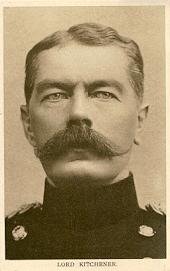

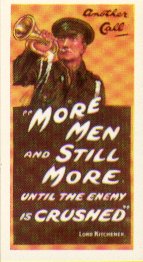

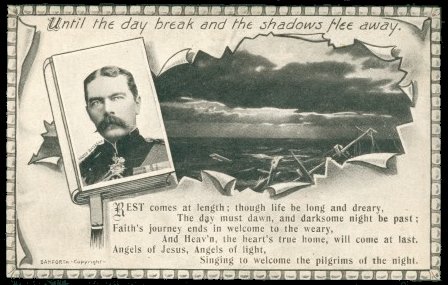

When war broke out on 4th August 1914 the Prime Minister, Mr. Asquith, was also acting as Secretary of State for War. On 6th August Lord Kitchener, on leave from Egypt where he was British agent, was appointed to this post. Immediately on assuming office he said that we must be prepared for a three years war and that we would require an army of seventy divisions.

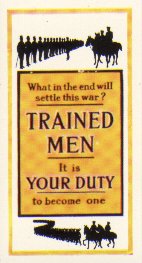

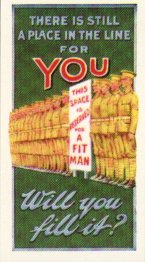

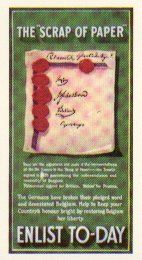

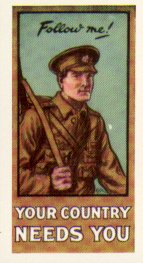

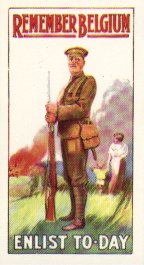

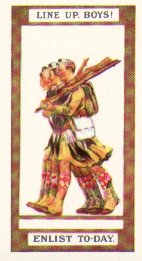

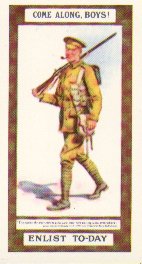

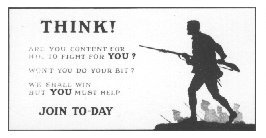

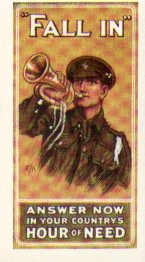

On 7th August a poster and notices in the newspapers called for an addition of 100,000 men, between 19 and 30, to the Army, serving for three years or the duration of the war. The response was overwhelming and within a few days the First Hundred Thousand had joined up and by the middle of September half a million men had enlisted. They included the best of their generation, eager to serve their country. Many gave their lives in the Somme battles of 1916 where the New Army battalions suffered grievous losses.

Kitchener decided that the massive expansion must be achieved by the creation of new armies separate from the Regulars and Territorials so he did not make use of the framework of the Territorial Force as envisaged in the Haldane plans.

The new army consisted of over 500 battalions (including the reserve units) and was popularly known at the time as Kitchener's Army. It was organised in thirty divisions formed in groups of six. The new battalions were raised as additional battalions of the regiments of Infantry of the Line sharing their traditions and regimental spirit. They were numbered consecutively after the existing battalions of their regiments and were distinguished by the word "Service" in brackets after the number.

Later Second Reserve and Local Reserve battalions were formed as explained below. A large number of new units were also raised for the Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers and other arms for the thirty new divisions. They did not, however, have the word "Service" in their titles.

There are five categories of New Army battalions:

- The service battalions raised in August and September 1914 formed the First (9th to 14th Divisions), Second (15th to 20th Divisions) and Third (21st to 26th Divisions). The three new armies were sometimes abbreviated to K1, K2 and K3. In addition to the twelve battalions for each division a number of Army Troops units were raised and attached to divisions for training. All these Army Troops battalions eventually went to regular or new army divisions. The 37th Division was formed in 1915 with thirteen Army Troops battalions.

- Another series of service battalions was formed in the autumn of 1914 with men from the reserve and extra reserve battalions, which were now well over establishment, to form the original Fourth Army (30th to 35th Divisions) known as K4. Later in order to provide reinforcements for the first eighteen divisions it was decided in April, 1915 to break up the divisions of the Fourth New Army and reconstitute the infantry as reserve battalions to train recruits and send drafts to the first three new armies. (The battalions became second reserve battalions and were organised in eighteen reserve infantry brigades. On 1st September 1916 all these second reserve battalions were absorbed in the Training Reserve.

- At the same time as the units of the first four armies were being formed a number of service battalions were being raised by committees from cities, towns, organisations and individuals. These battalions were clothed, housed and fed by these committees until the War Office took them over in 1915 and refunded the raisers' expenditure. These battalions supplied most of the infantry for the 30th to 41st Divisions. The new Fourth New Army divisions took over their numbers, 30th to 35th, from the original Fourth Army (see 2 above). The Fifth New Army (36th to 41st Divisions) included the 36th (Ulster) and 38th (Welsh) Divisions which were raised in Northern Ireland and Wales. The locally raised battalions had an additional title in brackets showing their connection with the district or organisation which helped to form them.

