasians, this group remained a "ghost population" until 2013, when scientists published the genome of a 24,000-year-old boy buried near Lake Baikal in Siberia. This individual had genetic similarities to both Europeans and indigenous Americans, suggesting he was part of a population that contributed to movements into the New World 15,000 years ago and Europe at a later date.

The ancient hunter from Luxembourg and the farmer from Germany show no signs of mixture from this population, implying this third ancestor was added to the continental mix after farming was already established in Europe.

The study also revealed that the early farmers and their European descendents can trace a large part of their ancestry to a previously unknown, even older lineage called Basal Eurasians. This group represents the earliest known population divergence among the humans who left Africa 60,000 years ago.