- The locally raised service battalions formed depot companies and in 1915 these companies were grouped to form local reserve battalions, with numbers following the parent battalions, to supply reinforcements to their service battalions. On 1st September 1916 these battalions were absorbed in the Training Reserve.

- A few more service and reserve battalions were formed in 1915 and 1916 in addition to those in the above four categories.

In the summer of 1918 about twenty garrison and other battalions were renamed service battalions. They were used to supply some of the infantry for the reconstitution of the 14th, 16th, 40th and 59th Divisions in France, which had been reduced to cadre after heavy casualties in the German offensives. These battalions had no connection with the service battalions of the New Army formed in the early years of the war.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry" (1970) R. F. K. Goldsmith (Leo Cooper, London) at pages 91 to 95

Chapter 7 The First World War

During the summer of 1915 the first of the 'New Army' divisions began to arrive in France. They were the cream of the nation, but the manner of their formation had deprived the Territorial Force of its intended role as the country's second line of defence. The Secretary-of-State for War, Lord Kitchener, having spent nearly all his service overseas, was not in touch with all that had been done of late to prepare the nation for war. He equated the Territorials with a class of French reservist of the same name that had made a far from favourable impression on him during the Franco-Prussian War. The prejudice stuck and the Territorials were by-passed as the main basis for the expansion of the army.

Amongst the early arrivals were the 6th and 7th DCLI. They were attached respectively to the First and Second to learn the peculiarities of trench warfare and they took their place in the line directly afterwards. The 8th DCLI followed a month or two later. The Regiment now had five battalions in France and nothing better illustrates the dimensions of the conflict than their casualties. In the wars that have so far entered our story, a regiment or battalion was thought to be hard hit if it suffered perhaps 200 casualties in a single engagement or twice that number in the course of a year's campaigning. Partly, of course, this was due to the difficulty of replacing casualties (and perhaps an efficient reinforcement system is not an unmitigated blessing). In 1915 a battalion was considered fortunate if it suffered fewer than a hunched casualties a month even in a quiet sector, and when the fighting flared up it could lose that number in a matter of hours. The Sixth had early experience of this for within a few weeks of their first spell in the trenches they were the object of a concentrated German attack that lasted two days and nights. They did not yield a yard of ground but it cost them over two hundred killed and wounded.

Towards the end of 1915 the Second and Eighth were switched with their divisions to Salonika and remained there for the rest of the war. The presence of Allied troops in Greece had more political than military significance. It was intended as a means of influencing Greece, still trying to preserve a precarious neutrality, and of bringing succour to Serbia. Of all side-campaigns it was the least productive - the Germans were justified in calling it the greatest Allied internment camp. None of this was the fault of the Second and Eighth and for three long years they successfully retained their spirit under conditions which were as trying, if less lethal, than those of the Western Front. The official enemy was the Bulgar, but the majority of casualties were caused by the mosquito.

Those who in 1914 joined the army with a view to seeing something of the world outside Europe, would have had to join the Territorials. Soon after the outbreak of war the 4th and 5th DCLI were duplicated. The 1/5th in due course was sent to France as a pioneer battalion and swallowed its twin in the process; the 1/4th and 2/4th both went to India towards the end of 1914 to release regular units there for active service. The 2/4th remained there for the duration, but the 1/4th moved to Aden in 1916 where British troops were confronting the Turks. In 1917 the battalion moved to Egypt and took part in Allenby's advance into Palestine, playing a major role during the battle of Nebi Samwil, which opened the way to the capture of Jerusalem.

Except for a few months during the winter of 1917-18 when the First were in Italy, the Western Front claimed the remaining effort of the regiment, reinforced in mid-1916 by the loth Battalion which, like the Fifth, were pioneers. It should not be thought that these pioneer battalions were in any sense lesser mortals than their brothers. First and foremost they were infantrymen. Although their task was primarily to maintain communications and defences, it was nearly always in the forward areas that they had to operate, very often under fire. They suffered their full toll of casualties and were always liable to be called on in an emergency to take their part in the fighting. The Fifth received a mention in despatches for a successful counter-attack near Ham when the Germans broke through on the Somme in March 1918, and a company of the Tenth helped to save a desperate situation at Delville Wood during the Battle of the Somme. Sometimes, too, the pioneers had to perform sapper tasks, as on the Escaut Canal in October 1918 when the Tenth rebuilt an entire pontoon bridge without assistance.

From 1916 onwards the fighting on the Western Front was on too large and general a scale for the actions of individual battalions to have much significance in a chronicle such as this. The First, Sixth, Seventh and Tenth took part in the Battle of the Somme (where the Sixth suffered over 30o casualties at Delville Wood in August and as many again in September at Courcelette). The First, Sixth, and Tenth were involved in the Battle of Arras in 1917, and the First, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh were all at Passchendaele. The Seventh, and Tenth were both in the great tank battle at Cambrai towards the end of 1917 and when the Germans broke through on the Somme the following March the Seventh, and Tenth were among the units thrown into the breach.

So it went on to the end, each battalion giving of its bravest and best whenever the call came. The Regimental Roll of Honour in the Great War of 1914-1918 contains over four thousand names, and the Memorial that stands outside the Keep at Bodmin is not without its meaning today, nor ever will be.